Reviews

The book recycles the screenplay, but alters the structure, expands on certain scenes, drops others, restores scenes that did not make the final cut, and introduces a wealth of material that would not have belonged in the film. It is as much a willfully digressive collection of opinions as it is a work of fiction.

Note the staging of his scenes here, how people almost always have some physical object between them as they share increasingly intimate details about their lives, or how that physical object, like a plate of freshly cut apples, can be used to close distance in the presence of silence.

Shot in fall 2019 and originally set for 2020 release, The Forever Purge can’t be taken as a comment on the events of January 6, 2021. All the same, it is a legitimate (and/or opportunistic) ne plus ultra take on the political and social polarization and paranoid atmosphere of the Trump era.

The characters are constantly changing gears to manipulate, to elude, or to survive; the volatile X switches to an African dialect when eager to intimidate but turns smooth and appeasing when under threat, and Zola herself instantaneously snaps from sweet to hostile.

This first foray into scripted narrative by documentarian Heidi Ewing trembles with longing. In this nonlinear, decades-spanning romance about an undocumented gay couple from Mexico, Ewing paints the first blush of love as a neon-lit meet cute, a first kiss beneath a purple dawn.

Neither Koleśnik nor von Horn seek to demean Sylwia or her passion; they depict Sylwia as achieving something like serenity when working out and pushing herself beyond her threshold of pain, respecting her work by recognizing it, first and foremost, as work, as a form of labor that requires discipline and diligence.

If the film ranks among the less refined of the director’s prodigious corpus, few are better suited to depict beachside sexual awakenings or, equally, the rich site where fantasy and intimacy intersect.

What most defines Take Me Somewhere Nice is Alma, a plucky, lusty teenager who navigates sex, death, and lack of money with a self-possession that works as an amulet.

Tragic Jungle is best approached with fairy-tale logic in mind. Olaizola hints at the possibly supernatural nature of the transformation of Agnes by vacillating between the perspectives of the chicleros and their leader.

Funded by a Kickstarter campaign and shot sporadically over a period of two to three weeks on 16mm, Slow Machine has all the features of the rough-and-tumble New York indie, and it wears this vintage shabbiness as a badge of pride.

In his films, Petzold has always suggested the ways that our lives, like city plans, are shaped by historical forces, and also by narrative structures drawn from melodrama and the revenge thriller.

The new Jia documentary may not have the aesthetic boldness of his best work, but it illuminates the proximity of fiction and nonfiction in his oeuvre and doubles as something of a directorial mission statement, highlighting the role of the artist in writing and preserving history.

The filmmaker embraces the emptiness of the landscape. You can sense that David is traversing the same street back and forth, a dead-end town stretching out until oblivion. The muted palette only adds to the sense of simplicity, giving us license to color the narrative with our own readings.

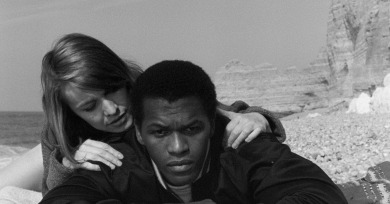

The feature debut from Melvin Van Peebles uses the possibilities opened by the New Wave (jump cuts, pop music, repetition) to explore something profound about race, identity, life, love, the world, and its rediscovery and restoration is an occasion for celebration.