Star-Spangled to Death

Michael Joshua Rowin on Dogville

I’m sick and tired of hearing about “America.” Not the country, but the word, as it stands now as a meaningless adjective. Like the dollar, it isn’t worth much anymore. Notice how what gets depreciated is thrown around like so much cheap dirt—not only in tastemakers’ and politicians’ unoriginal, cynical appeals to “American values” and “American democracy” (in the face, of course, of “un-American” dissent), but also in the lazy titling of recent movies purporting to parody traditionalism or, to bring up another outmoded phrase, “the American Dream”: American Beauty, American Psycho, American Movie, Team America: World Police. The attempt to critique our society and its phony patriotism becomes compromised in the mere use of this obsolete word. Because to take this insidious word for granted in its usage—even in irony—is to reinforce assumptions of what “America stands for,” a facetious appeal to ideological collectivity.

If I seem to be overemphasizing semantics in what should be a paean to one of the year’s best films, it’s because I’m through with worn-out epithets and manipulative euphemisms. Which, yes, brings me to Dogville. Say what you will about Lars von Trier—I won’t deny that he can be an obnoxious self-promoter, and at times, as in the case of a wreck like Dancer in the Dark, a bad director—but he absolutely does not unthinkingly mimic the hand-me-downs of artistic expression. Does this automatically ascend von Trier to the realm of political filmmaking? I still don’t think so—there’s too much shock-the-bourgeoisie silliness remaining in his creative instincts—but it does make him capable of producing some brilliant social commentary.

Let’s start with the title: Dogville. A village of dogs. That’s what von Trier curtly deems this great nation of hucksters and hypocrites and religious fanatics. Sure, it ain’t subtle, but when expressing rage no one should be. So with the aptly named Dogville von Trier initiates a new trilogy which deals with the American question—but this isn’t the same American question posed for easy irony’s sake by the aforementioned artistic statements. By confronting the Good Samaritan community-based myth upon which the United States is built and prides itself on, Dogville exposes America’s current global role as a hollow sham in light of its projected image as the democratic ideal. That so many people got it wrong and took von Trier’s allegory as an affront to the American citizenry only affirms how deeply and stubbornly this myth is embedded in the national consciousness.

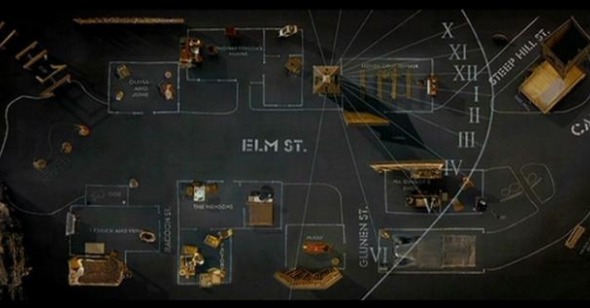

In a year of so much ridiculous, bombastic nonsense (and I’m only referring to political campaigns), I love how von Trier found the perfect visual corollary to his streamlined, though epic, allegory. While it’s not quite a local experimental theater exercise (can von Trier ever fully abdicate his showmanship?), Dogville’s construction on a soundstage, with chalk-lines and meager décor forming its parameters, certainly lent it the most enduring mise-en-scène, or anti-mise-en- scène—one that was etched in my mind all year round. Just watching von Trier’s actors navigate this space, make it their own, and then, for a grand finale, burn it all to the ground was thrilling. Being part of a New York Film Festival crowd that reacted so viscerally to von Trier’s turning of the tables on his well-documented misogynist leanings and Dogville’s own moral universe was even more so.

Even the most enthusiastic cinephile falls into ruts when it seems as if filmgoing is merely an endless series of hermetically sealed, comfortable viewing experiences. I’ll never forget how at its aforementioned NYFF screening a certain gentleman stood up and cursed Dogville as “hateful shit” during the film’s now infamous end credits montage of impoverished, destitute Americans down through the ages, scored to Bowie’s “Young Americans.” It doesn’t impress me that Mel Gibson jerked tears from a Christian populace with a bloody Passion play; it does impress me that, after all the empty, complacent discourse on “America,” a director got underneath the skin by contesting the validity of America the Myth. Granted, that end credits sequence is not von Trier’s finest moment, and given some of his previous gimmicks, that’s saying a lot. But I’m willing to forgive it due to the three hours of cinematic bliss preceding.

I don’t want von Trier to practice restraint. There are too many safe artists with access to way too much money to wish for such a thing. Similarly, there’s way too much partisan bullshit on both ends of the political spectrum to wish for filmmakers who, like Michael Moore and Mr. Gibson, rile up their loyal bases, doing away altogether with dialogue and rumination. Dogville makes it clear, or transparent, that any such base is a threadbare collection of fear and paranoia; the film refuses to pander to any constituency, or any straightforward political persuasion. Von Trier’s didacticism isn’t simple, but a challenge to anybody without a pulse on 21st-Century groupthink, a gut-punch statement on the erosion of liberty, community ethics, and instruction with society’s pursuit of well-intentioned exploitation. I’m not unaware of the difficulties of, and contradictions within, his instigations. But because of his iconoclastic intelligence and uncompromising experimentation, when von Trier speaks about America through his films—as he thankfully will in the next few years—I’ll listen.