“This Ain’t No Goddamn Vaudeville, Motherfucker”

by Nick Pinkerton

William Eggleston in the Real World

Dir. Michael Almereyda, U.S., 2005

Stranded in Canton

Dir. William Eggleston, U.S., 1974/2005

Of late there’s been no shortage of documentaries dealing with culturally marginal artists with significant cachés of cult reputation: recluses such as mole-like compulsive sketcher Henry Darger (In the Realms of the Unreal) and fretboard-strangler Jandek (Jandek on Corwood), lout beatnik Chuck “Buk” Bukowski (Bukowski: Born Into This), and bubblegum bums from Queens, the Ramones (End of the Century). From a distributor’s standpoint these flicks must have an obvious allure: they as good as guarantee box office from an entrenched fan base, and the critical reception from hip city papers is more lenient than not—it’s tough for culturati critics to fault a filmmaker for trying to draw more attention to a worthy body of work, even if the medium doesn’t add up to much more than a 90-minute advertisement. It’s an issue of the product taking precedent over the promotion.

Where these films break down, most often, is at the problem of how to approach the subject for a prospective audience—operating with the assumption of familiarity alienates neophytes, but too much 101-level recap is redundant, remedial stuff for established admirers. Perhaps the most concise criticism of William Eggleston in the Real World, profiling the Tallahatchee County, Mississippi-bred artist widely accredited for legitimizing color photography in the high-art world, is that it errs heavily toward the latter. Almereyda’s movie does formulate a close-up, cohesive portrait of Eggleston the “character”—a guarded-to-the-point-of-inscrutability man of aesthetic obsession and well-nurtured vice . . . it’ll make a fine teacher’s aid in an Intro to Color Photography class, and I hope it helps put a few dollars into the coffers of the Eggleston Artistic Trust, but the project feels like a dutiful briefing, taking just enough time to tick off all of the subject’s irregularities and form a neat, complete picture: his analytical reticence, his infidelity, his homey regionality, his owl-browed opacity. It’s concise and articulate enough stuff, flavored with a dash of dithery analysis, though I can’t help but think the film would’ve been richer for introducing the oppositional, even contradictory biographical counterweights of Eggleston’s life: his theoretical articulacy (Eggleston notched a tenure teaching at Harvard), his fidelity (the circumstances of our subject’s marriage are given a treatment so cursory as to be more polite than intriguing), his cosmopolitanism (he once lived in NYC’s Chelsea hotel while dating Warhol Superstar Viva, and has countless friends in the worlds of pop and art), or his dandyism (the photographer cultivates his image more than Almereyda seems willing to give him credit for—he allows himself baffling sartorial affectations like a silk Chinese scarf on a trip to a Memphis BBQ pit).

What’s the real subject here? I’m not sure it’s art—some of Eggleston’s most famous photos are reproduced onscreen, but, like the rest of the shitty digi-video movie, they look crass, bleary. I can’t imagine a screening of Almereyda’s Eggleston movie having the same revelatory effect on a non-initiate viewer that thumbing through the photographer’s Los Alamos collection could. And a cogent argument could be formed that Steven Shore was every bit as essential a figure as Eggleston in the establishment of color photography in the Seventies—his oeuvre is certainly a more perfect representation of the quotidian quality that Almereyda attributes to the man from Memphis, whose most famous snapshots are too full of romantic decay to ever seem really everyday—but Shore is now tenured faculty at Bard University—booooring!—whereas Eggleston, still in Memphis, boozes and screws around. Something to bring the cameras running. And though Almereyda goes as far as to title a picture of a nattily-dressed Eggleston at the opening of his 1976 solo exhibition as “not your average tortured artist,” his film seems foremost preoccupied with painting its subject as something very close to that; if not tortured than troubled, cryptic, unusual—which is fair, Eggleston’s all these things, but I’m not entirely comfortable with a movie that’s hitched around reinforcing this one thing that maybe too many people know about Bill Eggleston: “I hear he drinks.” Almereyda’s movie can’t stand up to the gold standard of the weirdo artist biopic, Terry Zwigoff’s Crumb, crucially lacking as it is in that film’s sense of inside-out sympathy. The filmmaker may huddle his camera close in a booze-bleary after-hours gab between Eggleston and a younger, lollipop-twirling girlfriend, but he never seems truly complicit—more a breath-holding watcher thrilled at catching a Great Southern Boozebellied Eccentric in his natural environment.

It’s no fun to knock Almereyda’s movie; whatever compunctions I might have, he’s rendered Eggleston lovers an invaluable service. Footage of the photographer in the field is as precious and singular a document as watching the star of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Mystery of Picasso jot across the frame, though both titular artists are far from their most potent work in each film, and Almeryeda’s cutting between the photographer’s snapping shutter and his final photo is certainly a goofier and more intrusive firsthand look into the creative process than Clouzot’s widescreen canvas. And something in the whole exercise feels awfully reductive—I imagine a few critics will find bravery in the “warts-and-all” approach, but how much braver, if even less bankable, would it have been to make a movie that only looks through Eggleston’s camera, not behind it? How much more singular and surprising to make a movie in the footsteps of the photographer’s quiet, stolid son, lugging equipment for his old man? As near a mission statement as William Eggleston has ever given is his credo: “I am at war with the obvious.” Pity then that Michael Almereyda’s movie is exactly what I’d expected.

