Routine Displeasures

Nick Pinkerton on The Hunted

My first “published” piece of film criticism, a rather harsh appraisal of William Friedkin’s Tommy Lee Jones and Benicio Del Toro vehicle The Hunted, released in March of 2003, appeared on the Reverse Shot website when I was but a stripling of 22 years. Watching Friedkin’s movie again for the first time two decades later, I found it possessed of significantly greater merit than I had given it credit for in my callow youth. Reviewing my own juvenilia afterwards, I was not particularly impressed, finding it possessed of many of the faults of immaturity and few of the virtues.

Most egregious of the faults is the author’s assumption of a position of expertise that he has not earned, as evident in the early, dismissive reference to Mr. Friedkin as a “queasy ’70s hangover.” At the moment this was written, I had seen exactly two films directed by William Friedkin: The French Connection (1971) and The Exorcist (1973). Of the two, I only had a virulent dislike of The Exorcist, which I’d first watched during a grade school sleepover in 1992 or so, when I found it rather drab and churchily solemn and not particularly scary. (I believe we watched 1986’s Fat Guy Goes Nutzoid the same night.) I revisited it as an undergraduate in the film production program at Wright State University in Fairborn, Ohio, by which point I’d read Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, which doesn’t paint a particularly flattering picture of Friedkin, and developed a more than passing acquaintance with the writing of Pauline Kael, whose tactical dismantling of The Exorcist in the pages of The New Yorker likely reinforced my resistance to the movie; I even wrote a particularly excoriating “takedown” of the film for one of my class assignments, a paper highly praised by my professor Charles Derry, whose approval meant a great deal to me at the time. It is entirely possible that this approbation instilled in me an understanding that expressing disapproval of William Friedkin was one way for a young cinephile to invest himself with an air of precocious sophistication, which of course I was eager to do, particularly at the time when I was endeavoring to impress the mysterious East Coast intellectual mandarins editing Reverse Shot, whom I had only interacted with via email at the time when I filed my review of The Hunted. (Shortly thereafter we would meet in the flesh, and I would discover that they were mere children as well.)

To the best of my knowledge, I still don’t particularly like The Exorcist, but, regardless, having seen two films does not constitute a substantive position from which to dismiss a man’s long life’s work. When you’re a budding aesthete defining yourself in terms of taste, however, there’s a certain exhilaration that comes with slagging off on something widely understood to be Good, and I was availing myself of that prerogative. A forgivable transgression, though, with hindsight, if I was going to topple an icon of New Hollywood, I could’ve had the sand to make a more provocative filmmaker to call “overrated.” Friedkin’s stock wasn’t trading too terribly high 20 years ago, and my selection of him as punching bag seems, retrospectively, a little craven, a hedged-bet move, like when people act as though it’s some kind of big heresy to knock The Doors.

I love The Doors and, as it turns out, quite a few movies directed by William Friedkin, whereas today I find the tsk-tsking tone of Easy Riders, Raging Bulls risible, and I no longer understand what I ever found infatuating about Kael, though some of her zingers and one-liners still spring to mind from time to time. Perhaps it was the brassy certitude she wrote with, something that always appeals to the insecure and inexperienced; as Hemingway has a character say of the Sage of Baltimore in The Sun Also Rises: “So many young men get their likes and dislikes from Mencken.” The appeal of Manny Farber, whose Negative Space I’d picked up at Moe’s Books in Berkeley on my first trip to California back in ’01, was something else entirely: the sailor’s knotty sentences, the frequent ambiguity or suspension of an ultimate value judgment, two qualities I found a couple of years later in the work of Henry James, who was fast on the way to becoming another obsession when I was sweating over every comma and period in my review of The Hunted. Two decades on, I still gravitate to the kind of stuff that gets you thinking rather than does the thinking for you. It’s a little out of fashion right now, but you never know what might come back around; I’ve even seen kids wearing vintage JNCOs recently.

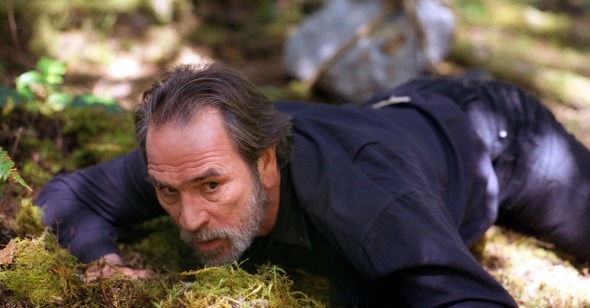

In 2003, I would’ve been midway through transitioning from my Kael Phase to my Manny Farber Phase, traces of both being evident in my (terrible) exegesis of The Hunted: Kael in the scourging tone and swipes at what I assumed to be the inscribed audience for the film (“antisocial ponytailed Tae-kwon-do enthusiasts”), Farber in a direct quotation and in some of the descriptions (Jones’s “bow-legged trundle”; Jones and Del Toro “butting paunches”—I think I was trying to approach Farber’s description of the karate bout in John Frankenheimer’s 1962 The Manchurian Candidate and failing miserably.) As it happens, The Hunted is very much a film about the anxiety of influence or, more accurately, the perils of tutelage. Jones is again a Wizard of Preternatural Efficiency (scripts centered on these kinds of hard-nosed professionals must’ve piled up in his agent’s office after The Fugitive [1993]), an expert tracker, L.T. Bonham, who, retired to the woods of Oregon after a career of training U.S. special forces operatives in how to disappear without a trace into the wild and live off the land, is called on to neutralize a former pupil, Aaron Hallam, played with spooked conviction by Del Toro, who’s gone rogue stateside and started carving up weekend deer hunters.

