Rubber Soullessness

by Jeff Reichert

Cloud Atlas

Dir. Tom Tykwer, Andy Wachowski, Lana Wachowski

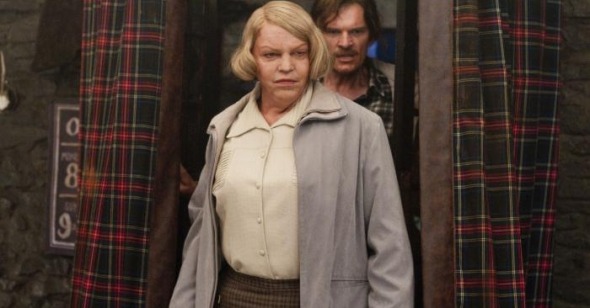

Have you ever wondered what Korean actress Bae Du-na (The Host) would look like playing a red-haired abolitionist daughter of the mid-19th-century American aristocracy? How about Halle Berry as a dyed-blond Jewish trophy wife living in England in the 1930s? Hugo Weaving as a buxom Mrs. Doubtfire-esque British nurse? Jim Sturgess as a near future Korean revolutionary? If so, Tom Tykwer, Andy Wachowski, and Lana Wachowski’s Cloud Atlas might just be the movie for you. (It turns out all of these characters look not unlike one of those Museum of Natural History photo gags that takes your picture and then creates an approximation of your Neanderthal self.) In fact, the filmmakers are so insistent on making sure we’re aware of each new shape-shift that makeup and prosthetics completely smother all semblance of performance. Cloud Atlas is as gaudy a celebration of latex as has ever been committed to film.

The film is also one of the more curious objects to hit wide release in recent memory. It’s an adaptation of David Mitchell’s Man Booker-finalist blockbuster novel of the same name, which is built from six disparate, loosely connected tales that jump between time and genre. Mitchell’s spans the history separating the 1800s-set journals of a young man at sea (“The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing”) and a fireside legend spun in a postapocalyptic Hawaii (“Sloosha’s Crossin’ An’ Ev’rythin’ After”), making stops along the way in pre-WWII England (“Letters From Zedelghem”), San Francisco in the seventies (“Half Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery”), contemporary London (“The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish”), and dystopian Seoul (“An Orison of Son-Mi 451”), with every section focusing on different characters and taking on its own distinct voice and form. In the book, each tale breaks at its approximate midpoint to give way to the next chronologically, until the long “Sloosha’s Crossin’” whereafter the book proceeds to march backwards in time. As the novel progresses, the connections between each segment grow more apparent, the book revealing its epistolary construction in retrospect. Thus, the immediacy of “Half Lives”’ nuclear conspiracies becomes a mystery novel read by the titular protagonist of “The Ghastly Ordeal,” and the tragic romance of the “Letters from Zedelghem” form a component of “Half Lives”’ central mystery.

In the hands of a terrific verbal pyrotechnician like Mitchell, the strict allegiance to the nested doll structure and skillful inhabitance of multiple voices and genres makes for a good read, even if the end result—another we-are-all-connected-so-pay-it-forward tract—is a bit deflating. For whatever reason, the film of Cloud Atlas ditches Mitchell’s most successful structural gambit in favor of chopping the six narratives up into bits and slamming them together at odd ends; if there were an award for “Most Editing” it would be a shoo-in. While this strategy most often ends up wholly blunting any narrative momentum each segment builds on its own steam, the frenetic cutting does at least remind of the power of the editor’s craft—at least one out of every five cliffhanging cuts (there must be hundreds) provides a mild kinetic kick. More often Cloud Atlas’s frenzied dicing highlights false equivalences Mitchell’s book studiously avoided: Jim Broadbent and a wily pack of wide-eyed geezers escaping a forced rest home, when intercut with freedom fighters trying to overturn a dictatorship in future Seoul, reveals the naggingly variable stakes of the source text’s many elements.

The filmmakers’ drastic rearrangement also serves to obscure the most lingering idea proffered by the novel: Mitchell’s Calvino-esque belief in the simultaneous pliability and durability of the written word, and how texts can transcend their own time to create unexpected impact elsewhere. In the novel, the fashion in which each text is transmitted to the next works simply because we read their words, and then the tales of those reading words we’ve recently read ourselves, providing for a richly interconnected experience. On-screen, the links between Mitchell’s tales are downplayed in favor of the visual: highlighting those latex grotesqueries (Look! Tom Hanks is now an innkeeper with a bulbous proboscis!) and emphasizing one of Mitchell’s hoarier devices, a comet-shaped tattoo that shows up on the persons of many of his protagonists. Even though we’re given far more opportunity, thanks to the sheer amount of editing, to consider Mitchell’s segments in juxtaposition, this only serves to accentuate the uplifting notes of what was an often very dark book (the filmmakers even go one further by adding a note of extreme comfort to the end of “Sloosha’s Crossin,” replacing the more ambiguous note of the original).

Cloud Atlas looks and feels all too schematic, eschewing the lushness of the best of Tykwer (Perfume) and the sleek stylishness of the Wachowskis’ The Matrix.(Some day their Speed Racer will likely be recognized as a film speaking a new cinematic language understandable only to six-month-old children and whales.) Despite their film’s surfeit of running, jumping, fighting, and shooting, this trio can’t manage to craft a single remarkable action sequence. This wouldn’t be a total loss if they’d decided to hew more closely to the book’s easy inhabitation of different genres and voices—its best quality. A filmmaker like Todd Haynes would have reveled in the opportunity to make six distinct films in one. The best that the filmmaking Cerberus that produced Cloud Atlas can muster is a kind of rote blockbuster-ized uniformity which irons out all idiosyncrasies.

It’s five novels into David Mitchell’s career, and his most successful outing remains his least ostentatious: Black Swan Green, an autobiographical bildungsroman that captures the protagonist’s 13th year in thirteen chapters, each assigned a calendar month (Mitchell’s obsession with structural games here pays dividends). His worst, the 18th-century Japan-set The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, is a turgid slab of third-person psychological realism that reveals the degree to which his elaborate structural games have covered over a paucity of elaborate ideas. In many ways, this might make the Tykwer/Wachowski alliance a quite appropriate match for Mitchell, given the degree to which works like The Matrix or Run Lola Run—considered with many a solemn chin stroke in their day, both have faded in stature over time.

And yet, for all that, we should be at least mildly appreciative for a film like Cloud Atlas. Even in its ultimate failure, it conceives of a movie experience different than the norm. Unlike the grim visions of Christopher Nolan, it allows no cynicism to seep into its boundaries. It believes unabashedly and unashamedly in “good” and “love”—even if its execution evacuates both of these ideals of any meaning beyond the strictly juvenile. It views humanity as ever evolving but always progressing, no matter how bumpily. And it looks at the universe and the fact of our existence as a miracle worth marveling at, not unlike Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life. Cloud Atlas shoots for the heavens, but its remedial cinematic language trips it up. It’s basically a nearly three-hour pop song that attempts to mold elements of every extant musical genre into one all-encompassing paean to true love and the power of dreaming. And yes, it’s just about as interminable as that sounds.