Out 1

Jacques Rivette, France, 1971

by James Crawford and Michael Joshua Rowin

This is the second volume of a correspondence that began here.

3

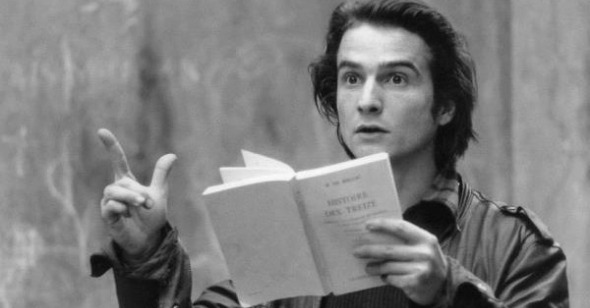

“[I]s it too simplistic to describe Colin as a spectator’s surrogate and leave it at that? What do we make of choice to pose as a deaf-mute and his return to that state at the end of the film? How, for that matter, do we take of the weird behavior of the male (Colin) and female (Frédérique) interlopers? Their logic and mode of behavior is vastly different from anyone else in the film; it’s like they’ve parachuted in from Céline and Julie Go Boating.” If Colin is the spectator’s surrogate in Out 1, then he’s a hilariously flawed and inadequate one—whether that status mirrors or influences the spectator’s own (or both) is the issue. In the first half of the film there are long passages in which Leaud reads the received enigmatic messages, thumbs through books to look up references, writes down passages on his chalkboard and underlines the codes and connections he sees in them. It’s completely ridiculous to show all this, of course, because Leaud doesn’t say a word—the logic of his thought can barely be discerned until he highlights the couple of mentions of “thirteen” in his notes and then meets with a Balzac scholar (played by Eric Rohmer) to gain some insight into what the conspiracy of the Thirteen actually was, and maybe is. And yet these sequences (there are similar ones even after Colin has spoken out) make for more profound representations of cognition in registering the complicated events and ideas of Out 1 (and perhaps events and ideas in all cinematic experiences, or all experiences, period) due to the refusal to go inward and cinematically express states of consciousness.

“How can one render the inside?” Godard once asked, “Precisely by staying prudently outside.” Rivette goes further, filming the workings of the mind by also staying on the outside, recording scraps of shorthand that only completely make sense to the one doing the work. Colin’s surrogate role is complicated, then, by this method of dispersing information through his investigations. Again, the key word is process—Rivette wants to capture and portray human beings in states of becoming, of gradually arriving at an always-doubtful conclusion. When Leaud skims Balzac and comes across a section he thinks pertinent to the Thirteen, that excited action contains as much “eureka!” euphoria, despite the wordless ambiguity and the spectator’s only partial understanding of the plot, as those similar moments when a private eye finally understands the machinations in which he’s caught and now must overcome.

Leaud as a deaf-mute contributes to the power of such sequences, but as I’ve mentioned before, he also acts as a symbolic refusal of language. His return at the end of Out 1to pretending to be a deaf-mute and annoying the hell out of cafe patrons with his harmonica struck me as one of Rivette’s lazier contrivances. Leaud realizes the Thirteen conspiracy is impenetrable, or is just fucking with his head, and abandons the adventure to go back to his day job, of sorts. This wasn’t too dissatisfying a destination for the film’s most likable character (and actor) as much as it was just too obvious an arc. In contrast, Berto’s fatal end left me shaken and mystified. Her blood oath with Renaud (a jerk, but who in Out 1 isn’t?) is really the only triumph of love throughout the entire film, as far as I can recall, but it remains unclear as to whether Berto’s attempt to kill him and last second intentional maneuver that causes him to kill her is because of the insidiousness of the Thirteen, and thus spells the impossiblity of pure individual love in a corrupt world, or because they’re simply doomed lovers. If anything, both of these readings sound too simple to me. Their childlike qualities, and Leaud’s, in accord with Rivette’s and other New Wavers’ interest in children and immature adults as symbols of unsullied imagination, perhaps make them unfit to survive the nightmarish web Rivette forms from the chaos of Paris circa 1970. But considering the multiple layers of meaning of pretty much everything else in Out 1, I just won’t allow myself to accept that as the final summation. Any suggestions?—MJR

