Love, Actually

by Matthew Plouffe

Son frère

Dir. Patrice Chereau, France, Strand Releasing

I’ve never been in the same room with Patrice Chereau, and yet the mere mention of his name elicits the kind of fondness I might feel for an old friend, one with whom I’d delight in exchanging the year’s stories over a bottle of wine on infrequent drop-ins—due to the wealth of catch-up topics, conversation rarely goes flat, and the occasion justifies all cost and consumption of the wine. No doubt this sense of intimacy (incidentally the title of his last film) with the filmmaker is due to in part to his proclivity for stark, subtly infused humanism—a potent dose of Chereau tends to purge affectations we develop as inveterate filmgoers (for better or for worse), settling the stomach at 24 effervescent fps. On bittersweet departing one’s left with a misty memory that words of import were spoken, that for two hours, human interaction rose above facile office pleasantries and put-ons to a richer, more honest plane of communication. Thankfully, he never loses our address. Thankfully, he’s back.

Son frère chronicles the slow deterioration of a diseased thirtysomething, the concurrent rebirth of a brother’s bond, and may be among the filmmaker’s most affecting works to date. Distinctly Chereau in its tireless efforts to eschew the phony hyper-real hospital milieu so commonly splayed out on the big screen and utilizing a kind of medium-as-message visual grit, the luminous naturalism of Those Who Love Me Can Take the Train (1997) here founders into a stewing pot of elegantly rancid realism—suffice it to say that in-patient living in the city of lights has never looked worse (in great part due to DP Eric Gautier’s masterful photography). Miasmic hallways, sputtering coffee machines, and jaundiced light haunt the Paris hospital in which much of the film unfolds, trumping all gruesome effects of disease. Yet the most disturbing regions probed by Chereau are not concerned simply with health care verisimilitudes. Son frère plunges to the depths of familial resentment, disinterring a love so often buried beneath years of deleterious grudge and repression, a love which fuels this quiet examination of ardent loyalty, unconditional understanding, and simple sacrifice.

An evening phone call catches Eric Caravaca’s Luc off guard. “What are you calling me for?,” he asks, moments before his estranged brother Thomas (Bruno Todeschini) irrupts into the apartment muttering about some platelet-destroying sickness he’s been hiding, a relapse, enervation, interjecting commentary on the flat, fussing, crying, and admitting that he’s “scared shitless.” It’s the last time we see Thomas in command of his body and yet an unmistakable dust of awareness is kicked up in this desperate din; deterioration looms large over the sick man, a reminder that it won’t be long now. “Something in my system’s gone haywire,” he says, but it’s not AIDS, not cancer; all he offers is that “something a little more exotic” is at work. In his consternation, making the most of a dwindling lucidity, he asks only that his brother accompany him to the hospital the following day.

As the film ricochets between two disparate times and locations—that dreary hospital in late winter and Luc’s Brittany chateau in the summer—character arcs delicately unravel and shards of potent back-story are revealed. In typical Chereau fashion, no one, the protagonist of L’homme blessé included, is conceived free of fault or flaw, but the filmmaker opts to leave us with Luc, a reticent audience to this dance with death. Lingering at the corner of the room, keeping a calculated distance from disease, he plays mediator on cursory and denial-driven visits from Mom and Dad (Antoinette Moya and Fred Ulysse), offering the neglected girlfriend Claire (Nathalie Boutefou) an understanding ear. For those who have witnessed one person’s sickness drag an already friable family into a dire state of decay, Chereau’s querulous manifestations of pain and the hazy and fetid contrails left in their wake are sure to elicit gut-wrenching reactions.

“Why wasn’t it Luc who caught it?” a father finally roars in front of his sons, professing platitudes about attitude and its ailment-alleviating virtues. Claire too, succumbs to some base need for connection and turns a warm embrace with Luc into a moment of face-flushing kisses. It’s the kind of charged cry that dapples the film; tiny explosions of rage and sexuality wriggle from the muzzle of guilt keeping residual suffering at bay, surfacing unexpectedly, splintering muted masks of acceptance. The fragility that disease relentlessly fingers, a snicker of death turns the family into mere marionettes—this is the reality of grief, the most complex and confused of emotions, handled with a gripping and subtle grace by the unerring hand of an artisan.

It’s those works that properly deal with disease that also seem to play out like the finest of war films: with hospital as battlefield, sickness kills, maimes, unites, and polarizes, so often a numbers game with so few left standing on either side. Drowning in the sounds of dementia that echo this similarly reason-free dialectic of disease, Luc wanders the hallways passing pallid patients dragging drip IVs, once meeting a frightened young man with a scar running length of his stomach. When Manuel (Robinson Stévenin) lifts his robe to show Luc that he has been cut open “a bit like a fish,” the healthy thirty-year-old quiets, guilty, before reaching out for the boy’s arm in some silent missive of understanding from one casualty to another.

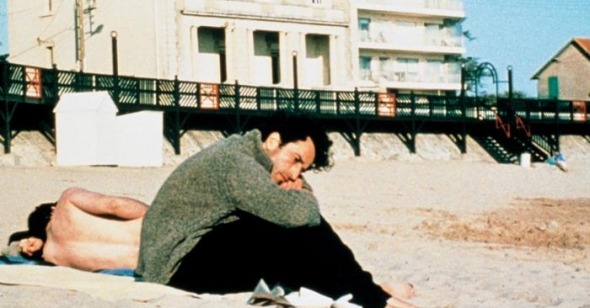

Even the beachside becomes an all too pristine prison camp in which the brothers duke it out. As Thomas’s pained gait and brittle limbs signal a physical deterioration, put-on sibling chitchat quickly turns to rebarbative bickering. “You’ve always preferred guys?,” he asks point blank, inquiring about Luc’s homosexuality, a point of touchy misunderstanding which pushes Luc towards the ineluctable edge of martyrdom. “I don’t owe you anything, nor am I giving you anything,” he explodes, renouncing his position as caretaker, “I’d do this for anyone…I don’t care if you deserted me. I’m here aren’t I?” And in truth, martyr or not, nothing more needs to be said. Though he confesses to feelings of defeat to a caring boyfriend (Sylvain Jacques), Luc’s ultimate act of faith in the face of all these horrors is simple: he remains.

As Thomas’s limp body is prepared for surgery on the eve of a last ditch splenectomy, Gautier’s lens quietly considers what may be the film’s most powerful scene: two nurses who strip the patient naked and slowly shave off all of his body hair. Stretched out across the bed, barely conscious as they take care to hide his genitals while performing this dark ritual, the image of Thomas, slave to sickness, unwarmed by the trite verbal coddling of Death’s calloused handmaidens, lingers long after its end. In quick cuts Chereau reminds us of Luc’s presence, of his courageous gaze all the while. If it’s his triumph that Luc faces the daily tragedy of such immeasurable violation without ever lowering his eyes, it’s Chereau’s that he makes one wonder how anyone could make it out alive.

“I really love you,” Thomas says on one of his final days on the coast. “I wanted you to know it.” “Yeah, I love you, too,” his brother responds. A final act of understanding, of utter comprehension and compassion to be exact, illuminates this shimmering monument to brothers. The simple denouement that closes the chapter on Thomas’s illness, finally allows him the moment of dignity he has been denied all this time. Chereau reminds us it is a brother who so often knows best, who can consider the world through the heart and head of that person to whom he is intrinsically linked. And as Luc cleans up the lawn chairs, contemplating his final act of faith in and for his only brother, the old man they’ve befriended walks by the end of the driveway and offers one small statement tinged with hope, “It’ll be nicer tomorrow. Even if the weather was fine today.”