Farihah Zaman

Eight Reverse Shot writers revisit Steven Spielberg’s 1982 phenomenon.

Spielberg’s hackneyed neo-Victorian depiction of pre-independence Indians represents them as either cult-worshiping savages or simple, superstitious farmers waiting for a white hero to come and rescue them.

Films about the experiences of returning veterans have long been on American screens, from 1946 Oscar-winner The Best Years of Our Lives to 2010’s The Messenger (one of several recent contributions to the genre), but writer-director Liza Johnson manages a fresh, surprising approach to the subject matter.

Though Robinson never once appears onscreen, he is nevertheless a compelling and well drawn character. Seeing the world through the images that he created induces a feeling of greater intimacy with him than the traditional cinematic set up of relating face to face ever could have.

With its sweeping views of Tara and its still-shocking mass of injured soldiers horrifically piled up in an Atlanta square, Gone with the Wind is big in a literal sense. But the film is also remarkably intimate, allowing seemingly small things to come into focus as they are thrown against the relentless march of history.

When discussing Miranda July’s second feature film, The Future, many writers have fixated on the relationship between the artist’s New Age-y pixie persona and her art, weighing in on how twee and precious her latest effort is. Relevant, perhaps, but not entirely fair to her work, which has matured significantly over time.

Orphans and primitives both, Bay and Nim approach their respective means of communication—cinema and signing—awkwardly, and from a removal; their resulting control over their languages often suggests clever mimicry instead of true language.

Just as pageantry has long been a part of American culture, so has the National Spelling Bee, a pervasive test of academic acumen despite the fact that it requires a kind of mechanical rigor that has gone out of favor with modern educational systems in this country.

The movie is less a laugh-desperate extended SNL skit than a very funny character study of a woman’s depression and her struggle to get herself back on track. We already knew Wiig could make us laugh, but we didn’t know she was a strong dramatic actress.

African cinema is generally woefully overlooked by the West, and the filmmaking being done in Republic of Chad has been particularly invisible.

It may seem perverse to call for more sex and violence, but in a film that is about barely legal girls living in indentured prostitution—an allegory for the continued exploitation of women—keeping things on the lighter side borders on offensive.

One can only hope that the ludicrous ratings scandal doesn’t distract from Derek Cianfrance’s haunting work itself, which is powered by a simple yet surprisingly effective narrative gimmick.

His form of documentary purism relies on immersion and meticulously edited observation rather than subtitles, narration, interviews, establishing shots, or any of the other tools that most nonfiction filmmakers depend on to construct their stories and propel them forward.

For a good 20 minutes or so, Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor’s experiential documentary Sweetgrass appears to be predominantly about sheep.

neither the off-camera specter of death nor the images of chaos are quite as jarring, nor so viscerally disturbing, as that cat-scratch sound that pierces the harmonious soundtrack.

The title may have been inspired by Shakespeare, but the content of Letters to Juliet is derived from a sticky romantic comedy subgenre: the Italian vacation movie.

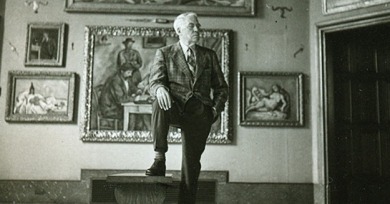

Boogie Woogie attempts to take a brutally honest look at the dark underbelly of contemporary art and the people who admire, sell, and purchase it.

Don Argott’s documentary chronicles the little-known rivalries, politics, and scandals that cloud the history of this monumental collection and its owner, battles that still rage today.

The feature debut from documentary filmmaker Nicole Opper, jumps right into the existential crises of its heroine, Avery Klein-Cloud, dispensing with the introduction of background information before delving into conflict.

As always with Assayas, the camera is not merely a mechanical device, but a natural extension of the director’s eye. His writing is equally intimate and astute, providing us an immediate window into the kind of familial anecdotes and interactions that feel both mundane and revealing.