Alas! Poor Europe

by Leo Goldsmith

Film socialisme

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard, France/Switzerland, Wild Bunch

Film socialisme is the 27th Godard film to play at the New York Film Festival, and with nouvelle vague luminaries like Rohmer, and, most recently, Chabrol dropping like flies, more than one recent reviewer has speculated that this may be his last. It’s a morbid thought, wholly unfounded by any particular knowledge about the director’s health, but perhaps it’s at least partly informed by the rather mordant tone he takes with his new film. Though Godard’s latest nudge at the limits of cinema parades a number of the director’s usual puckish gestures, multilingual plays on words, and provocative image-puns, it’s nonetheless a dour archaeology of the roots of our cultural end times.

Godard has always been interested in the interplay of signs and symbols, but this tendency seems to have reached a fever pitch in Film socialisme, which is rather less utopian than its title suggests, but is instead a kind of mise-en-abîme of video anarchy. An onslaught of ancient hieroglyphs and pop cultural icons flood the frame, and Godard employs often agile palimpsestic editing tricks to filter them through the dense, accreted grain of DV and recode them into a half-dozen (spoken and written) languages. (Some of these are head-slappingly obvious, like his overlaying of Hebrew text over Arabic.) And to be still more difficult for the English-speaking market, Godard has provided his own barely helpful subtitles in fractured monosyllables (“nocrimes noblood,” etc.) that the director describes as “Navajo.” (He means they’re for imperialist American consumption.) Buried somewhere in this chaos there’s definitely a point—quite a few, in fact. But as has become the norm for Godard, it’s less an essay film than an annotated bibliography in video form, sourcing clips from John Ford and Agnès Varda, quotations from André Gide and Curzio Malaparte, and a wealth of archival footage of world warfare, soccer highlights, and cheesy TV travel and history shows.

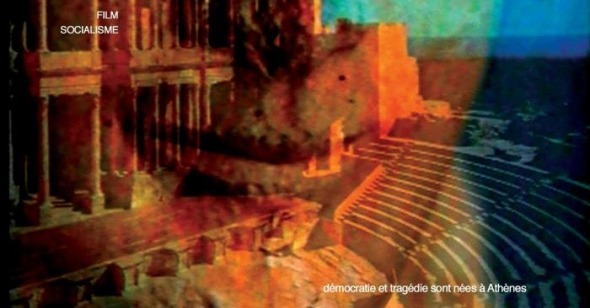

Out of this frenetic détournement, Godard constructs a lopsided three-level architecture: a first section that follows pan-European tourists on a luxury cruise around the Mediterranean; a lengthy second part concerning the enmeshed familial and political strife centered around a rural gas station; and a coda that editorializes in pure video collage. And somewhere amid this barrage is Godard’s very own éloge d’Europe, its checkered patrimony, and deeply uncertain future. In grand polemical portmanteaux and wordy witticisms, the director obliquely decries the compound betrayals of Greece, Palestine, Africa, the Jews, and perhaps even the very idea of a viable socialism. Here as elsewhere in Godard, history is awash in a sea of big, dirty words—MONEY, OIL, GOLD—from which none of Europe’s cultured elite escape unsullied. The first section’s amnesiac pleasure-cruisers are perhaps the most drenched because they are the most in denial: adrift in a de-territorialized Mediterranean of the mind, they enjoy aerobics, casinos, discotheques, art marts, fine dining, bars that double as churches, and others that are simply decorated to look like churches, and they are able to ignore, for example, an offhand song by Patti Smith who wanders the elevator banks with her guitar, or a lecture by philosopher Alain Badiou on Husserl’s theory of mathematics.

In other words, for Godard, these are the worst kinds of scum, and the most entertaining parts of Film socialisme find the director sneering at the denizens of this ridiculous Baudrillardian EU-simulacrum, which only seems to exist to make the real Europe appear more solid. Godard spends much of the first part of his film energetically deconstructing this fantasy with an arsenal of audiovisual weapons—amazingly cruddy camera-phone images and brash, deafening wind noise in his microphone—while staging studied vignettes featuring a cosmopolitan cast (Germans, Arabs, and French) that nearly evoke some of the blithe satirical spirit of his early work. Figures gaze off into the Mediterranean waves, intoning about the continent’s many holocausts and disgraces (like the mythic conspiracy of the circulation of Spanish gold to Moscow, Germany, and France via the International Communist Party), while Godard impishly manipulates the form with loud bursts of forbidding strings, brutal maxed-out sound textures, and nasty phosphorescent exposures. Mostly, Godard disallows any of these characters from being anything but totemic—including Patti Smith and the underage girl whose cleavage the camera ogles—but some manage to resonate beyond, perhaps, any particular agenda. For example, one aside about a Jew”-ish” businessman named Goldberg (or “gold mountain”) stands out for some critics as a possible anti-Semitic dig against Hollywood Jews. (This interpretation seems off the mark, but nevertheless Godard has already refused the honor of receiving his very own “Jewish gold” statue at next year’s Academy Awards ceremony.)

In the film’s second movement, which takes place at a gas station operated by the Martin family in rural France, the tempo and mood lighten somewhat, but not so much for the better. Godard continues to deny the film anything like a narrative, opting instead to stage cute but rather empty scenes (a girl with a llama reading Balzac, a boy with a “CCCP” t-shirt pretending to conduct an orchestra) and to ventriloquize at length through the nonprofessional actors. (I will admit that my so-so French and patience for the “Navajo” were wearing thin here, but this section of the film came off to me like yet another questionable attempt by the director to say something about French youth.)

What this sequence does allow Godard to do—first through a brief quip about a Renoir painting and then again in the film’s epilogue—is to address the question of artistic property, which speaks perhaps more clearly to the film’s slippery title (and intent) than any other. As the director has stated in interviews, “The socialism of the film is the undermining of the idea of property, beginning with that of artworks,” and to drive home this point about forcible artistic property redistribution, he concludes the film with a shot of the infamous FBI warning and a quotation from Pascal: “If the law is unjust, justice proceeds past the law.” While Film socialisme is less likely to collectivize audiences than to divide them—by class, gender, and politics, as well as by country and language of origin—Godard’s point is nonetheless timely and boldly asserted. Amid this roiling ocean of images, text, and ideas, most of which seem to disappear into their own navels, this bold jab at notions of intellectual property actually strikes a resounding and highly relevant chord.

And in practice Godard himself seems for once to be wholly clear on this point, having recently donated €1,000 for the defense of an accused French MP3 downloader. Of course, the Film Society of Lincoln Center and distributor Wild Bunch are not so radical: they recently tried to shut down a sub-rosa premiere of the film in Brooklyn by the radical collective Red Channels. It’s unclear if the pre-premiere actually happened or not, and who knows if Godard would have approved? After all, at that screening they were going to use real subtitles.