Pure Gold

by Nick Pinkerton

Just Friends

Dir. Roger Kumble, U.S., New Line Cinema

Down the movie theater hall, faraway from the din of me-too media shills playing dueling hyperbole over the young cast of Brokeback Mountainâone-trick Gyllenhaal and his million-dollar chin-down brood, Heath Ledger confusing repression and constipation, and frowsy Michelle Williams, with all the kewpie, neo-Shirley MacLaine charm wrung out of herâsome of us caught a look at this yearâs real all-star line up of North American screen players. Ryan Reynolds! Amy Smart! Chris Klein, back from purgatory! And a crossover from the Brokeback set making a very good case to be called one of the best comic actors working today, Anna Faris!

Just Friends had the misfortune of ostensibly belonging to one of the more reviewer-reviled comic subgenres; lacking any sort of critical cachĂ©, its likes are usually thrown to the interns, written off in 48 states by some stooge on AP wire, or dealt âsafeâ pans by grandstanding writersâRoger Ebertâs deadly unfunny review read like an embarrassing public senior moment. A slam-bang slapstick with needled insecurity behind most of its big laughs, the movieâs a just-slightly grown-up version of the gonzo, gross-out romcoms that drained teenage wallets of part-time job money starting in the late nineties; it was even partly underwritten by the producer team of Chris Bender and J.C. Spink, who made their name with that movementâs quintessential film, American Pie.

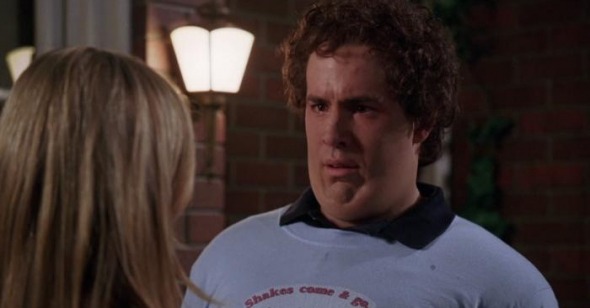

The movieâs prologue starts in true not-another-teen-movie fashion: a house party celebrating High School graduation in the Jersey âburbs, tense with our heroâs now-or-never need to declare himself to That Special Girlâshades of Canât Hardly Wait, except that in place of the cloyingly wide-eyed, nattily bleach-coiffed Ethan Embry, the pure-spirited Romantic many Senior-year virgins mightâve liked to imagine themselves as, weâre asked to identify with Chris Brander (suspiciously close to Bender, no?), a permed Ryan Reynolds entombed in a fat suit, lisping through his retainer, singing along to an All 4 One cassingle in his bedroomâthe complete compendium of adolescent awkwardness. Chrisâs doomed attempt to take things to the next level with his gal-pal Amy Palamino (Smart) results in one of those complete public shamings unique to the social bathysphere of High School; it ends with him hopping on his bike and wobbling out of the driveway in complete desolation. The movieâs superb sound design, which later will lend fine Dolby crunch to every crotch-slam, almost buries Chrisâs farewell under his peersâ laughter, so itâs doubly funny when you pick it out: âThis town is full of losers, and Iâm pulling out of here to win!ââfrom Springsteenâs âThunder Road.â

Ten years on and Ryan Reynolds is just plain Ryan Reynolds, the same ridiculously handsome Canuck of Classical Grecian physique whoâd admirably smarmed and popped his intent eyes through National Lampoonâs Van Wilder. Heâs got a great job in the recording industry on the Left Coast now, seemingly endless prospects for emotionally unfettered, noncommittal sex, is the star of his amateur hockey league, and lives one of those effortlessly perfect lives as advertised in Stuff magazine. But when given the job of courting pop strumpet Samantha James (Farris) in Gay Paree for his label, theyâre grounded by a blizzard en route, coming down serendipitously close to his momâs place and stranding Chris home for the holidays for the first time in a decade, where heâs surrounded by people who remember who he used to be, including the only one that got away.

