Reviews

Fincher must have realized Panic Room exhausted the most contrived and stylized extremes of his cat-and-mouse mindfucks, because Zodiac marks an abrupt change in the director’s sensibilities.

Relying on an oddly herky-jerky motion that, within one shot, slows down each thwack and slice to a crawl and then speeds up those moments in between so that we can jump from one death to the next without “dead time,” 300’s fights are just so much faceless, tuneless carnage.

Philip Gröning’s new documentary film, Into Great Silence, is not for everybody. It is, no more nor less, what it purports to be: a nearly three-hour film about monks with almost no speaking, music, narrative, or commentary.

Is Exterminating Angels an apologia? A mea culpa? Are the confessions we hear, some of them seemingly from the pages of a Penthouse Forum, getting at some sort of truth—or are they the eager-to-please buncombe of unimaginative auditioners?

The Number 23 is the best kind of guilty pleasure: a psychological thriller that does absolutely nothing to make you take it seriously.

Tarr’s films are exhilarating, and to describe the work of an—ahem—leisurely filmmaker like him as “A Cinema of Patience” is yet another instance of the impossibly poor linguistic framing that helps keep foreign films from reaching wider audiences.

What Is It? is at once less gratuitous and more insipid than anybody has given it credit for: while Glover’s purpose is wholly sincere and even somewhat brave, his approach is totally wrong and his directorial skills remarkably insufficient for such a provocative task.

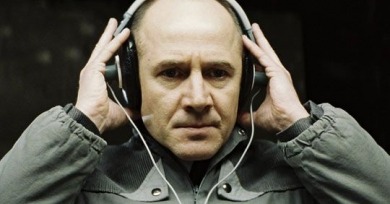

An art-house hit in its first couple of weeks of release, the Academy Award-nominated The Lives of Others is a fitting coda to a movie year that was defined by the ascendant middlebrow.

Bouchareb’s essential aim is to detail the conditions under which Algerian, Tunisian, and Moroccan Muslims fought and lived in the Army.

The Wayward Cloud feels like Tsai’s least perfect film . . . and also his boldest.

I doubt that anyone will ever match the balanced stridency and sentimentality that Jonathan Richman’s song “Give Paris One More Chance” manages as a bursting, corny catalog of everything right about “the home of Piaf and Chevalier,” but Avenue Montaigne takes a crack.

There’s something dubious about a director paying overt homage to his influences, whether it’s Gus Van Sant’s tiresome shot-for-shot Psycho exercise, or Todd Haynes’s subtext-made-blatant Douglas Sirk "update" Far from Heaven, which must have made many ticket-buyers wonder “Would I be better off saving a few bucks and renting All That Heaven Allows?”

Love on the Ground’s progression is some stumbling version of art imitating life becoming life imitating art as the play (built on life) bleeds back into the relationships of the new performers