*****

Everything you’ve touched on I wholeheartedly agree with, but I’d venture that if Colin/Leaud is “hilariously flawed and inadequate,” then he’s a perfect stand-in, at least for my circumspect understanding of Out 1. The retreat from a fraught and unpleasant reality is certainly a motivation for Leaud’s regressive behavior, yet it’s also commingled with Rivette’s attempt to reclaim, street by street, and corner by corner, an understanding of Paris, a city that has become alien in the wake of the era’s fraught politics. Rivette’s interview from Film Comment is again instructive, speaking of the background city as though in elegy; he says shots of Paris’s landmarks “were inserted…frankly as empty spaces. As a kind of visual silence….” Thus shots where the Eiffel tower peeks in from the edges are denuded of their meaning, a void he tries to fill through Leaud. Colin spends as much time wandering through the streets grappling with his three cryptic messages as he does alone in his room, and thus his understanding of these texts becomes inextricably and reciprocally knotted up with the life of the city. In one of the film’s most delightful notions, whenever Colin reaches an intersection, he flips to a random page from his Balzac anthology and reads a few sentences outloud; his bizarro understanding of the passage dictates to him in which direction he should walk. As the game continues apace, Balzac’s lines are repeated so frequently that their meaning flies away, and Paris, city as fresh cipher, seems to absorb them.

That dialectic between text and city, (or perhaps better thought of as city as text) also arises in Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her, with its unmotivated cutaways to shots of Paris in architectural and cultural flux. Two or Three Things is also a beautiful attempt to understand and document “Her,” but I find Rivette’s more poignant in the weight and wake of the time’s political legacy. In a more reductive sense, Colin is a vehicle through which Rivette indulges in the pleasurable meanderings throughout the city, in order to document its appearance—and so establish a modicum of indexical truth—in a time where social mores were morphing into a murkily perceptible future equilibrium. In a more flighty and fanciful sense, his “play” with the harmonica, as you put it, makes him part of the continuum of people who are tuned into (and seeking) the ineffable, the happenstance, the eternal, and that which lies beyond our perceptive faculties. The little envelopes promising enlightenment Colin passes out to the cafe patrons are stuffed with arbitrary pages indiscriminately chosen from books strewn across his floor; when he describes Pauline/Emilie as his romantic ideal, he calls her “The Infinite.”

My understanding of Frédérique is less coherent, but for a moment can we note that the sublime Juliet Berto’s capricious uglification— dressed as a boy for several episodes she’s made to wear an ugly, shaggy wig that makes her resemble no one so much as Liza Minnelli punched repeatedly in the face—is one of the great travesties of French cinema? There are many moments of self-serving play—such as the time she spends enacting an imaginary shootout against herself in her apartment stairwell—that conform to your refuge-from-reality rubric, and they’re very pleasant to watch, but in final estimation, Frédérique’s a pretty troubling character. By a double virtue, namely Berto’s surpassing beauty and the history of misogyny written into the French New Wave, I think we’re predisposed to celebrating a woman who uses her feminine charms to wheedle money of out unsuspecting prick-thinkers—but as I’ve said before, in a world where everyone seems to be striving to understand something greater than themselves and/or involve themselves in collectives, she’s entirely self-serving and alone, engaging only to put more cash in her pocket. Is it any wonder the only people with whom she forms bonds are a thieving bastard (Gerard) and a man who runs away from the bar at the merest suggestion of talking to his crush (coincidentally also Gerard)? She trades on Emilie’s/Pauline’s fears for Igor and demands money for his undelivered letters, tries to extort money from Lucie (both trading on the conspiracy of the Thirteen, not to divine the workings of some superstructure but for personal gain), and steals from just about everyone else she meets. As such, her startling mid-film beating, at the hands of the dude dressed like Marlon Brando from The Wild One, is deserved, and her shockingly abrupt assassination is the ultimate (if excessive) punishment for her transgressions.

By dint of my experience with his lovely female characters, I don’t believe Rivette is a misogynist, so it seems as though Frédérique’s shooting is the necessary exorcism of her negative energies from the film. Her death allows Out 1 to move forward in the spirit of…of…what, exactly? Towards the end, Thomas is wandering the beach with Lili, speaking of his desire to build another theater collaboration out of the ashes of Prometheus—which, given the spectacular disaster of his previous work, is no certain success. As with the ending of Céline and Julie (apologies for returning to that film, but it is firmly lodged in my mind), here Thomas’s future plans threaten to begin the cycle of aimlessness (and in the case of Out 1, collapse and failure) all over again. So, when Out 1 meanders toward its conclusion, what are we left with? Is it doomed to repetition, or is there hope of moving out of this inexorable vortex, as when Bulle Ogier finally gets in touch with the specter that is Igor?—JC

