Reviews

When a friend recently noted that my taste in horror flicks tended toward the “grim and serious,” I had to balk—we’re talking about horror movies after all! But I may be in a minority by virtue of taking that grimness for granted.

Tim Burton is one of the better pop-circus ringleaders and more unremarkable artists that American movies have to offer; evidence of both tendencies is much available in his Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

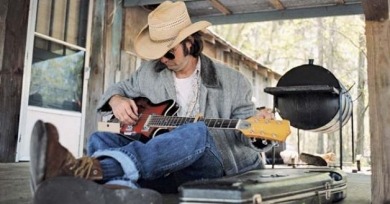

As I am both a fan of the music of Jim White and a junkie for all things Southern, news of the travelogue Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus elicited from me a cry of “Now that’s my kind of movie!”

Gone are lingering shots trained simply on the sight and sound of unrelenting falling rain and, in place of long stretches of naturally foreboding silence, this rendition inserts bad mother-daughter bonding banter.

How better to make a movie on love, trust, and desire than by example? Yet Tropical Malady’s plunge into the jungle asks us to set aside our own narrative desire for the romance between the two young men to work out on its slow but sure naturalistic path.

Ultimately, Nolan’s film is a triumph of casting: fan-types have been clamoring for Christian Bale since American Psycho. Because really, what is Patrick Bateman if not the slightly crazier, NC-17 version of Batman: a fantastically endowed sociopath-playboy in thrall to his deep-seated obsessions?

The Star Wars brand name fills the screen then recedes into the cosmos, trailed by that famous crawl of backstory, while John Williams’s familiar score oversees the proceedings with the pomp of a graduation recessional.

Considering that politics and aesthetics are inseparable, it’s curious how difficult it can be to not read the one as an inherent reduction of the other rather than a potential expansion.

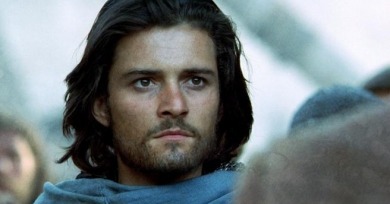

No one does pompous like Ridley Scott. Where a film of average self-importance might look down its nose at an audience from time to time, a Ridley Scott vehicle does so while conducting massed woodwinds and coordinating a rain of individually picked rose petals from the heavens.

Brothers is deserving of accolades for rethinking the genre but is, sadly, unlikely to garner anywhere near the same amount of fawning adulation as that which greets high-profile macho counterparts like Saving Private Ryan.

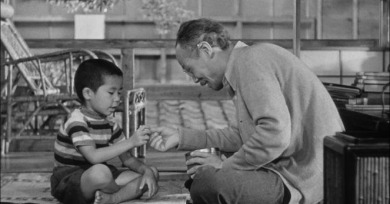

Would it be heretical to suggest that the early films of Yasujiro Ozu are richer than his canonical work? This isn’t to impugn the later films, of course: the mature Ozu is one of the unquestioned glories of the cinema.

What’s left is just lowlife burlesque aimed squarely at folks who lap up real-life tough-guy ‘toons like Bukowski and bird-flicking, posterized Johnny Cash, a straight whiskey, no chaser hard-living fantasy for big kids who think 50 Cent’s too black.