Reviews

The Village seems acutely aware of the relationship between filmmaking and mythmaking, an inquiry all too welcome in the face of society’s current desire to dead-end culture into the morass of reality television.

In contemporary Hollywood product, shopworn words like “honor” and “loyalty” turn up as frequently as “freedom” and “liberty” in a George W. Bush campaign speech, and with similar impact.

With its three hours nearly all comprised of clips from other people’s work and selections from the public record, Los Angeles Plays Itself, while impressively comprehensive, never pretends to be empirical in its approach.

“The American Problem,” so-called, has undeniably been the Cannes-defining cog around which the hot-button cinema of the past two-plus years has rotated.

Just as musical taste is as individualized and unaccountable as a predilection for shellfish or eggs-over-easy, Spike Lee’s films are as personalized as those of any American director working today.

Though its narrative precision has a way of making decisions feel predetermined, Maria Full of Grace benefits from these jarring transitions, its point-to-point speed deepening our sense of Maria’s impulsive character.

Though lacking the fantastic flourish of, say, a King Ghidorah or a Megalon, there’s something perfect, almost classical, in the form of Godzilla.

The real and filmic horrors channeled into our living rooms 24 hours a day, the instantly accessible physical reality (actual or simulated) of mass death has paradoxically pushed the apocalyptic further away.

There’s something disconcerting about the fact that you’d never guess Father and Son was made by the same filmmaker responsible for its precursor, Mother and Son.

For all the chatter about Quentin Tarantino’s cultural sampling and border jumping between high and low art, his (white) elephantine opus acts more like a colonizer, staking out a self-contained retro-vacuum where our hunger for art in American movies can thrive on faith divorced from accomplishment.

Pitt’s personality vacuum as Achilles means that we don’t particularly care if this super soldier goes along. Meanwhile, as Troy is governed by the doddering old fool King Priam (played by that expert doddering old fool, Peter O’Toole) and its young prince Paris is, basically, a self-absorbed knob, there’s not much reason to care about its citizens’ fates.

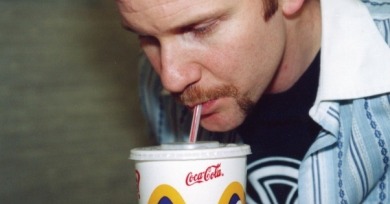

I wish that I could say “mission accomplished,” but my mouth is currently full of fried fish goodness. Consider it a perverse act of junk food solidarity from me to you, Mr. Spurlock. May it bring you fond memories of Day Eight.