Caught in the Machine

Nicholas Russell Revisits Malcolm & Marie

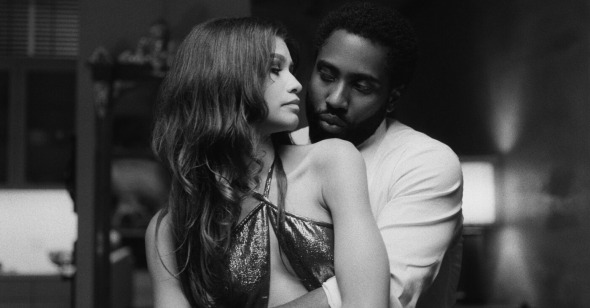

The public half-life of art in the 21st century makes an individual work difficult to gauge: the relevance of its artist, a style or color palette, a theme or mood, and whether or not the culture will eventually remember what it was momentarily so excited about. Two years ago, I wrote about Sam Levinson’s Malcolm & Marie (2021), a black-and-white domestic two-hander starring Zendaya and John David Washington. Anticipation for the film led to early, overdetermined buzz for its 35mm photography, its quick turnaround under the constraints of COVID, and unimaginative comparisons to Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The conversation that briefly flowered around the film was largely connected to its subject matter, with Washington and Zendaya’s characters, an up-and-coming black writer-director and his addict muse, respectively, railing at length against race, tokenism, film critics, gender roles, the dubious sources of creative inspiration, and love. Much or all of this invective was seen doubly: first by some as a welcome step toward maturity from a filmmaker prone to adolescent swings at underripe melodrama; second, by critics like me as a thinly veiled diatribe by Levinson himself, the speech and commentary of a privileged white director placed into the mouths of black actors.

No one seems to talk about the film anymore. On the other hand, Levinson, the son of director Barry Levinson and an eternally recurring revenant of the streaming era, has managed, in his brisk career, to dwarf the controversy and breathless press of each of his projects with his subsequent provocation. By the time of Malcolm & Marie’s release on Netflix, the first season of the HBO series Euphoria, a gritty teen drama primarily written and directed by Levinson also starring Zendaya, had been out for two years. Euphoria’s reputation as a pulpy and exploitative show luridly interested in the sex lives and reckless decisions of young adults anticipated the predetermined fuss over Levinson’s 2023 HBO miniseries The Idol, a cautionary tale about the depravities and coercions of the music industry.

In 2021, my review was far less substantive in terms of evaluating the actual film itself than I feel comfortable with now. Having rewatched Malcolm & Marie in preparation for this essay, away from the hype, relatively free of the seclusion and screen-proxied life in the immediate aftermath of lockdown, I found the film as I normally find Levinson’s work: mediocre, barely worth the handwringing it always inspires. The film has the structure and contained aesthetic of a student film, the one-location setting as a staging ground for countless arguments and misunderstandings. Zendaya plays Marie, an addict and former actress; John David Washington plays Malcolm, a filmmaker about to make his big break with a movie based on Marie’s life. Levinson shoots in a high-contrast black-and-white, which, together with his characteristic excitable handheld camerawork, long takes, and shouted dialogue, gives Malcolm & Marie the distinct feeling of effortful discernment, the filmmakers seeming to think showing a lot of work on screen equals craft. Watching the film again, I was surprised to find that Zack Snyder came to mind, a superior filmmaker often afforded the backhanded compliment that he should be a cinematographer rather than a director. I think Levinson would find such a statement flattering. He stages his scenes carefully, framing bodies in motion and landscape tableaux for maximum visual impact, a kind of “Look, Ma, no hands” approach that endeavors to contrast the verbal pyrotechnics of his script with sophisticated imagery.

