Reverse Shot Does It Again

By revisiting The Sopranos as one of the definitive moving image works of this century, I may be trying to say that my journey as a cinephile over these past 20 years has involved a growing acceptance that cinephilia itself has become a destabilized and unsustainable category, an antique of the 20th century.

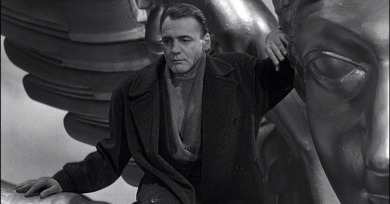

What Citizen Kane talks about is pretty much common currency everywhere now. The supremacy of the self, the squandering of talent, the exploitation of ignorance and fear, the abandonment of virtue. Welles himself lived all of this at the sharp end, while working in the film industry, from the release of Kane in 1941 until his death in 1985.

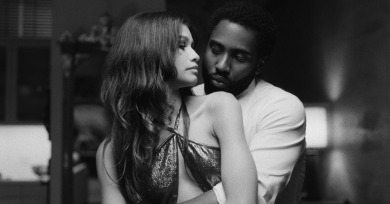

This is a film that defies tidy moral categorization, the type of film that warrants revisitation and contemplation years later—not only to assess its potential oversights but also the ways in which our grasp of representation, and its inherent complexities, must keep on evolving.

I sense my opinion about Zero Dark Thirty would have been cooler at the time had I been better versed in Bigelow’s oeuvre. But I also think my initial trepidation to express more of my political knowledge and belief systems was wrongheaded.

If the film had a low impact on me as an aesthetic experience, the act of reviewing Kaboom looms surprisingly large in my self-understanding as a “gay film critic,” a term that Robin Wood defined and dissected in his seminal 1978 Film Comment essay, “Responsibilities of a Gay Film Critic.”

This show goes beyond the initial premise of a remake or retread, to be insightful, expansive, and deeply personal. Like writing this essay is for me, the distance of time and the perspective that comes from aging allows Assayas to revisit a formative project and examine what demands to be changed.

Maybe being trans is not the key to Hedwig. Maybe transition itself is. And transition is something that I find myself thinking about frequently, not just in regards to my own experiences with hormones and gender but in the way that my own views are constantly changing.

This is a common trap for many marginalized writers seeking to prove themselves as serious and distinctive, the desire to react to media poised to be controversial or otherwise noteworthy with a mind toward showcasing personal offense rather than marshaling critical precision, and ultimately being subsumed into the raising of that media’s profile.

The anxiety of influence is real for a critic: no matter how confident we may be in our opinions and discursive and fair in our aims, we are, like those in any other field, not immune from the methodological skepticism our peers sow in us.

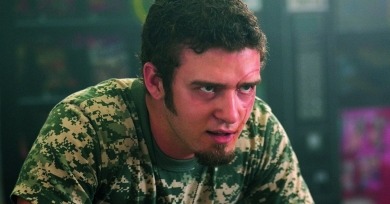

Idiocracy, kept relevant in part due to think pieces and adoptions of aspects of its worldview by both sensitive liberals and the “based” right, has never strayed far from my mind. I thought it’d be worth questioning the qualified endorsement I gave this seeming underdog and victim of 20th Century Fox’s release mismanagement.

Glazer crafts clammily immaculate surfaces that belie ripples of feeling, and so it seemed worth plunging back into Birth’s murky depths to explore the possibility of some new—or previously ignored—undertow.

Maud is not a sum total of her symptoms; neither am I. Similarly to how I experience chronic illness and a continuum of recovery, Breillat’s figure is neither reducible to her particular lapses nor to her slippery breakthroughs, those moments when she appears on the verge of self-knowing.

When you are a budding aesthete defining yourself in terms of taste, there is a certain exhilaration that comes with slagging off on something widely understood to be Good, and I was availing myself of that prerogative.

I have since spent years trying to decipher the specific pull of The American Friend. The whole experience has left me feeling much like Hopper’s Ripley, who existentially rambles into a tape recorder as he tries to understand his dislocated sense of self.

Nashville demonstrated to me not only the unorthodox modes through which character can be communicated in narrative cinema but what a film character can rightfully be, how elision and opacity can captivate and secure an investment in characters about whom we ultimately know so little.

Even if you are the protagonist of your thoughts, what is the responsible and productive way to intervene with the discourse on a particular object? Are you successfully balancing your subjectivity with research and relevant context? In the end, what kind of culture are you advocating for?

I took it all in with the wonderstruck child perspective the film cherishes, but over time some ambivalence has crept into my relationship with this beloved, hugely ambitious, and complex movie.

As my admiration for Saint Laurent has grown over the years, I have come to think that maybe some films are not made for festival viewing, or are at least best seen in relative isolation, away from the hustle and bustle of an event like Cannes or Venice.

We asked our contributors to select a film they have written about in some form in the past. It could have been a review, a term paper, a passionate email, or a Post-it note. The writer may disagree with what they wrote, or they may stand by it. Nevertheless, they are now a different person, and we wanted to know about their personal journey with this particular film.