Reviews

Turkish director Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s slow, stunning Once Upon a Time in Anatolia begins with a long nocturnal search for “the place.”

The film is superbly written, but it's also smartly directed, insofar as there’s a continuity between its writer-director’s ideas and the visual language he uses to express them.

Most people who pay top-dollar to see Brad Bird’s Mission: Impossible—Ghost Protocol in IMAX will likely never notice that, as the film sprints along, the size of the image changes with some regularity.

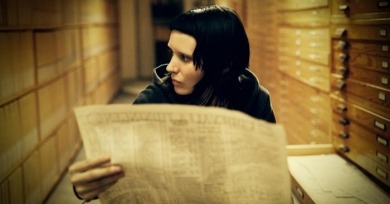

David Fincher has made a career of turning pulp into prestige.

There’s really only one thing you need to know about Albert Nobbs: that it was a long-gestating dream project for Glenn Close.

A claustrophobic bourgeois horror story about two couples of Brooklyn parents who meet over cobbler and coffee after one of their sons strikes the other with a stick, Reza’s play has superficial similarities to previous Polanski films like Rosemary’s Baby, Cul-de-Sac, and Repulsion.

In this follow-up to Marshall’s similar ensemble romcom from 2010, Valentine’s Day, a bedridden Robert De Niro’s dying wish, croaked out of the side of his mouth in the manner of his Flawless stroke victim, is to be allowed onto the roof of his New York City hospital so he can see that precious ball drop one last time.

The Lovely Bones had camp escape hatches in Stanley Tucci’s wormy-squirmy serial killer and Susan Sarandon’s boozy grandma. We Need to Talk About Kevin offers no such exit from its suffocating vortex of self-serious exploitation.

here is a seam of self-deprecation running through British spy films that stretches back to Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes—that of the comparative dullness and vulnerability of Britain when confronted with a fearsome and organized European menace.

It’s a film that is a proclamation as much as it is a movie, a cause as much as an entertainment: this is cinema, it says, don’t let it die.

Sleeping Beauty is withholding to a fault, providing only the barest scraps of information about protagonist Lucy (Emily Browning), a perverse set-up since affording her a voice and the expressive capacities of consciousness would seem to be the film’s raison d'être.

Steve McQueen’s Shame is the latest entry in what we’ll call the sad sex subgenre. In a sad sex film, partners don’t enjoy each other’s flesh, they rut. They bump uglies. They shudder. Their faces evince no enjoyment as their bodies try to make contact. Sometimes they cry during orgasm.

As if A Brighter Summer Day’s four-hour length weren’t intimidating enough to the uninitiated viewer, Yang makes sure to weigh his film down from the get-go, both formally and thematically.

The recreation of the structure, pacing, and visual delights and imperfections of silent films is nigh on flawless: certain movements of characters appear artificially quicker; the intertitles frequently don’t match the words being said on screen, and are drafted as they would have been then.