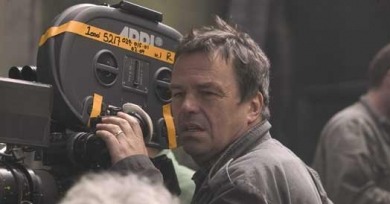

Neil Jordan

"Well, if you’re talking about the current climate, there’s a lack of content in American film because I think people are deeply confused about their emotions, and they don’t regret certain aspects of their own foreign policy."

Breakfast on Pluto, a gleaming smile of hope in a rancid world made up of all different shades of intolerance, is the gloriously openhearted wish fulfillment of The Crying Game—the difference between the two films is as plain as night and day.

Just as Jordan “doubled” the number of heists at the climax, so too does he multiply the analytical distance Melville previously placed between his movie’s world and that of the American pulpsters like Asphalt Jungle and They Live by Night he so carefully admired.

In Dreams, re-watched, looked at any which way, remains a fundamentally miscalibrated movie of rather piquant badness, the work of a preternaturally talented hack, if such a thing can exist.

Magical things always seem to be happening to Jordan’s characters, and so it is here. But The End of the Affair is not about the enchantment of the everyday, but the burden of the transcendent: miracles confound, rather than comfort, when you don’t believe in them.

Things would always work out better for Neil Jordan’s protagonists if they’d simply step in line. Dress right. Act right. Dream right. Talk right. Do what’s right that is, what’s normal and accept what’s given. But his are characters that can’t breathe and conform at the same time.

Jordan has fun with set design and costumes in recreating 1910s and 20s Ireland, and he clearly jumps at the opportunity to construct scenes around intense violence and underground plotting, but he never engages the complications at the heart of Irish identity and patriotism.

Attempting to dramatize Ireland’s struggle for independence without confronting religion is like trying to explain the history of the American South without alluding to race.

With The Crying Game. and recently released Breakfast on Pluto, he demonstrates a penchant for sympathetic portrayals of the sexually demonized of society, and, as such, Interview with the Vampire seems less an anomaly in a somewhat anomalous career.

If you look at the movie instead of the culture’s idea of it, that penis just becomes one among many red herrings. The Crying Game is too complex and elusive, beguiling and beautiful, tragic and heart-wrenching to be reduced to something so banal as a “gender-bending” twist.

We’re No Angels represents the first flowering of solid sense-of-place craftsmanship which would help ground works like The Butcher Boy and The End of the Affair, where the mode of discourse perhaps rests closer to Beckett’s Not I on a relative scale.

Neil Jordan deserves the silent treatment for High Spirits; that any ink should be spilled over this fetid log is a tragedy. Bracing himself for a much-deserved slap in the face, knave Jordan offered excuses and denied culpability, but really he should’ve sent flowers.

Mona Lisa’s story, and its strength, lies in how this relationship develops, but that’s easier said than actually described, because Jordan’s skill lies in taking simple templates and letting loose the forces of genre, class, and gender that shape character, feeling, need.

This is a werewolf film that’s not really a werewolf film at all; certainly not in the way that its early-eighties predecessors were, avoiding horror for a more clinical observation of the myth and its repercussions.

Marked by oblique, carefully composed frames, a general lack of camera movement, an aura of hipster cool, and a flirtation with genre, Danny Boy seems at first like a cross-Atlantic cousin to Stranger Than Paradise.