Chewing the Fat

by Suzanne Scott

Super Size Me

Dir. Morgan Spurlock, U.S., Samuel Goldwyn Films

My first solid food as a child was a Filet O’Fish from McDonald’s. It is, to this day, the meal I order every time I pass beneath the radioactive-french-fry-colored glow of those beloved golden arches. If forced to guess, I’d say I’ve consumed at least a few hundred of those puppies over the past two decades. That is to say, I’m no hippie vegan type. I’ve never bothered to read Eric Schlosser’s manifesto for aforementioned hippies, Fast Food Nation, though I have heard countless friends spout its teachings like the religious zealots I make a point of ignoring in public places. To top it all off, I reside in Los Angeles, the land that carbs forgot, and where most people, sadly, think of “Crunch” as a gym rather than a candy bar. I am, in short, the kind of person that Morgan Spurlock’s pop-doc Super Size Me aims to enlighten.

I wish that I could say “mission accomplished,” but my mouth is currently full of fried fish goodness. Consider it a perverse act of junk food solidarity from me to you, Mr. Spurlock. May it bring you fond memories of Day Eight.

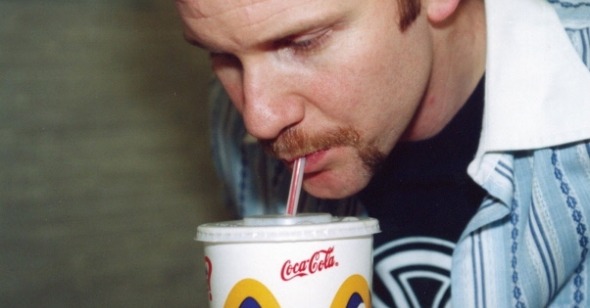

A crowd-pleaser at the Sundance Film Festival and given credit for single-handedly strong-arming Mickey D’s into ridding themselves of their Super Size menu (say what you will about the chain, but you can’t accuse them of cause-and-effect false advertising on that one), Super Size Me does for Big Macs what Bowling for Columbine did for Remington Rifles. And, clearly, the rabblerousing spirit of Michael Moore haunts the entire piece, though Spurlock’s amiable presence and doofy handlebar moustache make him a slightly less commanding ringmaster. So affable, in fact, that Spurlock inadvertently undermines his own manifesto with his Bueller-esque persona—case in point, it’s hard to take potential liver failure seriously when you’ve seen the same man not two weeks prior jokingly refer to his McStomach Ache and McTwitches after his maiden Super Size voyage.

From our introduction to the film’s conceit (tossed out in glib, post–Fear Factor “triple dog dare” rhetoric, Spurlock standing stoic in the middle of a bustling Manhattan street as the music swells) to the experiment’s inevitable conclusion (am I spoiling anything by telling you that eating fast food three times a day for 30 days straight ain’t healthy?), Spurlock serves as a gluttonous guide to all things that fall under America’s “bigger is better” mentality, from McDiets to McConsumerism and the interdependent web of fries that connects them. While this is certainly a novel and entertaining way with which to knock home a point or two concerning our own denial of our “toxic environment” (posing fat as the new tobacco, and our car culture as obesity enabler supreme), Spurlock seems to enjoy testing the limitless boundaries of junk food culture more than he does actually exploring their intricacies.

The orgies of fast food consumption through which this commentary is threaded are tempered with doctor visits, each one more disturbing than the next. More intriguing than the data itself, the three specialists tracking Spurlock’s progress slowly morph from a state of bemused participation to a mildly panicked retreat, visibly fearing malpractice comeuppance for their mere association with the endeavor. But perhaps even more shocking than Spurlock’s physical decay (which was all but guaranteed from the outset) is the emotional decay that America has seemingly suffered in the name of economic prosperity. If Spurlock’s human lab rat routine works perfectly in one regard, it’s in his ability to infuse a sense of forgotten humanity into an industry whose battle cry has always been “it’s not personal, it’s business.” And, fair enough. Capitalism isn’t going anywhere, and Spurlock isn’t foolhardy enough to insinuate that it might. Instead, he chooses to exemplify his meta-diet with micro examples of the effects of this vicious binge/purge cycle on everyday lives. These poignant interludes—the one that comes quickest to mind is that of an overweight teen and her equally plump mother quietly bemoaning the lack of funds get on the Jared plan and purchase two Subway sandwiches a day—unfortunately are crammed amid far more verbose and ultimately less striking cries against the indomitable giants of the industry.

Super Size Me, in the documentary tradition, is precisely what it is critiquing, a piece of cinematic junk food. And I say that with the utmost respect. If Spurlock’s objective is merely to entertain, then he does so with aplomb. However, the film’s conclusive call to arms (complete with obligatory pan across a cemetery and bombastic “it could happen to you” admonition) and its meandering construction of blame (Does media pressure nullify free will? Spurlock can’t seem to decide) leaves the viewer with little more than a desire for something a tad more…dare I say it…substantial. Spurlock is no Eisenstein, obviously, but is he is visibly striving towards the same end: political mimesis. And it would be a possibility, had Spurlock’s scope not obscured any viable call for change. As Spurlock approaches the McWorld, with a nibble here and there at the corporatization of school lunches, celebrity endorsement of malnutrition, and fast food omnipresence and accessibility, his stunt ends up merely a last ditch effort to call attention to the effects of the unstoppable juggernaut that is junk food culture. Consequently, what could have been a pared-down examination and proposal of solutions to one of America’s longstanding dilemmas is now a sweeping critique on society at large, the intended connection between “Why is he doing this to himself?!” and “Why are we doing this to ourselves?!” too tenuous to prompt any real action.

Though, Spurlock does come up with one intriguing solution, especially when contextualized in the era of such televisual rubbernecking as The Swan: "Every time I drive by a fast food place, I’m gonna punch my kid in the face." Nicely put, Morgan Spurlock. Pavlov would be proud.