When I agreed to review Malcolm & Marie for Mic, the task of cutting Levinson down wasn’t a fresh one. By then, his second film, Assassination Nation, a violent, splashy high-school satire, had been praised in the mainstream and panned by critics whose opinions I valued, with others noting the derivative similarity in content and form to Levinson’s television work. Netflix provided me with a screener of Malcolm & Marie, but I already had an axe to grind, or thought I did. In the sense that substantive negative critiques are valuable and necessary on the merit of their rigor, the voice and authority of their authors, and the opportunity they present for titillation and catharsis, doing so with Levinson’s work has always felt like low-hanging fruit. I was aware of the possibility that a negative review at a site known for snappy, high-traffic content creation would “do well.” In this case, doing well meant getting a lot of online attention, with added critical authority coming from my personal identity (there was a dearth of writers of color responding to the film’s race-oriented critiques) and my lack of fealty to Levinson’s oeuvre. My detraction became part of the hype machine. This is a common trap for many marginalized writers seeking to prove themselves as serious and distinctive, the desire to react to media poised to be controversial or otherwise noteworthy with a mind toward showcasing personal offense rather than marshaling critical precision, and ultimately being subsumed into the raising of that media’s profile.

Critiquing that which begs, even taunts, to be panned or dismissed would seem to present a double bind for the discerning critic. Malcolm & Marie is a film about scrutiny, about resentment, about the official estimations of legacy publications on supposedly challenging works of art, about the weaponization of identity in self-presentation, about discourse for discourse’s sake. Its many fights between its two characters do not flow or make narrative sense apart from the fact that this couple is, by the machinations of the script, forced to share space after a long night. There are vague echoes of A Woman Under the Influence and the work of Mike Nichols, though there is no conversation with those films, merely deliberate aesthetic association. It’s tempting then to suppose that Malcolm & Marie would have worked better on the stage, but Levinson seems to intentionally recall the long-winded monologuing of the theater while giving himself the excuse to marshal his typically showy cinematography.

He envisions each scene as an argument worth playing out in its longest possible iteration, a stand-off where one person is right, until their interlocutor cuts them down to size, before the cycle starts up again. Levinson, with the game participation of Zendaya and Washington, the latter perhaps one of the least charismatic lead actors working today, dances with meta provocation, allowing one character to spew poison against film critics and the vapid nature of Hollywood, before supplying the other character with a “Yes, but” contradiction that reframes the conversation. In essence, Levinson wants it both ways, finger wagging in every direction, sending up his audience, his worst critics, and himself, a demonstration of his self-awareness, his anger, his contrition, his detachment. This makes for an exhausting viewing experience, a film that reads as an impassioned statement shouted to no one in particular.

In the case of Malcolm & Marie, one need not cop to the film’s “insulation” from bad reviews due to its neurotic script; there’s more than enough shoddy dialogue, miscalculated acting, and wasted ambition to go around. Defiantly calling drawing attention to a creative choice as a means of showcasing self-awareness doesn’t then absolve that choice.

It may be worth pointing out that Levinson’s career is, in part, built on controversy and the fact that he works quickly, with the end product having some sort of visual distinction. Malcolm & Marie was shot in two weeks. Following director Amy Seimetz’s exit from The Idol, Levinson came on board to reshoot and finish the show in a matter of months. No one seems to talk about The Idol much anymore either. So much of the anticipation for Levinson’s work comes after the work is done and by then, he’s moved on to the next thing. In that sense, critics might have something to learn from him. The circumstances under which a project is created and released are crucial in measuring its social impact, but they can also distract from seeing the project for what it really is. It’s a matter of discernment, then, for the critic to decide what is integral and what is ancillary, a task made potentially more challenging in a landscape where hyperbole is rewarded, where studios and their marketing departments are able to find willing participants in so-called critics who trade positive reviews for early access, where aggregate scores take the place of nuanced opinion, where the notion of paying close attention to art is devalued and dismissed.

Levinson is a filmmaker suited to the streaming era for all these reasons. And yet taking his temperature is not nearly as complicated as his defenders and the PR teams of his productions would make it seem because he is not unique. As the influx of so-called content quashes the creative and labor conditions of artists, filmmakers, and crew members, the landscape of criticism must work to reflect the quality, or lack thereof, of those claiming, with superficial knowledge and condescending taste, to belong to a vaunted cinematic lineage. There is little the hype machine won’t swallow and refashion into attractive press; even negative reviews are routinely edited and added to movie posters to seem positive. But the onus of rigor and taste still rests with the discernment of the critic, who would do well to approach their work with the intention of accurately estimating what lies before them, regardless of the incentive to cop to the work’s most superficial, if vapidly pleasurable elements. Malcolm & Marie is not a product meant to age either well or badly. It is an entry in a resume. In that sense, my first review and the film itself mirror each other as shallow: invective disguised as deep-seated critique.