Reverse Shot Fesses Up

You don’t often find mainstream critics admitting that they haven’t seen The Godfather or Bicycle Thieves or King Kong or Vertigo, but in all surety, they’re out there.

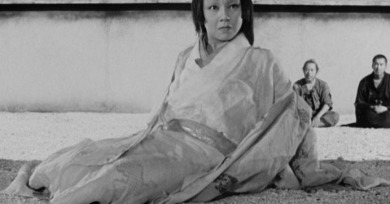

With so much evident historical and thematic import behind it, Rashomon, for the aspiring cinephile, becomes a film about which one will invariably be instructed, in one way or another, regardless of whether one actually gets around to experiencing it first hand.

Disney, however, was no father of mine when it came to Snow White. I have no formative story about snuggling up to the glow of the TV with my coloring pencils or absently humping a couch arm whenever the Queen appeared. (“It was not till years later that I realized…”)

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre reveals—and I can’t believe I’m saying this—how satisfying cinematic death is. It reveals this indirectly, because death hardly occurs in the film. What occurs is death suspended, death delayed, which is frustratingly, terrifyingly unsatisfying.

There’s something I should clarify right away. Though I had not, to my secret shame, seen Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo until last week, I had seen the first four reels, or, more specifically, the upper-right quadrant of those reels and little more, approximately two-dozen times.

The Night of the Hunter is oddly anachronistic and eerily modern. Not surprisingly it was a critical and commercial failure upon its release.

The poignancy of the fleeting nature of wonder suffuses any first-time viewing of King Kong today. Made in 1933 and built on a reputation that has in the intervening years grown bigger than Kong himself, the movie is poised between antiquity and immortality—it is of its time, and yet it is timeless.

If I dutifully labeled Charles Chaplin’s The Great Dictator a “classic film satire,” most people would nod their heads in agreement. Overlong? Maybe. Not quite as tight or as funny as Chaplin’s best films? Certainly. Still, a “classic film satire?” Undoubtedly. But what does that mean, really?

I came late to Lynch because I never had a film-obsessed companion to insist that my life wasn’t complete until I’d seen Blue Velvet or The Elephant Man, which seems to be how most burgeoning film critics are drawn into his peculiar universe.

The Wild Bunch upped the ante so high on what we might call the classical revisionist Western (before knee-jerk irony became de rigueur), that it doesn’t seem possible that anyone could play that particular game anymore.

Does The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance come out on the side of vigilantism or against it? Or is it so easy to separate the two?

Plain and simple, for better and for worse, The Godfather represents the best of what commercial American Cinema has the ability to accomplish.

This is potent filmmaking, and few Hollywood blockbusters of the past 20 years are even fit to challenge JFK in terms of art, drama, and sheer entertainment. But film is also a medium of trickery, and Stone is well aware.

Ever since the heyday of Italian neorealism—the post-facist, postwar films of the forties and fifties—nothing in European cinema has come close in depicting daily life and the struggles of those most abused and neglected by the larger society.