Has Friedkin’s film gotten better since 2003, or have American multiplex movies gotten worse? I’m guessing six of one, a half-dozen of the other, but what I can say with some certainty is that if a solid macho melodrama with a couple of meaty set-pieces like The Hunted were to come out in wide release in the Year of Our Lord 2023, I’d probably be talking it up for months like it was the second coming of Budd Boetticher to anyone willing to listen.

*****

My negative notice of The Hunted, read by as many as 30 people in the New York metropolitan area, probably didn’t damage its commercial prospects, but I’m contrite at having written it all the same. Again, I was pretty young, and youth, for good and ill, tends to hold things and people to higher standards: excellence, excelsior, or away with it! Nothing less will suffice! Among many other things, growing older is—for good and ill, again—a process of compromise, negotiation, settling: in short, of learning that a well-mounted action movie with two dead-game lead performances is, if not the absolute best that life has to offer, certainly not something to scoff at or lambaste.

Most distasteful to me today are the ad hominem digs at Friedkin, the clairvoyant flashes of authorial intention ascribing the basest of motivations to the director, another bad habit acquired from Kael. “One could say that for Kael the artist is guilty until proven guilty,” Kent Jones once wrote, and today I recoil from the interrogative traces in my review, which isn’t particularly persuasive in finding evidence in The Hunted itself that it’s an opportunistic and exploitative movie, but rather proceeds from the a priori assumption that it must be because everybody knows Friedkin is an egomaniac blowhard and a bit of an asshole—all things someone can be while still being a pretty good artist. (You could even make the argument that it helps.) Considering the opprobrium that I direct towards Friedkin, it’s kind of funny that I close the piece with words of praise for… Roman Polanski, whose The Pianist had recently been released to rapturous reviews in Fall of 2002. (For the record, I also rewatched The Pianist recently, and it is my solemn duty to report that it holds up quite nicely.)

My highest dudgeon in writing about The Hunted appears when describing the film’s cold open, which pitches Hallam, and the viewer, into a scene of wartime inferno identified as “Dakovica, Kosovo, March 12, 1999,” and its “handsomely staged mass executions” of Kosovo Albanians by soldiers from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. I wasn’t then familiar with Jacques Rivette’s excoriation of the prettified tracking shot in Gillo Pontecorvo’s Kapo in the June 1961 issue of Cahiers du cinéma, but I had seen Alain Resnais’s Nuit et brouillard (1956), and seem to be clumsily groping my way towards a position similar to Rivette’s as regards an aestheticized depiction of actual historical brutality. I also remembered Dr. Derry, shortly after the 2000 release of O Brother, Where Art Thou?, referring to the Coens’ Busby Berkeley–style staging of a Klan rally in that film as “fascist,” and generally having been imbued with a fairly strong sense of tracking shots being, yes, a question of morality—a Godardian axiom that Serge Daney, writing about Rivette writing about Kapo in 1992, would rephrase as “one should never put himself where one isn’t nor should he speak for others.”

Twenty years on, I’m contrite at being so eager to ascribe base, disingenuous motives to Friedkin, an American Jew, in his depiction of another ethnic cleansing taking place in Europe at the end of the 20th century. The Hunted opens with an extreme close-up of Del Toro’s eyes, the distinctive dark circles around them smeared with camouflage eye black, and even if Friedkin flirts with spectacle here—the shock-and-awe aerial view of the city engulfed in flame, for example—that spectacle of panic and pell-mell slaughter is one that’s understood to be aligned with the perspective of aghast witness Hallam: if not exactly what he’s seeing, then things he might have seen, or imagined seeing in his mind’s eye. (The aerial could very well be justified as Hallam’s view from an approaching helicopter drop, for instance, and though there’s one fragment of a crane shot later that might not pass the Kapo test, I’m erring on the side of generosity.) My decision to use Polanski as a stick to wallop Friedkin with is interesting here because, among other things, I was fascinated by the gradual narrowing of perspective in The Pianist as Adrien Brody’s central character is reduced to passive witness to history, spectator to the Red Army’s liberation of a razed Warsaw from the narrow view provided by a single shattered window. It’s nice to be recalled to the fact that I was thinking about these matters even as a fledgling criticaster, though in the particular instance of The Hunted I’m afraid I pooched it.

