Reviews

Is the beginning even the beginning? It’s a question I posed in my head about halfway through Jim Jarmusch’s The Limits of Control, first literally and later philosophically.

Spirited, exciting, and richly entertaining though it may be, the latest Star Trek doesn't even try to be a good Star Trek movie—and by the standards of the franchise, it certainly isn't (this seems to be Abrams's apparently successful trick).

Christian Petzold’s Jerichow plays like a modern riff on The Postman Always Rings Twice, with a globalized European spin.

Olivier Assayas has said that his intention with Summer Hours was to return home and make a “French film” in the wake of his globetrotting trilogy of demonlover, Clean, and Boarding Gate.

A quintessential work of muckraking journalism outfitted as a mainstream talking-head documentary, Outrage doesn’t lack for nerve.

If Atom Egoyan weren’t in such a hurry to cram all sorts of up-to-the-minute gewgaws (vidchats, xenophobia, handheld video recorders, even terror attacks) into the unwieldy, disjointed contraption that is his twelfth feature, he might have turned out a mildly entertaining piss-take on 1940s B-grade family melodrama.

Flower treats the preciousness of its two young protagonists as a given, and accepts with grace and dignity the fact that they (along with all the rest of us) will have to learn how to navigate an imperfect world.

According to IMDb, the working title for Obsessed was Oh No She Didn't, a factoid that, though too good to be true, I’m inclined to believe.

Aghion turns her DV camera on a quartet of geologists searching for fossils of plant life that would suggest a formerly tropical Antarctica, but the goal is less important here than the painstaking portrait of their needle-in-a-haystack search.

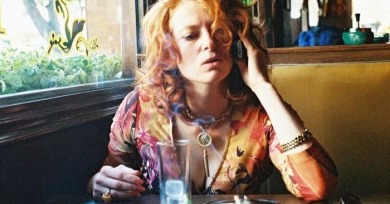

Julia is your typical tale of redemption, even as it thrashes against the sentimentality such a designation implies.