Time Sensitive

Jordan Cronk Revisits Saint Laurent

Time as a concept essentially doesn’t exist at a film festival. Between queues, screenings, cocktails, meetings, and (maybe) meals, there aren’t many hours left in the day to write, much less write cogently. It’s an inherently compromised model, one that can cloud even the most astute critic’s judgment. In 2012, after a few years of freelancing, I abandoned the idea of becoming a staff writer at a magazine or newspaper, or even reviewing the week’s new releases for a less established outlet and started traveling to see and write about movies as a full-time festival critic.

I began covering Cannes for Reverse Shot in 2014, the same year the site became the house publication of Museum of the Moving Image. It was my third time attending the festival, which in Cannes years still makes you a neophyte, but securing a regular outlet after two years of precarious pitching ensured I’d be reporting from the Croisette for at least the foreseeable future. (Prior to this, Reverse Shot didn’t cover Cannes, so if I’m to be thanked or blamed for anything in the site’s history, it’s this.) It was a pretty plum gig, primarily because it entailed infrequent dispatches and relaxed deadlines; as anyone who’s covered a festival in the age of social media can confirm, there’s nothing worse, or more stressful, than actually covering the festival, particularly one like Cannes, which has somehow trained both the press and the public into thinking that daily reviews and instantaneous reactions are functionally helpful. In moments like these, I often think of the stories I’ve heard from Cannes veterans about the long, leisurely dinners they would have at the festival in the ’80s and ’90s, debating the day’s films over plates of pasta and glasses of rosé, weeks before they’d ever put pen to paper and record their opinion for all to read.

The 67th Cannes Film Festival was not a vintage edition. For every great film (Godard’s Goodbye to Language)—or, hell, even for every offensive one (Xavier Dolan’s Mommy)—there are any number of piddling or outright forgotten titles among the lineup (Naomi Kawase’s Still the Water, Ken Loach’s Jimmy’s Hall). What’s more revealing, looking back, are the films, typical of major festivals, filling out the middle ranks of the program—works, often by major auteurs, that for whatever reason aren’t quite as distinguished or cherished as other efforts by those same filmmakers. Chief among the qualifying titles here (see also: David Cronenberg’s Maps to the Stars) is Bertrand Bonello’s Saint Laurent, the French filmmaker’s typically stylish portrait of the eponymous fashion designer and the follow-up to his international breakthrough, House of Pleasures (2011). Regarded in many circles as an instant classic, House of Pleasures—a hallucinatory historical drama set in a palatial brothel in fin de siècle Paris—continues to cast a long shadow; many would argue that Bonello has yet to top its thrillingly anachronistic mix of period detail and postmodern formal flourishes. It was the third film I ever wrote about for Reverse Shot (for the “Life of Film” symposium, celebrating its tenth anniversary), and one I cansincerely claim made me want to start covering festivals in the first place. My initial encounter with the film came at home, on DVD, but I’ve made it a point ever since to never miss the premiere of a new Bonello film. As I write this, I’m days away from traveling to Venice to see the director’s latest, The Beast, on the Lido.

Why, then, has it taken me so long to come around on Saint Laurent? Like a lot of critics at Cannes, I was taken with the film’s style but let down by its occasionally tedious and relatively straightforward retelling of Laurent’s life. “If the film suffers from anything other than its commonplace narrative arc,” I wrote in my Reverse Shot report, “it’s in its fascination with the interstitial moments of the man’s life.” Moreover, “the film only intermittently engages with [Laurent’s] emotional, let alone carnal, interests, instead settling into a displaced perspective in its latter stretch where an elder Laurent reminisces solemnly about a life lived successfully, if, in the end, not quite satisfyingly.” If memory serves, this dispatch was written the week following the premiere and a few days after I had already filed a “first look” review of the film for a different publication immediately after the press screening. Ironically, that piece is slightly more forgiving, but by the time I sat down to take stock of the festival’s first week of unveilings for Reverse Shot, groupthink had already set in. Consensus was that the film was beautiful but kind of boring; appropriately lavish but empty—in short, a disappointment. “As macho and phallus-worshipping as any Schwarzenegger action movie,” declared The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw. “Classily assembled but narratively diffuse,” wrote Boyd Van Hoeij of The Hollywood Reporter. By the time the festival wrapped, contributors to the Screen Jury Grid had collectively bestowed a paltry 1.7-star rating on the film, third worst of the competition behind Atom Egoyan’s The Captive and Michel Hazanavicius’s The Search (speaking of memory-holed festival films). I’d like to think that with a little more distance from that first viewing I would have been a bit more measured in my assessment, but festivals have a strange way of altering perspective and uniting opinion (cf. the Sundance effect).

