Framed

by Farihah Zaman

The Art of the Steal

Dir. Don Argott, U.S., IFC Films

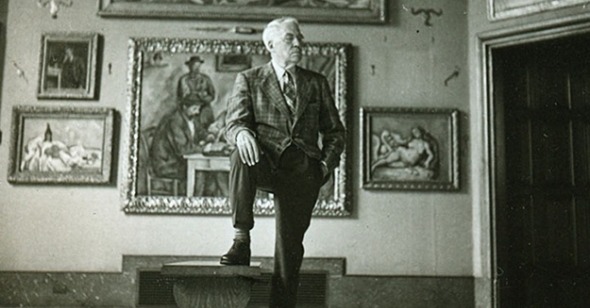

In 1922, a formerly blue-collar pharmacist named Dr. Albert C. Barnes used his newly acquired millions to create a most unusual art museum in South Merion, a small suburb near Philadelphia. With no previous exposure to the art world, Barnes made brave purchases based on his own tastes rather than those of the respected art institutions, acquiring artists unknown or unpopular among elite American society at the time, including Picasso, Monet, Manet, Matisse, and Cezanne. Barnes amassed what later came to be known as the largest and most significant collection of Impressionist, Postimpressionist, and Modernist art in the entire world. Unfortunately, the Philadelphia art scene failed to notice its importance, laughing his one public exhibition out of town, and leaving him with a lasting chip on his shoulder about “the man.”

Even as the value of the collection became widely accepted, Barnes made sure that what he viewed as the establishment would be cut off from it, preferring to save his art for students of the foundation and select members of the public who requested to see it. His will left strict instructions that after his death the collection should not be loaned, rearranged, or otherwise touched in any way. This is when the problems started. As responsibility for the collection changed hands from Barnes’ right hand lady to lawyer Richard Glanton to powerful non profit the Pew Foundation, the actions and intentions of the involved parties became increasingly opaque and questionable and moved further from Barnes’s stipulated wishes.

Currently the Barnes Foundation is controlled by prominent Philadelphia officials and arts organizations like the Pew that plan to move the collection out of its South Merion home to a new building run by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Don Argott’s documentary Art of the Steal shows why this would make crotchety, passionate Albert Barnes turn in his grave, chronicling the little-known rivalries, politics, and scandals that cloud the history of this monumental collection and its owner, battles that still rage today. In the process, the film raises two intriguing questions: is moving the Barnes collection legal? And more importantly, is it moral, meaning, who should own art?

The story is a difficult one to tell, spanning nearly a hundred years and at turns taking on the character of a rags-to-riches tale, a courtroom drama, and a corporate heist thriller. Art of the Steal is well researched and informative, and the filmmaker’s inclusion of seemingly every single detail related to the various lawsuits against violations of Barnes’s will makes it clear that the move is likely illegal, based as it is on deceptions and a series of shrewdly concocted loopholes. In fact, Argott crams in altogether too much information, overwhelming the viewer with so much minutiae that he sometimes obscures the inherent dramatic thrust of the story, presenting something of an obstacle to fully exploring its more philosophical half.

Argott remains so intent on mounting a case against those who wish to move the Barnes collection to a place a few miles away where it will be infinitely more accessible to the public, and on presenting a chain of increasingly nefarious corporatized and political villains, that he doesn’t allow room for both sides of his argument. The contention of these “villains” that art should be made available to the public, regardless of the owner’s original intentions, is given short shrift in favor of a succession of Barnes followers positioned as the little guys holding fast against a vast coterie of powerful institutional evildoers including Ed Rendell, the Governor of Pennsylvania, and the Pew Charitable Trust.

By so rigorously defending Barnes’s eccentricities, the film does create room to unpack the consequences of the current model of art handling, in which the donation and institutionalization of artworks is considered intrinsically “right.” If art is public it must be protected by public officials, and if protected by public officials it is subject to regulation that greatly limits how we see and experience it. Even unorthodox museums like the Guggenheims, or unconventionally curated exhibitions like the greatly anticipated Dada show that came to New York by way of Europe in the mid aughts, struggle to truly break the codified mold of white-wall viewing. We rarely question the standard method of art exhibition, one that Barnes found stifling, which is why he presented his collection in a suburban home, eccentrically grouped according to taste rather than chronology or artist.

Art of the Steal is full of such conundrums. For example: While Barnes is set up as a working-class hero, can he really continue to be such as an aged millionaire? Aren’t his temperamental, whimsical rules a hallmark of wealthy eccentrics more interested in getting their way than serving the public? With regards to Barnes’s obsession with thwarting the Philadelphia elite that spurned him, if students enrolled in the Barnes school are allowed access to the collection while the public is not, are these students not, in fact, merely another kind of elite? And if one were to side with Argott, how would these acolytes go about supporting the new Barnes correctly? Is paying to see the moved collection merely delivering money into the pockets of the bad guys, even though withholding patronage would mean not only being deprived of its beauty but also perhaps contributing to its disrepair? These questions would have represented interesting additions had they been incorporated directly rather than seeming fortuitous byproducts of the more limited focus on the narrative’s twists and turns.

Despite these elisions, Art of the Steal skillfully builds a tension via tense, dramatic scoring and a compelling mix of archival photographs and graphics. That it manages to raise questions about art and ownership and arrange them into a compelling heist structure shatters the art-world stereotype of urbane powdered socialites deciding the worth of art over tea is its greatest accomplishment. It is rare and refreshing to see people get so angry and so passionate about how and where art should be shown, a question generally considered staid, when it is even considered at all.