Capital Punishment

Joanne Kouyoumjian on Salesman

One of the most remarkable things about the Right in American politics is its skill at conflating religious rhetoric with capitalist ideals. They’re selling a polemic, a good vs. evil view of the world in which unfettered greed and consumption is of service to the common good. All who stand in the way of the expansion of possible target markets are aligned with the devil himself. Capital is sacred, and those who interfere with our predestined, evangelical role of spreading the good news must be converted. This concept of conversion or death makes sense—it’s far better to create more consumers than it is to commit genocide. The new beast envelops all that it can in its path, perfecting the European expansionist model that has been in the works since the Crusades, and falsely parading under the banner of Christianity.

Salesman is Albert and David Maysles’ artful, direct cinema documentary about the way these ideas play out in everyday life—borrowing on credit is just as sacred an activity as reading scripture. Made in the mid-sixties, it is an unblinking observation of the journeys of four door-to-door bible salesmen in a somewhat less fearful time when people allowed strangers to enter their living rooms. It gives us unique access to American public and private spaces alike as they peddle their sacred wares to housewives in rollers, nervously chain-smoking cigarettes and wondering how they will be able to afford the enormous $40 volume before them, complete with full-color illustrations of the stations of the cross.

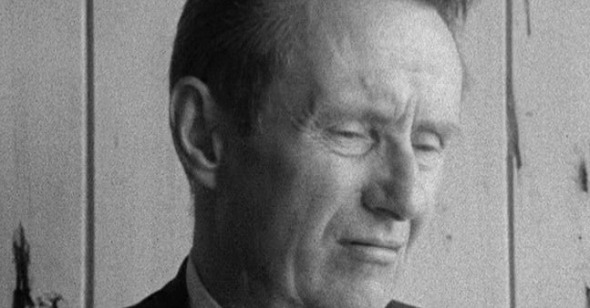

The film opens with an unconvincingly delivered pitch from Paul Bremmer, a somewhat unsuccessful bible salesman who is having doubts about his profession: “The Bible is the best selling book of all time.”

Nicknamed “The Badger,” Paul rushes through his pitch, telling his skeptical prospective customer that they need this Bible to truly enjoy what is certainly the best piece of literature known to mankind. Here the Bible is demoted to a cross between best-selling paperback and handsome leather-bound encyclopedia destined to sit undisturbed on a dusty shelf. This is a specifically American concept, as nowhere else in the Christian world do people take this attitude towards a religious text. Thus the text becomes object; there is nothing beyond the surface because it loses its spirituality when so easily commodified. Similarly, in most of the western world today, Christianity is not used to justify the use of unprovoked military force, and the concept of blind faith is not applied to elected leaders posing themselves as messianic saviors. Similarly, the absurdity of pitching a “Catholic Honor System Payment Plan” is a uniquely American one. Nowhere else does the sacred serve to justify consumption so utterly seamlessly.

Post-9/11, Bush made a plea to the American public to go out and spend money, that consumption was our patriotic duty. Likewise, in Salesman, the consumers are made to feel guilty about not wanting to purchase a Bible, almost as if it’s their duty as Christians to buy. In a particularly nasty display, the salesmens’ regional manager demonstrates how one can convince a prospective buyer that it’s his duty to purchase this Bible and then use it to convert his non-Catholic spouse to the faith.

Even more important than the American duty to consume as much as possible is our duty to make as much money as possible. This is most poignantly displayed during a sequence at a mandatory Bible salesman convention. In it, the manager behind the podium plays “Bad Cop” with his employees, threatening them with stories of other salesmen he’d recently terminated due to poor performance. Paul Bremmer is visibly uneasy and distracted as the man at the podium bellows out:

“Bible-selling is a good business…whoever isn’t making money, it’s their own fault.”

This is the illusion of self-reliance that seems easiest for the wealthy to dispense to those born into the life of indentured slavery. Guilt is a powerful tool, and feeling that poverty is a personal responsibility is just as powerful an opiate as the images of unbridled hedonistic consumption that are dangled before the eyes of a hypnotized nation. This consumption and the quest for the holy dollar that enables it are considered healthy forms of individualism, entrepreneurship, the American dream of the snake-oil salesman. Guilt and this objectivist “individualism” work hand in hand, a machine that insures our eternal servitude as long as we don’t question the source of such “common sense.”

Salesman shows us the hollowness of this aspect of American life, the endless road, the view from behind a steering wheel, anonymous hotel rooms in Boca Raton with faux Mediterranean décor, and entire planned communities with streets named after characters from 1001 Nights. Paul Bremmer uneasily navigates through this world of cheap illusion, unable to peddle Bibles because his pitch isn’t even convincing enough for himself. While his coworkers triumphantly compare sales, play poker and go for midnight swims in motel swimming pools, he remains pensive and quiet.

Bremmer is an excellent choice for a protagonist, precisely because his silences are often as telling as his words. The Maysles aren’t afraid to linger on Paul in real time as he wordlessly gazes out of the window of a train or a café at some unknown point in his memory over a half full cup of coffee and a cigarette. He often breaks his silences to tell a few sardonic jokes about his bad luck with sales or to imitate his father’s thick Cork accent. He ruminates about having to share a tuxedo with his older brother because his family couldn’t afford to have two. We know little about his past besides this story that he recounts and his imitations of his father. In this, Paul Bremmer partakes in that American nostalgia for the pastoral, the innocent, the “shire” of Cork or the poverty of working-class Boston. It’s almost as though we believe our society is caught up in some kind of unstoppable gravitation towards more consumption, more production, more alienation. It’s an exhausting concept to face and a seemingly insurmountable task to stop this machine that devours all in its path. How can one resist that which consumes and incorporates every attempt at a life beyond immediate gratification . . . do I daresay a spiritual life?

If the scripture of one of the world’s most widespread faiths and the basis of modern western culture can be packaged and sold door to door in this manner, if even the Bible which has been sacred for nearly 2,000 years can suddenly become incorporated into the dazzling system of objects, how can we alone resist?

The Maysles ask that question not with words but with poetry, moments uncovered with patience, observation, and Charlotte Zwerin’s masterful juxtaposition of images. These are the images of everyday life in America, then and now . . . solitude, the road, alienation, a distant memory of home, real or imagined that brings us some comfort, set to the tune of a muzak version of the Beatles’ “Yesterday” played on a warped record. We navigate through its absurd nightmares and the childlike innocence, searching for whatever it was our forefathers were promised either 200 or 20 years ago, and are now perhaps attempting to purchase instead.