*****

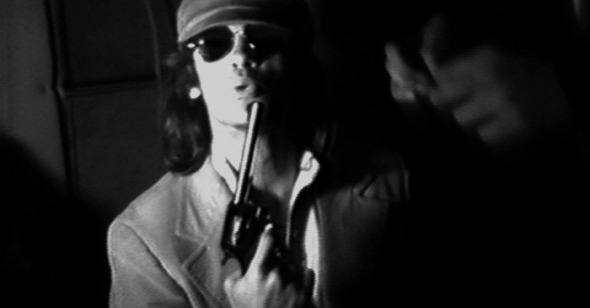

Now, d’ya really wanna ride with Billy Eggs? Ah mean, are ya down, brother? Well why the fuck didn’tcha say so, man? Get in the fuckin’ car! If it’s the more picturesquely seedy side of the Eggleston legend you’re looking for, a far more effective point of entry is offered in Stranded in Canton, a collection of Eggleston’s nocturnal Memphis exploits shot in 1973-74, in black-and-white night vision, on a primitive reel-to-reel SONY Porta-pak camera jerry-rigged with a set of prime lenses. Culled from 30+ hours of footage by Eggleston and Robert Gordon into a 77-minute presentation, Stranded saw a belated premiere of sorts at the 2005 Toronto Film Festival (introduced by Larry Clark!), a supplement to William Eggleston in the Real World’s unveiling. Coinciding with the showing of Eggleston’s black-and-white infrared “Nightclub Portraits” from the same period—and starring much the same cast of characters—at New York’s Cheim & Reid gallery, the film’s since been making festival and one-time screening rounds and may be on its way to a museum basement near you.

Stranded is a ramblin’, howlin’, bender of tape from “back in the days when everyone liked Quaaludes,” to quote from a contemporary Eggleston’s explanatory narration, which intervenes over the footage to identify the drifting cast of characters with drawled anecdote. This technique gives an orienting point of reference that’s handy for fastidious followers of the photographer’s biography (Gordon is one) but which necessarily muffles the great, tactile there-ness of the thing as an artwork. Pulling up close on his subjects, the cameraman stumbles loosey-goosey through honky tonks and julep-sipping, badminton-playing parties of landed gentry, Krystal burger franchises and hotel lobbies, latching onto flushed faces with a lucid tenacity. These tapes are rumbling with messy, shit-faced life—a horse-faced hipster cowboy, “basically a bank robber,” hammering out blues guitar; Lady Russell-Bates Simpson, “the transvestite who makes a travesty out of being a transvestite,” tweaking his/her tortured bleach job and absolutely nailing dive bar-glamour (“That’ll cost you $2.50 extra—remove yourself from my presence”); and always on the periphery, keeping off the center stage of scenery-chewing, fucked-up monologues, a revolving cast of improbably beautiful, doe-faced young women opaquely looking on. The camerawork lacks tact, leaning into zippers and breasts, hanging off every riled-up aria of raisin’ hell, clutching onto unwilling subjects; the material moves between tenderness—Eggleston’s hypnotized-looking children, a girlfriend in giggly intimacy—and grotesquerie—his burly boho buddies acting the fool for the benefit of Eggs’ new gizmo. The only real connective tissue is the nonsense refrain of the title: “Stranded in Canton,” which seems to slur through a dozen pair of wet, loose lips during this roundelay of partying.

“I’m not so fond of the geek scene,” interrupts our narrator, after two one-upping hell-raisers outside a bar have each pried the heads off of a live chicken with their teeth, then quaffed from the bodies’ spurting neck stumps, “It was nothing nearly as personal.” It’s an unusual statement, but essential instruction to the viewing. The “geek scene” implies a separation of spectator and spectacle, the freak and the normal—it’s an exchange that’s invalidated in Eggleston’s Democratic sideshow, where everyone—young and old, queer and straight, black and white, all seemingly at least three drinks along—constitute a glorious geek scene unto themselves. At first glance Stranded’s stars seem the sort of tweaked hilljack hippies, all lycanthrope facial hair and no middle-class self-censoring mechanisms, who crashed free love and sent the more pampered “open minds” scurrying for job security 30 years back—think cracker-barrel Mansons. But though a barstool heckler calls out the cameraman as a “posing asshole,” Eggleston’s circle of subjects ain’t just out-of-it provincial grotesquerie waiting to be gawped at by the shuddering artiste (ahem!—Gummo); any accusation of exploitation probably says more about the accuser than the cameraman. Well-spoken all and druggily articulate, this bunch are a game pack of self-styled outsider loonies, posing assholes themselves.

Speaking of which: the movie’s signature scene might be a jowly heap of a man sticking a booze bottle into his bare ass—though goddamned if he doesn’t announce his stunt with the nicely-enunciated warning: “Regardez-la!” The video’s best passages involve stumbling home to baffled relations, moments which positively vibrate with the glee of being high on art and irresponsibility in a straight world. It’s the perfect, audacious resuscitation after Almereyda’s put Eggs through the post-grad dissection. (In the Real World on Stranded: “The sense of psychic disarray, intimately glimpsed, is both exciting and dismal.”) Stranded in Canton is a wonderful smart-playing-dumb remembrance-of-beers-past that’s all riled-up, rapturous, and packing a desperate Friday night load in its balls.