Revisiting Saint Laurent today, a lot of what I once considered to be flaws I now see as, if not strengths, then at least virtues of a film attempting to do something different with biopic conventions. Could it stand to be shorter? Yes, probably; at 150 minutes, it’s still Bonello’s longest film. Is it monotonous? Perhaps, but I’d argue productively so. Few films before or since have so ardently endeavored to grapple, both formally and thematically, with the duality of the creative process, its highs and lows, its pleasures and mundanities. In a lesser movie, Laurent’s days of routine design and administrative decisions would hurriedly give way to more dramatic episodes of clandestine sex and pilled-up nights of partying; here, all these things reside in the same cinematic headspace, as flip sides of the same numbed existence, to be returned to, as the character might, in an act of creative compulsion. (To that end, the relative straightforwardness I complained about is deceptive; the film treats time not as a great equalizer, but as a constantly unfolding and overlapping series of irreconcilable events.) Speaking to Bonello recently, he told me that, following House of Pleasures, his “only obsession” was for Saint Laurent to be his most personal film, reflexive in the same way that Madame Bovary was for Flaubert. “[Biopics] tend to explain why a myth is a myth. I wanted to [maintain] the mystery [of the man] and not show how Saint Laurent becomes Saint Laurent, but rather what it costs him to be Saint Laurent. There are a lot of personal details and analogies [in the film] between cinema and fashion, [particularly] the angst of creation.” As Laurent says at one point, staring at a group of models draped in his opulent designs: “I’m tired of looking at myself.”

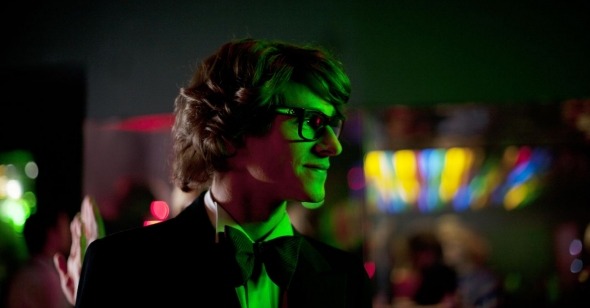

Weariness pervades the film, as does a certain melancholy due to the added knowledge that the two actors who portray Laurent at different stages in his life—Gaspard Ulliel in the artist’s younger days; Helmut Berger in his twilight years—have since died. One of the film’s first images is of Laurent lying unconscious in the dirt near a construction site after being beaten, it’s later revealed, by an anonymous man for soliciting sex. What at the time likely reminded me of the circumstances surrounding Pasolini’s death—particularly as this is just the first of many allusions in the film, both overt and perhaps unconscious, to the history of Italian cinema—now strikes an especially mournful chord that only gains in resonance as the story proceeds to its Viscontian third act and the elder Laurent begins a long, wistful look back at his younger, more carefree self. It’s moments like these that, with the benefit of hindsight, now linger in the mind more than those instances of stylistic brio that initially caught my eye, such as a neon-lit nightclub sequence in which Léa Seydoux, cigarette in hand and coifed in a chic flapper getup, dances to Patti Austin’s R&B deep cut “Didn’t Say a Word,” or an inspired split-screen montage, soundtracked by Luther Ingram’s Northern Soul nugget “If It’s All the Same to You Babe,” which juxtaposes images of late-’60s sociopolitical upheaval with a succession of fashion models descending a staircase—a scene that every contemporaneous review, including my own, was obligated to note.

As my admiration for Saint Laurent has grown over the years, I’ve come to think that maybe some films aren’t made for festival viewing, or are at least best seen in relative isolation, away from the hustle and bustle of an event like Cannes or Venice. For Bonello, whose films routinely premiere at such festivals (and who admits that critics have by and large helped his career more than hurt), it’s a matter of optics as much as accolades. “Some films really need festivals to have a light [shone] on them before they go into regular [release],” he tells me. “We needed it for Saint Laurent very much, mainly because there was another biopic on him—very different, more commercial. We needed to show the difference between the films, that mine was more ‘artistic’ and personal.” It’s hard to argue that the strategy didn’t work: Saint Laurent is Bonello’s most financially successful film, and the director credits that success with the “total freedom” he was granted on his next and most divisive feature, Nocturama (2016). Unfortunately, unlike that film, Saint Laurent has yet to accrue any kind of belated goodwill from critics, who, in this era at least, seemed to always be a step or two behind the director.

As I’ve learned, though, there’s something strangely intoxicating about Saint Laurent, something alluring, even inviting, about its soulful depiction of art and the passions that drive creativity—a feeling best illustrated by a scene in which Laurent’s lover and business manager, Pierre (Jérémie Renier), gifts him a painting of Proust’s bedroom. “I love the simplicity,” Laurent says. “It makes you want to come into the picture. To lie in bed.” At its best, Saint Laurent works similarly. Comfortable enough to sink into; rich enough to live with, it’s the rare film worth trusting with your time.