Reviews

Frank Tashlin poked fun, some would say too slyly, at the infantilism of an earlier, atomic age of super-sized culture by working in its idiom.

Imagine if David Lean had awakened one day and announced, “I want to make the best damned blaxploitation flick ever.” Would that be any weirder than seeing Zhang Yimou’s Hero for the first time?

It’s the film’s delirious sense of anxiety, born out of the confluence of faltering masculinity and powerful female sexuality, that propels its farce forward, and perhaps that’s why Rock Hunter is so interesting to watch today.

In its closing moments, Almodovar announces (though he’s made it clear long before) that All About My Mother is a film about acting, about women, about acting like a woman, about drag, about mothers, about acting like a mother.

Until a major retrospective in late 2000, Italian filmmaker Valerio Zurlini was largely unknown in the U.S. and, by all accounts, wasn’t particularly renowned even in his homeland.

In the end, it’s fitting that most of the discourse surrounding David R. Ellis’s Snakes on a Plane, both pre- and post- its rather modest opening, will focus on the people-powered internet movement that thrust it into the limelight—the film itself isn’t much to speak of.

Oliver Stone has always served as a whipping boy for the mainstream press—“outlandish conspiracy theories!” is still muffed about whenever his name pops up, as if he had exclusive rights to JFK’s not-very-outlandish-at-all suppositions—much in the same way that mentions of Spike Lee or Michael Moore are met with casual eye rolls.

As the sixth and final week of MOMI's well-stocked overview of Frank Borzage's career arrives, it's worth taking a look back to survey the terrain that's been covered so far.

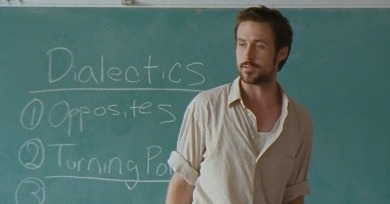

Half Nelson is the same old Indiewood drama with some extra surface noise both narrative and visual: while changing one’s perception of the old teacher-student mentor relationship and the problems of a crusading educator in his mission, it’s still just a bit of low-stakes liberal hand-wringing.

Now that Pedro Almodovar has spent close to a decade working in his idiom of dark, fraught melodramas, it’s easy to forget the vitality of his early films.

His noble poor are so over-endowed with decency that they have to go out of their way to deprecatingly hide it.

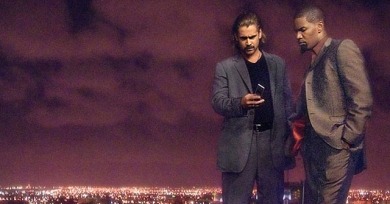

Everything on Michael Mann's film and television resume predicts the exact Miami Vice that he made, which isn't to say that it's his masterpiece.

Vice and virtue may not be ideals that have survived quite intact into this century, and too much of how the critical community tends to think and talk about Borzage already highlights his distance, his antiquity.

The outsized critical gangbang which met the release of M. Night Shyamalan’s Lady in the Water bespeaks of a community of writers gripped by the worst form of pile-on groupthink imaginable.