From here the movie skiffs through reunions and near hook-ups, lessons learned, falling-outs and making-ups with remarkable aplomb. Reynolds is very funny, and he does condescending snark better than anyoneâhis stand-by schtick is meandering through a line reading with a vacillating tone before snapping it out, quick and nasty, through an immaculate, clenched smileâbut when itâs time to put that leading man jawline to its proper use, he can seem out of his element; emoting toward the vacuum that is Tara Reid in Van Wilder, our hero disappeared. Not so here: when Jamie catches Chris freaking out in his rental car after heâs unsuccessfully put his âchicks like assholesâ philosophy to work on her, the scene just playsâMs. Smart humanizes the sometimes deadening flip assholism that Reynolds was left to breeze out in last yearâs wallow-in-raunch Waiting. The ultimate complement to the articulacy of Reynoldsâs comic persona is that itâs ready for deconstruction this early in his career. Smart, who hasnât been spotlighted so lovingly since 1999âs wonderful Outside Providence, is warm and appealing enough to ground not just him but the maelstrom of screen violence around her; whenever someoneâs breaking their back for our enjoyment (which is often), her reaction shots are enough to keep the movie from going over completely to Three Stooges masochism.

Faris, playing an amalgamation of interchangeable, tuneless pop tarts thatâs not so far afield from her dipshit starlet in Lost in Translation, riffs on the contrast of her sugary blonde cuteness and complete lack of any shame in a fashion long admired by connoisseurs of the Scary Movie franchise. Her shrill diva, a catalog of everything vile and vain that we like to imagine stars as, deserves mention next to Jean Hagenâs Lina Lamont in Singinâ in the Rain in the Grotesque Caricature hall of fameâitâs that good.

What really makes Just Friends, though, is the detail work; every scene in the Brander household is so no-frills perfect, as the family slips into familiar relationships like an old holiday sweaterâReynolds keeps a great abusive rapport going with Chris Marquette as his kid brother Mike (âYouâll always be fat to me!â)âthe hand-off of a holiday cookie accompanied by a sullen, obligatory, but true âI love youâ competes with any number of moments with Julie Hagertyâs brittle-grinning, pill-hazy mom for the movieâs comic apex. And when Chris and Amy go for a drive, popping in a mix tape from â95 (âThe Summer of Likeâ), anyone accustomed to the easy âHey, I remember thatâ lowest-common-denominator pop-culture gags that pollute contemporary comedies (or, in the case of Dodgeball, are the entire comedy) might be ready for a groaner, but weâre in good handsânext we see of them, theyâre grooving to the techno theme from Mortal Kombat! A certain Reverse Shot editor laughed for a full five minutes.

Director Roger Kumble, who should hold a place in the heart of any late-nineties multiplex-goer for the gilded accretion of sleaze called Cruel Intentions, manages to synthesize saccharine and slapstick in a much more fully-integrated way than his own waste-of-Selma-Blair The Sweetest Thing, or even The 40-Year Old Virgin, which just seemed hard-up for a laugh in deciding to catapult Steve Carrell through a billboard at its finale âneither tendency betrays the other here, nor does the movie ever feel like bipolar pandering. This movie just takes place in a violent world, thatâs all.

Thereâs nothing new under the sun in Just Friends: it has its shades of Romy and Michelleâs High School Reunion, and the whole East Coast authenticity vs. L.A. bullshit thing is plenty shopworn (though itâs rarely expressed as well as âYou're Hollywood, you date models  he's Jersey, he skis in his jeans!â). But the movieâs primary source of comedy is profound, and essentially the same that drove another of this yearâs true knee-slappers, The Squid and the Whale: the gulfs between self-perception and personal reality, and the pratfalls we take into them. Pepper this with a lot of literal pratfalls, very hard blows to the face, torso, and genitals, and youâve got one for the ages.