Michael Koresky

Unlike Duel, the film feels very much like the television movie that it is, and not in small part because of the claustrophobic nature of the story.

While one would like to embrace Sugarland for what seems like modesty (at least in comparison to the grandiosity of his upcoming fish tale, and seemingly every movie after it), its aimless folksiness doesn’t become its director.

Poltergeist, which would become one of the defining horror works of its period, was a pet project of Spielberg’s that he brought to MGM during the first pinnacle of his career.

Eight Reverse Shot writers revisit Steven Spielberg’s 1982 phenomenon.

It often feels wildly inappropriate, especially for a film so burdened by questions of racial and sexual representation. . . . it’s also a remarkable work of Hollywood mastery, and its sheer emotional impact makes it one of Spielberg’s great achievements.

It should be re-viewed as a quintessential Spielberg film; it depicts the belief that our choices are at once motivated by a greater power and a distinct set of humane ethics. That Spielberg filters it all through classical Hollywood narrative tropes is wondrous.

It stands alone as Spielberg’s only courtroom drama, and as thus is preoccupied with concrete matters that none of his other films are, in terms both historical (that history is a reflection of a given era’s social institutions) and philosophical (that natural law needs to supersede that of the land and government).

Munich remains resolutely focused on the response to terrorism and on the effects of violence, and not on terrorism itself or its root causes; terrorism is context, justification, flashback.

What’s most wondrous about his latest film is Davies’s subtle recalibration of his source material, Terence Rattigan’s 1952 play The Deep Blue Sea, into a profoundly felt, even liberated, tale of feminine longing.

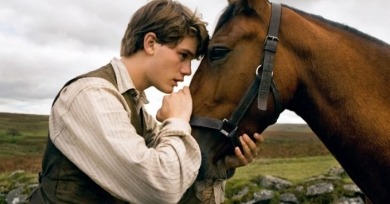

Joey is like a blockbuster version of Bresson’s Balthazar—a patient witness to joy and terror, who only gets dangerously excited when pushed to extremes.

Sexuality and spirituality make for oddly natural bedfellows in Stephen Cone’s gentle, authentic The Wise Kids. Equally generous to all of its characters in a way that seems borderline radical for an American indie, this is a becalmed work about roiling emotions.

It’s clear now from their six fiction features that whatever the Dardenne brothers point their camera at becomes, for that moment, the most interesting thing in the universe.

Swooping into theaters if only to reaffirm that technical audacity can overcome neither soullessness nor a lack of central logic, Silent House is the latest horror-movie-as-filmmakers’-challenge from Chris Kentis and Laura Lau.

So rather than run down yet another list of "fearless" predictions about who will win the big prizes, we thought this year we'd pay tribute to our favorite past Oscar winners: you know, those movies that really make one appreciate the joy and magic of the Oscar season.

Some horror movies send you off into the dark night giddy with fear and pleasantly reeling from revulsion. Others give you a glimpse of something so dark and bleak that you’re left with a queasiness in the pit of your stomach.

There’s really only one thing you need to know about Albert Nobbs: that it was a long-gestating dream project for Glenn Close.

In this follow-up to Marshall’s similar ensemble romcom from 2010, Valentine’s Day, a bedridden Robert De Niro’s dying wish, croaked out of the side of his mouth in the manner of his Flawless stroke victim, is to be allowed onto the roof of his New York City hospital so he can see that precious ball drop one last time.

Everyone seems to understand the basic concept about Martin Scorsese’s biopic of Jake La Motta: that it’s a sports picture blown up into tragic opera, a film about a small (and often, as depicted, small-minded) person who somehow attains mythic grandeur.

It’s a film that is a proclamation as much as it is a movie, a cause as much as an entertainment: this is cinema, it says, don’t let it die.

Steve McQueen’s Shame is the latest entry in what we’ll call the sad sex subgenre. In a sad sex film, partners don’t enjoy each other’s flesh, they rut. They bump uglies. They shudder. Their faces evince no enjoyment as their bodies try to make contact. Sometimes they cry during orgasm.