Reviews

“The name of this land is hell. It is not Mexico, of course, but in the heart.” Thus author Malcolm Lowry cleared the air in life for the inevitable posthumous adaptation of his 1947 novel Under the Volcano.

Upon second viewing, there arises an almost spiritual quality to these sequences, a raw essentializing of the human experience and basic animal necessity that approaches Daniel Defoe’s novel and inspiration.

Films fail for all kinds of reasons—they’re shot poorly, the CG looks shoddy, the romantic leads can’t generate chemistry. Self-sabotage, however, isn’t commonly blamed. But to the extent that Robin Swicord’s The Jane Austen Book Club falls short, it’s hard not to wonder whether that could be the culprit.

Divided into chapters that impose order on Chris’s peripatetic life—a decision that seems in keeping with his propensity to see his adventures through the prism of narrative—Into the Wild takes a nonlinear approach to its preordained destination.

Horror is the most overburdened genre in existence, weighed down with so much symbolic, political, and sociological portent that it’s a marvel when a film can actually get down to the business of being scary.

Throughout Julie Taymor’s new musical, Across the Universe, I couldn’t help thinking how much it resembled a Mad magazine column: “The Lighter Side of the Sixties,” anyone?

David Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises is a failed film. And it fails for a reason which many critics consider banal and irrelevant (a good indication of its continuing truth): the script is Bad.

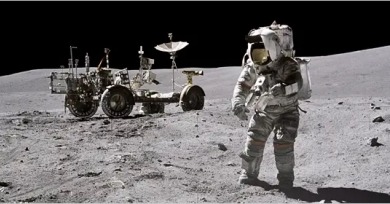

I would be remiss to not admit my own biases toward the subject matter. I grew up on the Space Coast, and it was a common occurrence for me to see rockets launch into the bright Florida sky.

As a straightforward genre picture, it's plodding and dull, but as timely political intervention, it's too diffuse. Elah ends up being about many things and nothing at the same time.

Warner can only hope for cultural amnesia for this to work: Cruising remains a work of unparalleled, unedifying discomfort.

It’s a film of intangible uniqueness, a gentle, almost comforting lyric on the amorality of childhood and the promises of a New Spain emerging from fascism.

Poor acting and directing, of course, offer ample ground for complaint. Yet the greatest offenses of The Nanny Diaries arise not from its gross ineptitude, but in its underlying ethos.

Late one night on a deserted subway platform, a lost Jamie (Erin Fisher), dwarfed by the Tati-like expanse of Brooklyn’s multi-level 7th Avenue F train station, stops the sole nearby traveler, hoodied Charlie (Chris Lankenau) and asks for directions to a local diner.

The drastically polarizing nature of Dumont’s work comes not from any gleeful subversion, or insistence on rubbing our faces in putrescence (arguably Gaspar Noé’s at times admittedly intoxicating work falls more squarely here), but rather from its philosophical origins.