Children of the Evolution

Jeff Reichert on The Tree of Life

“There is grandeur in this view of life . . . from so simple a beginning, endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.” —Charles Darwin

When Auguste and Louis Lumière first shined a light through a thin celluloid strip imprinted with sequential images, casting the shaky, colorless, but nevertheless strikingly realistic representation of an arriving locomotive onto a screen set before an audience, they could never have imagined their simple beginning—a hand-cranked gadget that elegantly paired cutting-edge photochemical processes with basic mechanical know-how—would beget something as wondrous as Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life. Yet, it did. The world-changing evolution from that Point A, one shot of only fifty seconds in length (though apparently L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat was not programmed as part of their inaugural demonstrations—the tale of cinema, as always, exists at the meeting place of science and myth), to Malick’s Point B, weighing in at around 8,280 seconds with hundreds of discrete shots, has been considerable. We take it for granted somewhat that, especially since the advent of sound, how cinema works has been consistent, immutable. However, the countless New Waves, dead ends, discarded technologies, and breakthroughs we’ve seen since 1895 attest to a pliable medium always in flux, even if the meaningful changes may not be apparent at the moment they occur.

Though separated by over a century of cinema, L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat and The Tree of Life share a fundamental sense of wonder: at the image, at the world, at the fact that we are able to capture pieces of its beauty in images. The more things change, the more some things stay the same. The Lumières couldn’t know their single-shot story would grow into Malick’s radical, flowering montage, but neither would a Precambrian single-celled microorganism have predicted it would grow to be a dinosaur, a fish, a tree, or Terrence Malick. The beauty of evolution lies in its mystery—we can only witness how it unfolds in retrospect, making our position within Darwin’s Tree of Life no more privileged than any other.

Appropriately, Malick’s work—not only named after the fourth chapter of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and its famous tree-shaped sketch representing the fundamental law of nature the English naturalist would be the first to describe but also infused with and devoted to its spirit—takes place in hindsight. Jack O’Brien (Sean Penn), as uneasy in his skin as Malick seems to be behind the lens when shooting the glass offices in which Jack works as an architect in modern day Houston (Malick’s always looked to the past for his stories and seems both nervous and awed at the sights of the contemporary world), recollects on the tree of his own personal evolution. His sun-dappled memories of growing up the eldest of three in Waco, Texas (like Malick), may form the bulk of a work that comfortably spans time, but The Tree of Life isn’t mere memory play. Jack’s childhood is framed as one small part of a truly universal story. (Tellingly, the film doesn’t even open on our hero, instead starting with another beginning: a childhood recollection of his mother’s.) It isn’t long after we’ve met him that Malick flashes back to the beginning of his story: not birth, or conception, or his parents’ first meeting, but the Big Bang.

The Tree of LIfe is perhaps most striking in its sui generis hairpin turns from the macro to the microcosmic; Malick destroys time in the space of the cut, yet for all its leaps, his film feels completely the result of grand design. Cinema has been held in thrall to the long, intricate take, absorbing without question the Bazinian notion of the camera as somehow capturer of truth, virtuosic choreography of the lens through space the sign of artistry and engagement with the material of the medium. This bias quietly underlies some of the early criticism of Tree’s unceasing stream of imagery. Malick’s taken the opposite route to a purer kind of filmmaking—his cinema’s first priority isn’t to communicate space (most often the realm of story, the shackle of earlier arts that has limited cinema in its first century), but rather to capture feelings and evoke moods. He does this by vigorously slamming shot against shot against shot, continuity be damned, and often flaunted. He’s cinema’s very own Large Hadron Collider and the discoveries captured in The Tree of Life might well point towards an evolutionary advance for the medium.

Even with cosmic ambitions, Malick doesn’t discard story; he just tells it using tools indigenous to cinema. His recognition of the essential links between human corporeality and cosmic infinitude (we are made of the same stuff as the rest of the universe after all) can best be captured through editing to make connections that transcend space and time. Through careful cuts and shot-making, the flow of memory, too, can be evoked better than in any other form; the moments that comprise Malick’s radical montage of the O’Brien family’s evolution never flirt with cliché, yet remain powerfully evocative and approachable. Young Jack accuses his father: “You’d like to kill me.” He later convinces his blonde, beatific brother to hold his index finger up to be shot by a BB gun. Ripped from context, these moments speak of the inchoate rage children feel for their parents and siblings; but when placed in Malick’s epic chain, they open up, revealing the burning jealousy and resentment of the unfavored son, and also life’s need to compete and survive. For a film whose setting is, broadly, the known universe (or, perhaps, “Creation”), its concerns are often terribly familiar and easily tangible. Has there ever been a film with such cosmic grandeur that still remains so human?

