Reviews

The Act of Killing does not concern itself with replicating reality in the typical documentary manner: recording or preserving historical evidence. After all, since the perpetrators have never really denied their heinous acts, the film is not burdened with a need to prove anything.

After charting the romantic fumbling and interpersonal short-circuiting amongst the post-college set with exceeding subtlety, there’s something undeniably exciting about watching the filmmaker slip out of low-budget naturalism and embrace a wonky side little seen in his previous work.

If Only God Forgives has anything going for it, it’s that it’s clearly the movie that its creator wanted to make. Of course, that’s also mostly what’s wrong with it.

While the limits of Michael Cera’s obliviously adorable moppet act are on full display in Arrested Development, Sebastián Silva’s Sundance-winning Crystal Fairy provides the actor an opportunity to show off the unexpected and fun flip side of the coin: an obliviously assholish millennial.

When one school employee remarks, “I don’t think anyone here is in doubt as to what Lucas has done,” despite a complete lack of evidence, the viewer similarly must be in no doubt as to what Vinterberg has done: he has rigged the game . . .

Rarely has something so lofty felt so leaden as Pedro Almodóvar’s latest, a comedy that mostly takes place aboard an intercontinental flight, stuck circling over the ground because of a landing-gear malfunction.

The free-wheeling nature of Dolan’s aesthetic can result in some dubious decisions, but I’ll take the risks of his throw-it-against-the-wall-and-see-if-it-sticks instincts over the dubious “restraint” seen in too many contemporary films chronicling LGBT experience.

Jem Cohen’s Museum Hours is a strange and rare kind of movie: a narrative feature about how we look at things.

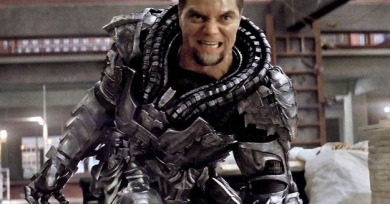

The degree to which the film stands on the shoulders of other more recent science fiction and superhero flicks borders on consumer fraud.

Sergei Loznitsa’s In the Fog is stimulating viewing for those among us still on the lookout for auteurs of serious moral and aesthetic intent.

The most significant quality of Joss Whedon’s modern adaptation of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing is not its black-and-white palette, small self-financed budget, or the fact that the crew shot it in just under a fortnight at his house, but that this is the first film Whedon has directed that he hasn’t also written.

It’s a film which might feel at times like a patchwork of dozens of others, but has a singular quality which transcends almost any comparison: it is built of sound.

You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet proves especially fascinating for both its trapdoor narrative logistics and meta correspondences.

Before Midnight is the first of Richard Linklater’s films charting the ever-expanding romance of Celine (Julie Delpy) and Jesse (Ethan Hawke) that hints at a silence between the lines.