Reviews

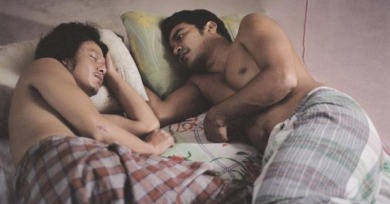

An exception within the still roughly circumscribed realm of Asian-American narrative cinema, So Young Kim’s lovely debut succeeds in blending cultural specificity with generic humanity for a quietly revelatory portrait.

If every administration gets the movie it deserves, Evan Almighty is the most appropriate flop for the long decline of this worst of White Houses.

Lady Chatterley is superficially ripe for the screen: its prose is digestible, its story arc simple, and its action extremely camera-friendly even as it takes up its predecessors’ themes. Yet the book’s notorious erotic journey is, in ways, a distraction.

The flurry of recent press both praising and decrying a new movement in horror filmmaking, dubbed, with tongue planted firmly in butt-cheek, the “Splat-Pack,” shows a determination to justify a cultural black hole.

The biopic, however uninteresting, is among the most schizophrenic of film genres: at the level of performance, the push is always towards verisimilitude—imitation in speech and gait, appearance, and, when the subject is a musician, song—while at the level of narrative, there’s an almost mechanical adherence to formula.

In its detailing of the aftermath of a tragic hate crime in Rheims, France, Beyond Hatred so utterly avoids gratuitous horrors, exploitative grief, and moral grandstanding that those expecting a traditional cine-postmortem will be baffled.

Day Watch may be a lousy vampire movie and an aggressive assault of light and sound, but beneath all that it’s also a brilliant essay on justice, gender, class, and politics in contemporary Russia.

The predictable irony of the horror revivalist bandwagon is that the oft-mentioned imperative to “get back to basics”—which typically means evoking some fantasized notion of “the Seventies”—belies the fact that this new breed of would-be fearmongers are actually doing something quite new and complex.

Besson unambiguously stated that he aimed to capture the “true, beautiful Paris, the one that enthralls millions of tourists every year and we, Parisians, walk past every morning, head down, lost in our personal paradise.”

How apt that the movie is about the ineradicable—yet unrecoverable—past. Henry Fool left us with the image of Thomas Jay Ryan’s title character, a fugitive from the law, making a dash for a plane.

Severance is therefore also, like Hostel, given to ill-advised “chickens coming home to roost” political commentary.

This is a film for the cool, detached viewer who nevertheless craves a powerful emotional experience—just enough distance, no more than will prevent vicarious thrills.

This is what makes the movie so profoundly frightening: though she is willing to commit this heinous act, we recognize that we can, and in fact do, sympathize with her.

There may not be much radically new in Tsai's approach to camerawork and storytelling, yet the film's distinct naturalism feels worlds away from his previous, almost metaphysical stylization. Perhaps it's because he's back home.