Nouveau-pauvre

by Leo Goldsmith

Fun with Dick and Jane

Dir. Dean Parisot, U.S, Columbia-Tristar

About halfway through Fun with Dick and Jane, the attentive viewer might start to notice a preponderance of small signs that read, “Gore-Lieberman 2000.” It’s an odd gesture, one that registers neither as a cogent declaration of political alliance, nor as a pointed “I told you so.” And when George Bush appears onscreen, delivering his 1999 stump speech about the “purpose of prosperity” to cable news audiences, the viewer is given another chance to head-scratch. Is this nostalgia for a pre-9/11 world and a boyish, wide-eyed presidential hopeful? A liberal finger wagging at America’s former (or current) naïveté? Or has Judd Apatow’s script just been sitting around for five years?

As a work of recent history, Fun with Dick and Jane toes a rocky path, particularly for a comedy (and a Jim Carrey movie at that). In the movies, the smart money is on the historical epic, where the remote past can be mythologized beyond recognition. Revisiting the recent past, as Fahrenheit 9/11 and The Big Lebowski make plain, is usually an awkward reminder of foibles we haven’t fully outgrown. And so, when we meet Dick and Jane Harper in the salad days of 2000, the only noticeable difference (aside from Carrey’s spiky Matt Lauer haircut and his shiny, three-button, Regis Philbin suits) is the sunny optimism of Bush’s “age of unmeasured prosperity.” Living somewhere in Anywhere, USA (Los Angeles, it turns out), the Harpers are the kind of happy, modern couple who cede parental duties to a Mexican nanny named Blanca and schedule sexual intercourse around the availability of the new Starbucks sampler CD (featuring Sadé). Their grey, prefabricated house sits among the identical houses of their neighbors, each boasting copious bathrooms and a BMW in the driveway. The bubble is intact, and all is right with the world of the upper middle class.

On an oh-so-typical morning, Dick cheerily commutes to his nebulous job at Globodyne, a faceless (and seemingly purposeless) corporation, where he glad-hands clients and makes incomprehensible MBA-speak with his colleagues. For his good services, Dick is wooed by “Corporate” to become Vice President of Communications (or something), and to publicly announce the company’s quarterly earnings on national television. Wasting no time, Dick coaxes Jane into ditching her job as a travel agent and promptly calls the contractors to have a pool installed. Flashing his plastic, toothy grin, Dick soon turns up on a cable news channel to represent his beloved corporation and is summarily grilled into submission by an ersatz Lou Dobbs and an all-too-real Ralph Nader (in a decidedly unflattering cameo). It seems that Globodyne’s execs have been ImCloning around, and have neglected to inform Dick before airtime (or before golden-parachuting themselves out of the mess). Consequently, the corporation’s stock tanks, its employees are left jobless, and, suffering the worst indignity of our age, Dick becomes the subject of an amusing email forward.

In updating Ted Kotcheff’s 1977 film of the same name, Judd Apatow and Nicholas Stoller have lifted whole sequences for the body of their film. But with a dash of contrived relevance, the writers have inserted a little updated material into the setup, even venturing to thank the executives of Tyco, WorldCom, and Enron by name in the end credits, just in case you missed the point. As Globodyne fat cat Jack MacCallister, a portly, improbably Southern Alec Baldwin tries for his best Ken Lay-George Bush impersonation, giving interviews while hunting grouse and telling reporters, “Now, watch this shot!” Whatever its “point” may be, the film finds mercenary motives at the very heart of the American Dream, and it is not long before our Dick, worn down by all-you-can-eat buffets and bathing in the neighbor’s sprinkler, decides to do a little stealing for himself.

Despite the pseudo-currency at its outset, the rest of the film cleaves closely to the original, a forgettable film even by Jane Fonda standards. Here, as in the earlier version, most of the laughs trade in the sort of bland racial and class stereotypes that favor no one in particular—and are therefore available for all of us to enjoy. Like George Segal’s Dick, Carrey’s character endures the humiliations of job-hunting with minorities, is mistaken for an illegal Mexican immigrant by the I.N.S., and makes a couple of one-liners about prostitution before resigning himself to a life of crime. “We followed the rules and we got screwed,” Dick tells his wife, resolving to stick it to The Man by stealing his way back to shallow bourgeois respectability. With their son’s water pistol handy, Dick and Jane graduate from shoplifting Slushees, to knocking over head-shops, to ordering their skim-milk mocchacinos at gunpoint. Before long, the Harpers’ pool is finished, they can pay their landscapers again, and Dick is the envy of every man on his block. But with the clockwork inevitability, the third act finds a repentant (or compassionate conservative) Dick and Jane seeing the error of their ways and resolving to “leave no one behind.”

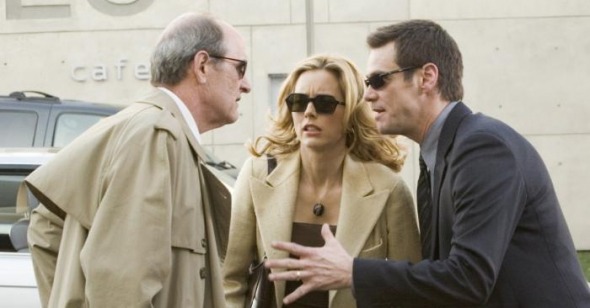

While the film’s stabs at satire remain ultimately toothless and its comedy shamelessly treads that currently chic line of sarcastic racism, the film nonetheless moves briskly enough and has a few inspired touches. For one thing, it’s at least a treat to see an American comedy that doesn’t seem to have been assembled during a drunken weekend and that doesn’t feature a Wilson brother. Director Dean Parisot has proved himself adept at this kind of slick, painless comedy. His 1999 film Galaxy Quest made much of a potentially slight premise, and if Fun with Dick and Jane does not succeed nearly as well, it is largely because it squanders a fine roster of character actors. Laurie Metcalf, John Michael Higgins, Jeff Garlin, Kym Whitley, and even Baldwin (now officially a character actor) appear in woefully slight roles (while Téa Leoni, as Dick’s paramour, is in every other scene yet remains barely noticeable). The only supporting player to get much camera time is Richard Jenkins, whose appearance as a drunken, crooked stuffed-shirt is a nice variation on the actor’s performances for the Coen Brothers.

This means most of Fun with Dick and Jane revolves around the film’s star (oh yes, and producer), Jim Carrey, who here seems relatively underamphetamined, if even a bit haggard. Carrey is starting to show the wear of his 43 years, but he’s still sprightly enough, and for the most part, the film is as surprisingly agile as he is: trim and fast-paced, stumbling only in those perfunctory moments of moral clarity (there’s more to life than WASP culture!), in which the requisite cheerful conclusions (and flavorsome comeuppances) are to be doled out. But here too, the film is mercifully streamlined, without letting Carrey mug or emote for any duration. This is to say that one’s enjoyment of the film turns primarily on Carrey’s performance not merely because the actor is an unabashed comedic ham but also because the film’s pathos for its characters hinges upon Carrey’s status as the prototypical “Dick.” Carrey, the film proposes, is an Everyman for the 21st century. But if, like me, you don’t happen to sympathize with any of the film’s variations on the American Dream, that’s a frightening thought.