Features

A Few Great Pumpkins

The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Innkeepers, The Vanishing, The Seventh Victim, Lips of Blood, Repulsion, Insidious

The Thing is not just an unnerving title: by its nature, the enemy, a corrosive alien organism which kills and replicates its prey, has no distinct face or personality of its own—a “conquer and survive” motivation is initially ascribed to it, but it defies any description.

Monument Film sculpture, anders, Molussien (differently, Molussia), Phantoms of a Libertine, Audition, When Faces Touch, Collections, Martina’s Playhouse, From Romance to Ritual, Spying, Confidential Pt. 2, The Extravagant Shadows

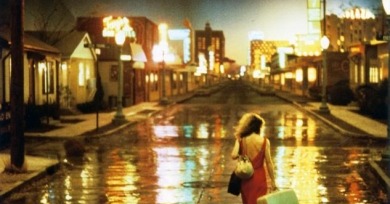

What if the old saying “You can’t go home again” has it backwards? What if we’re invisibly bar-coded to our point of origin, and we’re just spinning our wheels on the map when we try to leave, failing to shed the place we came from?

The way in which Lynch handles that severed ear offers a crucial hint as to how Blue Velvet simultaneously establishes these parallel worlds and destabilizes the boundaries between them.

The couch doesn’t match her house, which is to say it doesn’t match her: pale, delicate, and self-effacing to the point that she practically disappears into the drapery.

A “free adaptation” of Petronius’s fragmented-by-the-ravages-of-time, first-century mock epic, Federico Fellini’s Satyricon (1969) is filled with constant, unexpected laughter.

One of the many remarkable things about Howard Hawks’s Rio Bravo is the way it lulls you into believing you’re just watching an ordinary western. For an unlucky few, this sensation might even remain intact right until the end, but chances are that something in the film will break the spell.

If cinema is a dream, Vertigo is its nightmare.

The famed first sequence of Apocalypse Now not only lays the hallucinatory groundwork for the rest of the film, but it also foregrounds the very scale of the destruction wrought during the Vietnam war.

During his career heyday, thinking small wasn’t part of Coppola’s vocabulary, and One from the Heart easily ranks on any list of filmmaking egotism gone amok.

Juan Sebastian Jacome's Ruta de la Luna, Kenya Márquez’s Fecha de caducidad, Ana Endara Mislov's Curundú, Vero Bollo's Burwa dii Ebo

No less than Merrick’s body and soul, his city is an entity at odds with itself. Graceful drawing rooms and soot-covered cobblestone streets, sparkling theaters and dank sweatshops: London may be on the cusp of the new century, but to Lynch this is still the land of Jekyll and Hyde.

As much as I love watching Days of Heaven, I dread having to write about it. The experience of seeing Terrence Malick’s masterpiece invariably leaves me awestruck and overwhelmed, and gushing is not criticism