Reviews

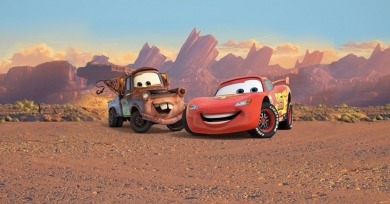

With John Lasseter and Joe Ranft’s Cars, the ever-growing commercial imperatives required to feed the beast that is Pixar have overwhelmed any sense of responsibility towards their audience.

The chance of there ever being a true “director's cut” has been precisely nil since the director’s death in 1985, but Criterion has done as much as anyone could have possibly hoped in collating what's out there and presenting it in a hefty three-disc, one-novel set.

Shot for Fox during noir’s gestation period in 1941, I Wake Up Screaming starts with a silhouette-and-silky smoke backroom interrogation, then quickly abandons such squalid climes for settings more MGM than Warners.

Much has been said about the charm of Singer’s films, especially since he sacrificed the X-Men franchise by passing the buck along to Brett Ratner, whose X-Men: The Last Stand brought the triptych to a close with a resounding thud.

No, it’s not “relevant” at all—how could such a soul-killing journalistic-anemic word apply? Harlan County USA is primary and essential.

Respectable opinions hold that Jimmy Breslin’s 1971 mob farce The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight is a very funny book, and watching James Goldstone’s film of the novel from the following year, you can believe it.

I always find a bit dismaying those moments in globetrotting documentaries when it’s giddily revealed that, centuries of local culture notwithstanding, the kids in these far-flung locales actually just live for Top 40 hip-hop.

t’s boring and full of despicable characters, it suffers greatly from plotline packrat syndrome, and is frustratingly bent on lending credence to stereotypes about Germans’ lack of humor and poor taste in pop music, perhaps, but it’s also fairly derivative.

Winter Soldier centers on a single meeting on a single day in 1971 when the group Vietnam Veterans Against the War assembled more than 125 soldiers in a Detroit hotel to recount atrocities they’d either committed or witnessed.

Robert Altman never makes claims for greatness; each new release portends nothing more than another 100-something minutes of Altman, no larger, no smaller.

But seriously, why isn’t Leonard Cohen onstage himself, performing his own songs rather than these self-serving, insufferable egomaniacs?

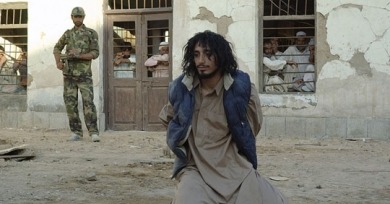

Hey, kids, do you like violence? Well, step into to the multiplex exploitation circuit, circa 2006: flip, Grand Theft Auto nihilism, a bulging pocketbook, and Quarterback-blandsome leading man, Paul Walker.