Nothing but the Truth

Brad Westcott on Rashomon

It’s always seemed to me to be a great cocktail party question for cinephiles (that is, if cinephiles did anything as outwardly social as attend cocktail parties): “What is the biggest film—in the fundamental, film studies cannon sense of the word—that you haven’t actually seen?” The question holds interest because it presumes and admits that we all have blind spots; that even for those at the highest echelons of film geekdom, there is ultimately a finite amount of time one can devote to covering all of one’s prerequisite cinematic bases. It’s a zero sum game, after all: that fifteenth viewing of Notorious, which makes you the relative Hitchcock expert in your circle must necessarily come at the expense of never actually getting around to that damned ubiquitous The Magnificent Ambersons, or Caligari, to name a couple of possible examples. And of course there’s an argument to be made that keeping up with the [Kent] Joneses is harder than ever, and will only get harder, as new modern masterpieces are always being added to the list and the proliferation of media in general seems to be increasing exponentially—but then that’s a story for another day.

After finally crossing The Seventh Seal off the list a while back, Rashomon became my next dirty little secret. One can see why Kurosawa’s international masterwork might make a perfect candidate for this particular brand of well-intentioned neglect. Rashomon stands in for a particular narrative strategy with respect to film, but also transcends its specific iteration to signify an idea about narrative itself, whatever the medium. With so much evident historical and thematic import behind it, Rashomon, for the aspiring cinephile, becomes a film about which one will invariably be instructed, in one way or another, regardless of whether one actually gets around to experiencing it first hand. And, having absorbed a serviceable knowledge of it—in much the same way I might be able to sketch out for you the general thematic significance of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time without ever having read a word—it’s reasonable to imagine someone spending his/her actual Kurosawa viewing capitol on slightly sexier options, such as Yojimbo, or that other potential elephant in the room, Seven Samurai.

Reasonable. Yet right around the time I heard The Daily Show’s Jon Stewart refer to the Bush Administration’s “Rashomon-like interpretation of events” in a fairly off-hand manner, as though throwing out a reference to The Brady Bunch, it became clear to me that I could harbor this shame no longer.

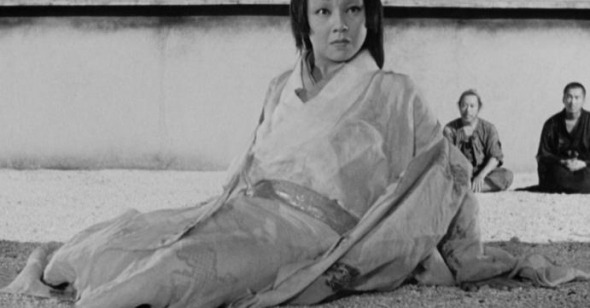

First, what I knew about Rashomon before having seen it: The film was directed by Akira Kurosawa and is set in a historical Japan roughly concurrent with the era of Kurosawa’s other samurai epics. It tells and re-tells the story of a single event—each time from the perspective of a different character—in which a woman, accompanied by a man, is attacked by another man while traveling in the forest. This event is related a number of times, each time from the perspective of a different character in the story. The different versions of the event, as related, are incompatible to such an extent that it is clear that more than one of them is either lying, or possessed of a false remembrance of the event. The upshot of this inability to reconcile these distinctly different perspectives has been interpreted as questioning the very reliability of narrative itself, or put another way, Rashomon suggests that such a thing as objective truth is unknowable. In these terms, the legacy of Rashomon has been essentially philosophical.

The things I couldn’t have anticipated about the experience of actually viewing Rashomon are many. Somehow, in purporting to have already ingested something like the distilled “point” of the film prior to watching it, I was unprepared for the extent to which Rashomon complicates even the “book” version of its ostensible meaning as outlined above, or indeed any unified assertions one might wish to make about it.

Of course in hindsight I shouldn’t have been at all surprised by immense complexity in a work so concerned with precisely such a lack of unity. Yet it’s possible to imagine a film which somewhat didactically espouses the “impossibility of knowledge” (itself a claim to knowledge), then consequently proceeds to abandon narrative efficacy or meaning altogether. In contrast, Rashomon is both complex and committed enough to contain and promote internal contradiction at all levels. Some fifty odd years after its release, the pleasure of watching Rashomon is the pleasure of learning that there exists wiggle room to debate almost any facile assertion or bit of received wisdom about either it’s “message,” or it’s narrative implications.

Far from a testament to the futility of knowledge, or an assertion that existential chaos is some kind of daily norm, the story of Rashomon opens quite classically, in such a way as to suggest that what follows is the telling of a horror story. The horror is the confrontation of the woodcutter and the priest with an astounding aberration in the otherwise seemingly dependable nature of things. Glimpsed through a relentless torrent of rain, they huddle together at the crumbling Rashomon gate dumbstruck, as though staring into an abyss. Only after the commoner’s provocation do they come to life enough to relate their story of irreconcilable truths. Like Conrad’s Marlow aboard the ship-deck at dusk, reminded of that unfathomable darkness, so are the horrors at the heart of Rashomon framed by this quite conventional opening scene.

Although I wouldn’t go so far as to argue that Kurosawa’s film does not suggest or support the main idea which has been ascribed to it—namely that the nature of “reality” or “truth” is unknowable or highly subjective at best—upon watching the film I was struck by a number of elements within the film which seemed to complicate an easy acceptance of those precepts. For example, the woodcutter and the priest seem deeply disturbed by the implications of a world in which everyone lies, or acts only to promote their own interests. The woodcutter has no use for the common “meaning” we ascribe to Rashomon: that there is essentially no ‘truth.’ He knows for certain that the truth is that which he has witnessed with his own eyes. He has not the democratizing distance to see his own truth as one of many. Instead, the proliferation of other versions of the central story means to him simply an abundance of lies and liars. The space between his existential angst (the absence of morality) and ours (the absence of truth) is significant, and has perhaps been under-appreciated by those hoping to tie up the film’s essence too neatly.

Taking this argument a step further, there is enough within Rashomon to support the idea that perhaps there is one truth to this story, and that it is precisely the woodcutter’s version of events. The film certainly favors his perspective by aligning us with him from the very beginning and allowing him to frame the story-within-the-story for us. In this sense, all five stories are certainly not treated equally; they are not necessarily democratized to the point of asserting all are equally true, and therefore all are equally false. It cannot be overlooked that the woodcutter’s version of events has a certain finality, or quality of “laying to rest” the claims made by the others, by virtue of it’s being the last word on the subject. Neither should the rhetorical weight of the woodcutter’s story itself be overlooked: his version is that in which the characters reveal themselves to be the most human, the least self-congratulatory (epitomized by the disparity between the fumblingly inept swordplay recounted by the woodcutter and the skillful swashbuckling on display in previous versions of the same confrontation).

Blindly accepting the Woodcutter’s version has its own pitfalls, of course. The woodcutter’s story doesn’t begin to explain why the wife, the bandit, and the husband appear so convincingly committed to their respective tellings. There is something to the level of conviction inherent in these versions—aided in no small part by their being represented not just verbally, but cinematically—which makes them more than simply well told lies. At the very least, the film suggests the characters seem to believe their respective stories, prompting us to ask why they do. In this way, the film offers what seems an infinite number of jumping off points for interpreting its characters’ actions.

Ultimately, after having finally caught up with Rashomon, it seems far less like some axiomatic assertion, such as “truth is unknowable,” than it does an enigmatic bundle of contradictions, offering only itself and the experience of viewing it as a means toward grasping its depth of meaning. Novel idea, you might say, that to really get at a film, you need to watch it.