Melting Pot

Marianna Martin on Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle

In 2004, American identity is a complicated thing, despite what some of those espousing sides of the ideological arguments at stake in this election year may insist to the contrary. Is it necessarily the case that if you check off one set of identity “boxes” you belong to party A, and if you check off the other boxes, you belong to Party B? Identity takes all tenses—who people are, who people were, and whom they might become, and Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle supports the idea that the realities of the three might overlap a bit at all times to define who we are. Maybe America’s “melting pot” is no longer an external societal condition but something that can be wholly internalized in each individual’s conception of self.

The predictable debate supplied by reviewers of the latest release “from the director who brought you Dude, Where’s My Car?” this July centered around asking the real Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle to please stand up: Was the film’s true identity closer to the realm of the puerile stoner film? Or is Harold & Kumar a groundbreaking moment in American pop culture cum identity politics? A remarkable amount seemed to be at stake in considering the ramifications of this fast-food film even before its release, and the question that seemed to be on the audience’s minds as we waited for tickets to an advance screening at an urban university was one fraught with such weighty concerns: was the film a radical statement of ethnic inclusion in American youth culture cloaked in gross-out pratfalls, or was it another lowbrow commercial spectacle that had been window-dressed with a little “color” for novelty’s sake, like so many other exploitation films? The majority South Asian and East Asian audience seemed willing to risk the disappointment of the latter possibility, the college student ahead of me in line probably putting it most eloquently to a friend waiting with him: “Dude, how often do we get to see guys like us as the main guys in anything?”

A good question, and from a cheery, All-American frat boy type that’s well-represented on his campus. This dude just happened to be South Asian. Which brings us to confronting the idea that a little duality in this film is not only conceivable but a pretty good outcome if achieved. Harold & Kumar features likable minority protagonists with fully developed, stereotype-defying, well rounded personalities and is also an enormously silly film, ultimately a series of juvenile set pieces selected for their ability to keep the audience giggling through sheer quantity over originality. But because of the formulaic approach to plot (or an approximation of one) and faithful devotion to conventions of genre, the film manages to deliver only what is promised in the title. Harold and Kumar do indeed make it to White Castle, and dozens of greasy patties of dubious origin are only their most literal reward: Harold and Kumar have also breached the previously impregnable walls of the stoner genre and made a cinematic world traditionally populated by the dumb white male a comfortable home for themselves onscreen.

If Harold & Kumar hadn’t been played for a series of dumb and occasionally disgusting laughs, no new ground would have been broken—the “social issue film” is already an established genre that gets its own chapter in some undergraduate film textbooks. Instead, Harold and Kumar put a new face on stoner humor, which has been enjoying a revival in current popular media, with of course, Dude, Where’s My Car? and the Fox sitcom that launched Dude’s star, Ashton Kutcher, That 70s Show. Comedies based around bored suburban kids doing dumb things sober or altered are nothing new to American popular culture, but with the American Pie franchise and a plethora of other teen exploitation comedies, this August’s Without a Paddle being the latest entry of dim, privileged Anglo males screwing up for our laughs (in a truly perverse mood I might classify Fahrenheit 9/11 in this category too, if it weren’t so depressing and horrifying all the same) the cinematic image of the regular stoner has been realigned from its seventies associations with bucking the oppressive system to being one of the many privileges enjoyed by those who stand to reap the most from such a system. The kids in these more recent films are tuning out hard—without much attention paid to what they’re tuning out from—simply because they can do so without dire consequences. Part of the seventies drug culture was about rejecting a set of values that marginalized you, and if the stoners in seventies films were largely dropouts from the mainstream culture, with little to offer, the sense was that extraordinary things were required to avoid such marginalization, and acceptance by so flawed a system was little incentive for the less than exceptional to strive for better.

Cheech and Chong films of the seventies arguably introduced an ethnic slant to the image of drug use and dazed behavior played to comic cinematic effect, and their names are of course virtually synonymous with the idea of movies with stoner protagonists—to a degree that the casting of Tommy Chong as the middle-aged burnout Leo on That 70s Show is an inside joke in of itself before he ever speaks a word onscreen—but their screen identities are tied up in a tangle of politico-cultural issues specific to the seventies. It’s stretching things to claim that youth identity in popular culture at that time is the same animal as it is now. The distinction between popular culture and counterculture was a serious factor then, and one that there is no easy analogy for in the contemporary youth culture of this decade. Though Cheech and Chong–style stoners belong to the counterculture of the seventies, Dude’s stoners are part of today’s pop mainstream. Membership in the stoner group is not synonymous with membership in popular cultural identity today, but it’s no longer a strictly exclusionary factor either.

