Force of Habit

By Leo Goldsmith

Into Great Silence

Dir. Philip Gröning, Germany, Zeitgeist

For better or worse, most documentaries strive toward the same ends as narrative films: to isolate and faithfully portray characters and, through these characters, to tell stories. Such is the tendency in popular documentary film, from Nanook onwards, and even so-called vérité filmmakers have this goal in mind, though they may seek to achieve it through more subtle (or less visible) means of prodding. This is not an indictment, nor is it even regrettable. It’s merely a (perhaps obvious) statement about what people typically like to see in documentaries: narratives about interesting, charismatic, and often quirky people. This is what documentarians hunt for—the Little Edies and Mark Borchardts of the world—and when they can’t find them, the documentarian often has to fill the role. It’s therefore no accident that some of the more successful recent nonfiction films rely on their makers’ abilities (or, at least, desires) to become their own subjects. Michael Moore, Morgan Spurlock, and even Al Gore have all hit pay dirt by making provocative, often intelligent documentaries on worthy subjects, but their films are more or less overtly about themselves. One is left to hope that An Inconvenient Truth fosters as much discussion about climate change as about the former vice president’s waistline, (re)electability, and putative movie-star glamour.

This is all to say that German filmmaker Philip Gröning’s new documentary film, Into Great Silence, is not for everybody. It is, no more nor less, what it purports to be: a nearly three-hour film about monks with almost no speaking, music, narrative, or commentary. It provides only the most basic contextualization and puts forth no explanation on what it depicts, and although Gröning apparently spent a full six months in the Grande Chartreuse near Grenoble, France, his experience is only present onscreen as a record of what he observed through his camera lens. Like Our Daily Bread, the Austrian filmmaker Nikolaus Geyrhalter’s similarly taciturn documentary about mass agriculture in the EU, Gröning’s film offers only a minimum of spoken and cinematic narration. It strives to be a purely immersive, but nonetheless quite alien experience, as if to question or perhaps simply jettison documentary film’s capacity to educate and entertain, that is, its status as a medium of infotainment. Into Great Silence thus asks an important question of documentary in general: To what extent can or should a documentary function as a means of disseminating information or knowledge about a particular subject, of telling us something? What can a documentary tell us about a subject when it chooses to remain (mostly) silent?

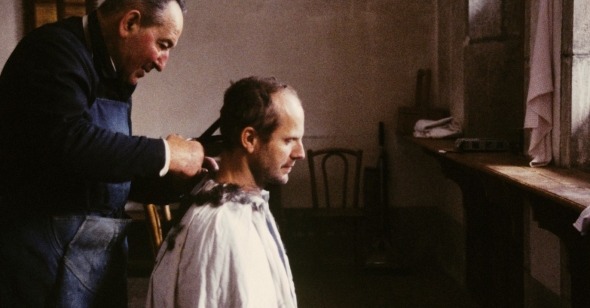

Of course, the “silence” of Gröning’s title is somewhat misleading. Into Great Silence is in fact a rather noisy film, or rather it is a film structured around minute, ambient noises rather than spoken language. If anything, the all but complete lack of speaking in the film serves to emphasize the constant noise—the clamor of bells, the patter of snowfall, the creak of floorboards, and the persistent, ambient hum—that fills that airy space where chatter would otherwise be heard. And when the monks do speak—singing during their nocturnal prayers, a hushed, offhand “danke schön” from one monk to another for the favor of shaving his head, discussions of monastery protocol and tradition on the monks’ weekly stroll in the mountains—the purpose is rarely discursive, but rather drives home the importance of striving towards silence at those times when speech is unnecessary or a distraction. As John Cage found in his anechoic chamber, pure silence is a myth, and the film’s “great silence” is, like much of monastic life, an ascetic ideal to be pursued, but never attained.

Similarly, though the film lacks overt commentary, it is nonetheless structured—and inevitably so. Living among the monks over a six-month period, Gröning is able to capture monastic life as a natural, seasonal cycle, beginning in snowy months of late winter, continuing through the thaw into summer, and ending with the first snowfalls. (This last act offers the rare glimpse of the monks at play, sliding on their backs down the side of a snowy mountain.) In this way, Gröning’s compositions tend to resemble the use of light in paintings by Vermeer or Vilhelm Hammershøi, which use the distinct qualities of seasonal light to suggest a world outside that is rarely seen. Also like these artists, Gröning favors the framing of his subjects at their work and often with their backs to the camera, further implying interiority, introspection, and a closing off of the rest of the world.

Throughout the film’s repetitive structure, there is a constant emphasis on the rigorous structuring of time. The monks never sleep through an entire night, arising in the wee hours for prayer before returning to their beds. Gröning also depicts monastic life as a somewhat more laidback model of industrial capitalism: hours are regulated by the ringing of bells, and activities are timed accordingly. Into Great Silence follows these rhythms closely and repetitively (some of the same tasks are viewed numerous times), and so, like Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, participates in an aestheticization of boredom, forcing an attention to detail and especially to variance in the activities presented onscreen.

While the film does have some recognizable characters (in particular, a young African initiate whose first months at La Grande Chartreuse are sparsely documented), the film resists individuating the monks, instead retaining the overall effacement of individuality so crucial to monastic life. And in its attention to the externalities of the monks’ lives, there is little attempt to depict the philosophical and religious substance of the monks’ internal lives. These are only evoked through the subjects’ example and through occasional (and repeated) onscreen scripture that extols the virtues of material abnegation or complete submission to God. Devoid of lead characters and emotional monologues (save one somewhat superfluous series of comments from an aged blind monk at the end of the film), patience and attention are the only things that Into Great Silence, like the life it portrays, earnestly and continually demands. The spectator is required to submit herself to the subject at hand, as Gröning himself has done, monastically and impersonally denying himself the more subjective devices of handheld cinematography or even, for the most part, long-takes. In this way, the film occasionally seems impersonal (if not actually objective) and almost randomly assembled: a long montage of the monks completing one of their various tasks (feeding cats, shaving each others heads, conducting nocturnal prayers) is abruptly followed by a brief non sequitur of light in the corridors or a macroscopic close-up of plant life or shot of a plane flying silently overhead. The randomness draws the viewer into the rhythms of life in the cloister—it’s difficult to imagine a documentary being any more faithful to its subject.