Class Clown

Elbert Ventura on Crimson Gold

Iranian director Jafar Panahi’s newest feature is called Crimson Gold, but it could just as easily share the name of his previous movie, The Circle. Both banned in their home country, they harbor the same vision of a circumscribed society. In The Circle, a daisy-chain of humiliations emblematizes the subjection of Iranian women, eventually ending in prison, where Panahi, milking his metaphor to the last drop, closes his doleful chronicle with a 360-degree pan of a squalid cell.

Crimson Gold’s circle is less literal, but it suggests a fate no less ineluctable. The opening shot, a stunning long take from a fixed camera, dispassionately observes the fumbling stick-up of a jewelry store. Alone in the shop, the gunman threatens the recalcitrant owner but the heist ends badly: alarms go off, bystanders gather outside and automatic bars seal the robber in. His doom imminent, he shoots the jeweler and yells at the people outside to stop staring. Then, he puts the gun to his temple and pulls the trigger. Thus the movie begins—and ends.

Opening with its climactic act of desperation, Crimson Gold has the momentum and pall of inevitability. The botched caper bookends an episodic story that serves as a tour of urban Iran, seen through the eyes of a forgotten soul—a humble pizza delivery man who comes to realize he has little to live for and, hence, to lose. The fatalistic air, not to mention the use of a crime as the portal to a broader critique, is redolent of film noir. But the movie resists the genre’s narrative contortions. Thoroughly lacking in duplicity, it’s a resolutely naturalistic picture, privileging the banal and uneventful with its uninflected gaze. Much like the movies of Abbas Kiarostami, who wrote the script inspired by an actual event, Crimson Gold is preoccupied with the stuff of daily life, more neorealist than noir. It’s that devotion to the small, accumulating failures of an unexamined life that gives its defining jolt of violence a poignant sting.

The movie’s animating presence is a dead man walking. Hussein (Hussein Emadeddin) navigates the streets of Tehran with a perennial scowl, the meek sputter of his moped his frequent accompaniment. The delivery gig is a potent metaphor for this underground man: always on the move, Hussein is reduced to passively observing the life teeming around him. He’s literally on the outside looking in: peeking in though ajar doors, he steals momentary glimpses of new, unattainable worlds. Martin Scorsese employed a similar device in Taxi Driver. Stuck in his cab, Travis Bickle floated through the streets like a wandering specter, watching helplessly as possibilities materialized and vanished on a nightly basis. For both men, there is neither entry into that realm nor exit from their own.

The sad-eyed Emadeddin, like many of recent Iranian cinema’s performers, is a non-professional actor, yet his Hussein ranks as one of the most indelible protagonists in contemporary cinema. A bit of a cipher at the outset, piecemeal clues to his persona suggest a well-liked man cursed by an unspecified health problem that requires him to take cortisone (alluded to as the reason for his stocky frame) and an awkward taciturnity. The air of defeat clings to this hangdog bear from the get-go. Hussein’s fatal arc is launched when his friend, a chatterbox named Ali (Kamyar Sheissi), brings him a found purse. The contents are meager, but something catches their eye: a receipt for an expensive necklace. Set to marry Ali’s sister, Hussein goes with Ali to the upscale jeweler, only to be turned away. A return trip with his fiancée only causes more humiliation, as the trio, after some tense browsing, are gently told to try the bazaar instead.

The nights aren’t much better. On the job, Hussein encounters a fascinating cross-section of modern Iran. One delivery leads to a clumsy encounter with an old army buddy who greets him warmly and shoos him away with a hefty tip. Another call takes him to an apartment building staked out by police, waiting to pounce on revelers at a party upstairs. Refused entry by the cops and yet prohibited from leaving the scene, Hussein joins their vigil and distributes the pizza—an unlikely form of communion for the group. Taking a spot next to a wide-eyed, 15-year-old soldier, the two can only stare up in rapt wonder at the chador-less silhouettes in the window.

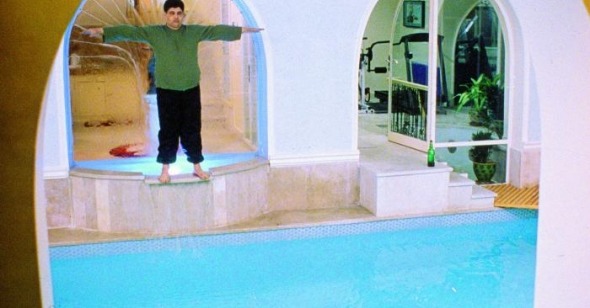

It’s a midnight delivery to a rich part of town that turns out to be his last. Greeted at the door by a harried young man, Hussein is invited in to keep his customer company. The condo is a palace, complete with an indoor pool and a killer view of the city. The man feeds Hussein pizza and wine and talks into the night. All hopes of a connection are illusory, however. A phone call interrupts their session. Left to his own devices, the inebriated Hussein lolls around the splashy digs, each new trapping—an exquisite rug, a stately piano—an imperceptible blow to his dignity. Following a fully-clothed dip in the pool, an exhausted Hussein lounges on the terrace, staring out at the hopeful, distant lights of Tehran. Reality—and the fatal heist—will intrude come morning.

Faintly surreal and suitably morose, the last vignette packs a punch. Hussein’s walk through the apartment has a ritualistic slowness: it evokes the solemnity of a convict’s last meal. It’s not punitive though—there’s tenderness and pathos in Hussein’s longing, given full vent by the wine. Left waiting on doorsteps every night, Hussein finally finds himself invited in, and steps into nothing less than a vision of earthly paradise. Nestled high above the ground, there’s no place else to go from his perch but down. It’s as if the unexpected glimpse of heaven is the shove that sends him over the edge.

Less didactic than The Circle, Crimson Gold’s dour diagnosis applies to both individual and society. Panahi’s Iran is a deeply confused and unhappy place. Stuck in the fundamentalist past amid the West’s noisy onrush, Tehran suffers through its dysfunction aimlessly—it’s enough to drive Hussein’s rich customer, an emigré recently returned from the U.S., to berate it as “a city of lunatics.” Keeping order is the heavy hand of the state, so omnipresent in The Circle. Punctuated by midnight arrests under unspoken charges, the movie depicts the law as a faceless actor bent on denying its subjects happiness.

And what the state doesn’t withhold, society does. “He didn’t have to look at us like that,” a wounded Hussein says after their abbreviated shopping trip to the jeweler. Unkempt and inarticulate, he’s an emblem of dispossession and class resentment. The final outburst of violence, in its ill-conceived crudeness, seems as much a get-rich scheme as it is a desperate slap at the world’s indifference. Slumped against the bars of the jeweler’s store, in a jail of his own making, Hussein is more than just a prisoner: he’s become a zoo attraction as well. As curious bystanders stop and peer in, this last catastrophe plays like a cruel punch line. The invisible Hussein, now bereft of hope, finally has everyone’s attention.