Reviews

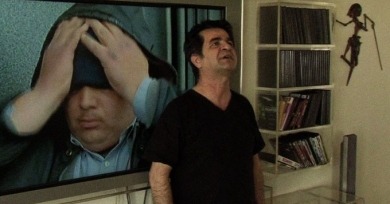

This Is Not a Film—which Panahi made while under house arrest awaiting sentencing, collaborating with his friend, the documentarian Motjaba Mirtahmasb—is more than a great, devastating piece of moviemaking; the movie is something of a cinematic miracle.

If you’ve ever pondered the daily existence of a pedophilic predator who keeps his beatific ten-year-old sexual object locked in a special basement room—what he looks like, what he eats, what television he watches—Markus Schleinzer’s Michael might just be the film for you.

Films about the experiences of returning veterans have long been on American screens, from 1946 Oscar-winner The Best Years of Our Lives to 2010’s The Messenger (one of several recent contributions to the genre), but writer-director Liza Johnson manages a fresh, surprising approach to the subject matter.

Moverman seems less interested in the particulars of the misconduct than in conducting an experiment in perspective.

Even if the film does rely somewhat too heavily on Radcliffe opening doors and lighting candles at the expense of deepening its world for a more free-floating dread, it must be acknowledged that it’s often scary as all get out.

This is consumption not for pleasure or taste, but to achieve the most meager of sustenance. The Turin Horse repeats this routine with each new day, each time with the cadence and solemnity of a religious rite.

One of the problems with found footage movies like this one has always been, and continues to be, the need to regularly re-establish the vantage point from which the images we’re watching are being captured.

Some horror movies send you off into the dark night giddy with fear and pleasantly reeling from revulsion. Others give you a glimpse of something so dark and bleak that you’re left with a queasiness in the pit of your stomach.

Liam Neeson has a very particular set of skills, skills he has acquired over a very long career. These include being an authentic hulk: before he worked with Steven Spielberg and Atom Egoyan, he did background-brute duty in Krull and The Delta Force.

The hysterical acrobatics of 1Q84 reek of an author trying to recapture magic, but, having read too many of his own reviews, failing. For those seeking to recapture the Murakami that wowed in the 1990s, Tran’s sensitive, singular adaptation of his small, lovely book isn’t a bad place to go.

Ralph Fiennes’s Coriolanus is the work of an actor obsessed. Fiennes first tackled the part of Shakespeare’s opaque Roman general on stage in 2000—then nursed a decade-long fixation to bring the infrequently staged play to the screen.

Up until now, Mexican director Gerardo Naranjo’s movies have seemed more devoted to energy than content.

Though Robinson never once appears onscreen, he is nevertheless a compelling and well drawn character. Seeing the world through the images that he created induces a feeling of greater intimacy with him than the traditional cinematic set up of relating face to face ever could have.

Rosi’s clearly spent some time pondering documentary strategies and avoids conventional solutions to let his film breathe.