What’s curious about Harold and Kumar in comparison to Cheech and Chong is that this temporal shift in stoner popular identity allows them, though they are identifiably minority players like those predecessors, to be seated firmly in the contemporary mainstream along with their Anglo counterparts as well. They are provisionally and potentially marginalized by their ethnic identities, but for them, toking is a way of opting in and identifying with the mainstream, rather than a way of drifting further out. These are young men who, though they are aware of the obstacles their ethnicity can create in dealing with their Anglo peers, fully share in the same popular culture with those peers. Both of them are anxious to avoid any hint of conformity to the stereotypes through which they know others filter their interactions with them, and this is where the movie has some of its most ebullient and occasionally risky fun. The bits borrowed from other genre films are played as conscious set pieces, the clichés and stereotypes inherent to them turned up to full volume, and thus often resulting in bizarre twists on the old standards. A pair of horny, British twin girls on the Princeton campus invite the guys back to their dorm rooms: pursuing this ultimately dead end means Harold and Kumar miss out on a party thrown by the Korean Students association that, when glimpsed as they flee the campus, looks like a hedonistic club-raver’s dream and not the geekfest Harold was dreading, (lapsing for a moment himself into stereotypical assumptions about his own group). All encounters with exclusively white law enforcement take on surrealistic and grotesque forms due to the uniformly exaggerated racism of the cops, which is so far beyond the expectations of the protagonists as to be incomprehensible even to them.

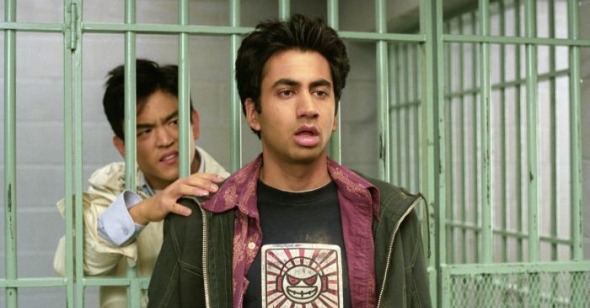

Two of the more daring scenarios involve both amusing and sympathetic twists on the “issue film” yet—played for laughs . . . mostly. Secure in their identities as cool American youths, they identify another South Asian and East Asian pairing of guys they see from their car as being “like the lame version of us.” Almost as soon as they say this, a white gang jumps the pedestrian pair and starts beating them. The surrealism of this moment, and Harold and Kumar’s incredulity as their laughs go sour, keep the scene surprisingly light given the inflammatory nature of the content. Later, when they leave the scene of another gang harassing a lone South Asian convenience store clerk, there’s a curious simultaneity of the situations’ unfairness, the knowledge that these are individual fights they have no hope of winning and they’re better off not involved in. But perhaps the most daring flaunting of expectation comes at the beginning of the film, when Kal Penn’s charismatic Kumar bombs his medical school interview by interrupting his older white male interviewer (Fred Willard) to take a cell phone call from Harold to discuss drug-related plans for that evening. But surely it will turn out Kumar was doomed to disappoint his father’s medical school hopes for him anyway, being a stoner and all? An emphatic “no,” we discover—busting a generic stereotype wide open. It turns out you can have a perfect MCAT score and not give a rat’s arse about it, and in fact be no less intelligent for your lifestyle choice. Kumar may make some dubious choices, but it’s not for lack of smarts. And this is perhaps where the stoner identity is redefined the most radically: the notion the stoner can hold multiple identities simultaneously, some of them beyond the stereotypical bounds of that choice.

The suggestion of this multiplicity is, I would argue, Harold & Kumar’s most innovative message about what identity means to young Americans. This film not only suggests what audiences are already supposed to know (though how easily it seems to be forgotten, John Cho and Kal Penn are both coming from previous roles as fairly mono-dimensional minority sidekicks in American Pie and Van Wilder, respectively), that minority personages don’t have to be walking embodiments of cultural stereotypes, but additionally dares to suggest that none of us have to be walking embodiments of any of our respective groupings either. It’s weirdly liberating to watch the silly glee with which Doogie Howser himself, Neil Patrick Harris, throws himself into his self-cameo, licking the seats of Harold’s car in a drugged, horny frenzy. The way that the stereotypes are amplified until they explode plays up the idea that hewing too closely to any one identity is inherently false, and that all of us are potentially multidimensional: more, there may be surprises in the secret, ancillary identities we carry around with us: once the holy grail of White Castle burgers has been found, Kumar gets philosophical and decides he might actually want to go to medical school after all, surprising not only Harold but himself.

This however, does not represent a sudden, absolute conversion to the straight and narrow—though the impulse is genuine, he’s soon distracted by an equally strong impulse to take a trip to Amsterdam, to enjoy some activities that are legal there and don’t count towards a medical degree. Kumar isn’t unwilling, in the end, to take on the career his father wants for him, it’s just that he doesn’t want to conform to his dad’s expectations of him precisely, because it limits the individuality of his identity. Harold, meanwhile, really is a conscientious worker at his job, and he really, sincerely, wants to do his job well. He’s sick of his coworkers taking advantage of his work ethic and allowing themselves to believe that he must be one of those hardworking Asians whose whole life is work, but Harold’s rejection of that stereotype doesn’t mean that he’s the opposite either—after all, wouldn’t that just be another flat, clichéd extreme?