Take Four: Color Correct

Yellow wallpaper? Red hair? Green nail polish? Inky black feral dogs?

How do we square this web of physiological impulse, cultural connotation, and ineffable desirability with the almost-cheeky bluntness of Blue?

The toxicity of an entire political system, and of utopias, in general, is condensed into a single image: a black mongrel.

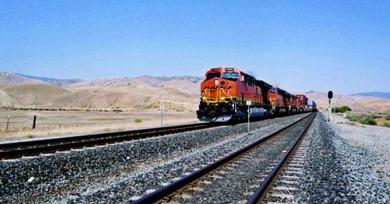

Binding each shot together, across wintry plains, bridges, sun-soaked towns, prairies, deserts, lush forests, and mountains are the unmoving gray rails.

Dominated by beige, khaki and low-key reds, the palette is balanced to the point of being banal, so everything is uncannily uniform.

Everything after the color-flip in A Perfect Getaway begins to resemble Twohy’s previous filmmaking: the shot lengths shorten, the editing pattern accelerates, and he starts playing with slow motion and split-screens.

The shade is confrontational even on first blush, and not much later—after Bob’s wife sends him a trans-Pacific package of barely differentiated carpet swatches—Coppola uses incident to confirm our suspicion that the color in her film is expressly communicative.

Blood, so overburdened in the popular imagination as a symbol for practically anything, is here reduced to something elemental and physical, understood through his new human senses.

This coat, which as the night draws in takes on a burnished quality like wet sand at sunset, is but the most resonant and satisfyingly symbolic shade in a film whose color compositions are, from beginning to end, consistently disarming.

The couch doesn’t match her house, which is to say it doesn’t match her: pale, delicate, and self-effacing to the point that she practically disappears into the drapery.

The sad, and rather radical, revelation of Cabaret is that Sally is not all that interesting, and everything she does, says, and wears—especially that glittering green nail polish—is a reminder of her essential dullness. Her green is a splash of color in a field of gray.

A blue glint of light appears surrounded by blackness in the opening shot of Donald Cammell’s sci-fi/horror freak-out, Demon Seed. This mysterious orb shimmers and expands, until it bursts open and floods the screen in hot light.

The color of the killer’s hair (and complexion) becomes a pigment Hitchcock uses to mold our subconscious feelings about this character’s essential otherness.