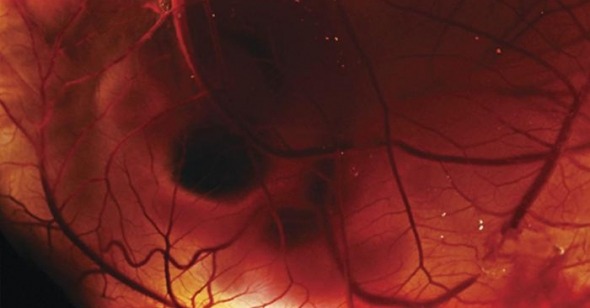

The Tree of Life’s most radical detour (the film is itself, a radical, unthinkable collection of detours) is a drop-in on the Mesozoic era after a sequence of shots tracks the birth of life on Earth. A raptor-like creature emerges from the forest and wades into a stream. At the opposite bank lies a wounded herbivore. The predator scampers over cautiously and apprehends his prey’s immobility. And just as we expect carnage (thanks to conditioning from Jurassic Park and its sequels), Malick provides instead, grace. The raptor, who has pinned the injured creature with one clawed food, shares a moment of silent communion with the wounded dinosaur, releases his grip and then leaves. This may seem an unlikely moment in the animal kingdom, even less so in the kingdom we can only know through the fossil record. But does Malick exhibit hubris here by applying a naive anthropomorphism to the scene, or do those who criticize do so by suggesting he’s necessarily incorrect in his vision, tacitly implying grace to be the sole provenance of humanity? A frighteningly elegant shot of a comet devastating the planet, and the dinosaurs with it, reminds that we’ll likely never know for sure.

Most who see The Tree of Life will be unaware of Darwin’s Tree of Life and the quote at the top of this article. The film’s fundamental, yet often porous distinction between nature and grace, though bequeathed to us by Aquinas, is heavily filtered through Darwin, himself a Christian for much of his life and a student of theology before he began his exploration of the natural world. His theory of the origin of species may be derived from the rules of nature, but he finds room for grace in it as well. Malick, too, is a scientist as well as a theologian-philosopher (on a very concrete level, we can marvel at the wondrous practical effects created with Douglas Trumbull using liquids, dyes, and modified cameras, instead of digital technology). The film’s headiest mix of science and theology comes at its conclusion. This is no mere cookie-cutter view of an afterlife: as all of the characters we’ve met on Jack’s journey through memory (and some we haven’t, suggesting the film world captured, but left unseen) converge on a beach, it may look like a Mike & The Mechanics music video, but I believe I spied in it an attempt to make the boundaries between past, present, future, self, and other meaningless. It’s a conclusion that several strands of contemporary physics points towards as well.

This is our fifth article in a single week about The Tree of Life. My colleagues’ wonderful earlier entries delved into metaphysics, trees, childhood, and dinosaurs, among a host other topics. I feel confident in predicting you haven’t seen the last of Tree in these pages, and I’m excited to see what other readings it lends itself to. When we recounted our favorite films of 2010, Andrew Tracy wrote of our pick for the best film of the year, Pedro González-Rubio’s Alamar: “In a cinema world where hard-and-fast distinctions (New Waves, schools, and the like) condition both creation and reception, Alamar testifies to the endless pliability, the innate and uncontrived complexity of the medium itself—its indefatigable constancy even as its very matter changes.” Sounds not unlike life. Perhaps ten years from now, every film will look and feel a little more like The Tree of Life. Maybe none will. There’s enough grandeur in it that it can stand alone. While watching the film, remember that its unutterably complex, meaning-laden cavalcade of images evolved from a single shot of a train pulling into a station captured over a century earlier. There’s grandeur there as well.