*****

4

You set things up well there, James. First of all, your characterization of Frédérique as “troubling”—she’s a wrench in the film’s otherwise utopian designs, whether that design exists only as an ideal for those who seek it (Colin) or as a loose contingent given life by its practitioners but also abandoned and trampled on by same (the Prometheus and Thebes players). So perhaps I tried to fit her into a greater scheme by earlier writing, “Frédérique immerses herself in matters beyond her own hand-to-mouth hustling” in connection to Colin’s journey and the theater groups’ dissolution. She’s really an outsider even among outsiders, and that her eventual mate turns out to be Renaud speaks volumes. I agree with you about her beauty but not her beating—I couldn’t help but feel empathy for her at that moment despite her misdeeds and disinterest in illumination, and I would have felt the same even if a far less attractive actor were taking the blows.

I’m glad you brought up the “city as text” idea, which I’ve been meaning to touch upon. The very last shot of Out 1 is of the relatively unimportant Thebes troupe member Marie standing in front and to the side of a statue on a Parisian street-corner. It’s fleeting but unmistakable in importing the “empty spaces . . . visual silences” feeling/concept. It’s also clear this is a preoccupation of Rivette’s—Le Pont du Nord takes place in a Paris almost entirely stripped of iconic reverence and seen instead as a city of construction sites, sculptural monsters, and ghostly ruins. There’s not a little bit of Jean Rouch in Out 1’s scenes of Leaud rebaptizing Paris in the walking poetry of Dada (ending up at Pauline/Emilie’s perfectly named Corner of Chance store) and the victimized Thebes troupe scouring the streets for lottery ticket-swiping Renaud (Marie being one of them, still waiting and waiting at her and her colleagues’ own corner of chance), reminiscent of certain deserted, wandering scenes from Chronicle of a Summer. Throughout I felt the partly distancing, partly utterly absorbing duration of Out 1 a rhythm in which the film kept constantly moving out from some sort of center, not so much in a vortex but eternally approaching zero or infinity without ever reaching that destination, this demonstration of a Zeno’s paradox spatially realized in a geographical sense—starting characters out in closed of spaces (practice rooms, apartments, cafes), bringing them out into the light of day in city streets, and then leaving them off at the ends of the earth (or substitutes of same), by bodies of water like the quais of Paris or the Obade seaside. If Rivette kept Out 1 going for another twelve and a half hours, new rehearsals for Prometheus and Thebes would conceivably take place on a raft floating on the Mediterranean. To extract another metaphorical image out of the film’s potentially endless revelatory material, toward the end of the film, Ogier’s Pauline/Emilie, hands behind her head, stares in exasperation, awe, and slight madness at her image reflected forever in the mirror in front of her and in another behind her. In the constantly reinvented city or the eerily static idyll of the sands, infinity, the eternal return, et al, are still Rivette’s threatening specter and prison. —MJR

*****

Damn, you beat me to it—I had been saving that astonishing image of Bulle Ogier contemplating unbounded matter (her body curving gently, endlessly away to the vanishing point) and the fathomless void (that pregnant empty space beside her) for my last, having been struck by—well, many things really—but mostly because that shot is a literal description, as mentioned in my previous effort, of Colin’s assessment of Emilie/Pauline as The Infinite. I think the image of the Obade beach is a fairly perfect instance of Out 1 moving asymptotically towards both infinity and zero, as it presents the image of a horizon endlessly falling away at the exactly the same rate as we approach it: visually dominant as it sets the limits to our field of vision, but ever remaining just out of reach. It’s also a beautiful metaphor for the precarious boundary states explored throughout the film—agency/inspiration, chance/determinism, structure/randomness—especially in those instances where Rivette films Lili and Thomas at dusk. As the water and the sky become the same color of limpid blue-grey, they form a single undifferentiated canvas with no true boundaries at all. Using the dialectics of opposition is an unsatisfactory way to come to terms with Out 1, which should be thought of as a Möbius strip, where two seemingly disparate sides come together—in a three-dimensional representation of infinity, no less—to form one unending continuum.

In the trail left by Michael’s breathtaking poetry, I’m not sure what else I can add, except that the act of filmmaking itself constitutes an instance of this intangible paradox. Film distils solid matter into celluloid’s chemical reaction; the aliveness and physical fact of being is transmuted into the ephemeral nothing of light and shadow played upon a screen. Yet capturing an image on film sublimates it into something eternal, staving off decay, old age, and the other ravages of time as moments are nestled into an endlessly repeating loop. Cinema is void, zero, totality, infinity. —JC