The Hunted, as it happens, is a film suffused with regret—most of the burden shouldered by Bonham who, though he never served in the forces himself, feels complicit in Hallam’s crimes, having contributed to making him an efficient government killing machine and thus responsible for cleaning up the mess left behind when that machine goes haywire on homeland soil. How Friedkin himself related to the material I can’t say, but his 2013 memoir The Friedkin Connection contains more than a few mea culpas from the man formerly known as “Hurricane Billy,” who by all accounts mellowed out significantly following his 1991 marriage to studio executive Sherry Lansing and a brush with death after a 2009 triple bypass surgery and its ensuing complications. There is a very funny filmed conversation with Friedkin and Nicolas Winding Refn from a few years back where Refn, very much the self-aggrandizing buffoon that Friedkin was once said to have been, is mercilessly mocked by elder statesman Friedkin for calling 2013’s Only God Forgives a “masterpiece.” (Refn: “It was a very inexpensive movie, so financially…” Friedkin: “WHO GIVES A SHIT?”)

*****

The Hunted was Friedkin’s final big-budget major studio film, and the last time he took a crack at making the kind of action picture that, with the release of The French Connection, had established his fame. The most distinguished of his pre-Connection features were both adaptations of theater pieces—Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party in 1968 and Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band in 1970—and, lending his career a rare symmetry, he would return to filming stage plays in his last three films, 2006’s Bug, 2011’s Killer Joe, and this year’s The Caine Mutiny Court Marshall, adapted from a 1953 two-act military trial drama by Herman Wouk, which premiered at Venice a month after its director’s death in August, and is presently available to Showtime and Paramount+ subscribers for home viewing.

In what feels like a very deliberate act by Friedkin, who must have known his days were numbered, his filmmaking life will be bookended by two courtroom dramas, his first major work having been 1962’s The People vs. Paul Crump. Made for WBKB-TV, the ABC affiliate in Friedkin’s hometown of Chicago, the 52-minute documentary is a compassionate documentary portrait of 32-year-old Death Row inmate Crump who, at the time of filming, was awaiting execution at Cook County Jail for his alleged murder of a security guard during a meatpacking plant holdup nine years earlier. A potent plea for the reconsideration of Crump’s case and sweeping indictment of capital punishment, Friedkin’s film was in no small part responsible for its subject’s sentence being commuted to life without parole—a rare feat for a nonfiction film, though in the pages of The Friedkin Connection, its director recants his former categorical opposition to the death penalty, and expresses a lingering uncertainty as to its subject’s innocence and his motives for making the film. (“I was looking for a subject to film; he was looking for a get-out-of-jail card.”)

Though I haven’t seen Friedkin’s The Caine Mutiny Court Marshall, the very fact that its director would choose such a subject for what was almost certain to be his final film, 60 years after The People vs. Paul Crump, is indicative of Friedkin’s unusual persistence of vision and his long, obsessive engagement with questions of crime and punishment, guilt and justice—an artistic conscientiousness and seriousness that I didn’t credit him with back in 2003, because I was insufficiently conscientious and serious myself.

Perhaps none of this matters, because the business of forming judgments about films and filmmakers isn’t a game with life-and-death stakes. No film critic to my knowledge has had the distinction of initiating a pogrom or saving someone from the electric chair with their work and, outside of a few exceptional cases—arguably including that of The People vs. Paul Crump—it’s awfully difficult to identify the “real-world impact” of any work of art.

Most of the text of this essay, I might mention, was written in Leskovac, Serbia, not so very far from the scene of events restaged in the opening of The Hunted, which were shot outside of Portland along the Columbia River. According to a Portland Tribune item from January 2002, the unexpected sound of controlled demolitions, special effects tests for the movie’s wartime scenes, caused a minor panic among some residents of the city’s northern precincts—this was just a few months after September 11th, mind you—but this ranks as a rather minor inconvenience compared to those faced by, for example, the Kosovo Albanians and Serbs killed, maimed, and displaced due to decisions made in distant corridors of power. “Film is a battleground,” Sam Fuller’s cocktail party aperçu in Godard’s Pierrot le fou (1965), is irresistibly quotable, but it’s worth remembering that it was delivered by a man who had seen frontline combat and been present at the liberation of the death camp at Falkenau and knew very well the difference between the real thing and a battleground for toy soldiers.

Cinema isn’t equipped to redeem our world and life as lived on it—at present, it’s unclear as to if cinema will even be able to save itself—but it does have a marvelous capacity to reflect upon both, lifelike while also presenting life in a sharper key, with the piercing focus that comes of choices regarding compression, selection, omission, and addition. An imitation of life retaining an umbilical attachment to life, then: “It was impossible to love the ‘art of the century,’” wrote Daney, “without seeing this art to be about the madness of the century and being shaped by it.”

The film criticism I return to tends to be that which scrutinizes the choices made in making a movie and considers their implications, that contemplates the relationship between a film and the world—that is, criticism of dubious market value. The one reliable, quantifiable measure by which an artwork can be valued is monetary, and criticism therefore is widely regarded as “important” only to the degree that it is able to increase or decrease a work’s worth at the box-office, to collectors, etc. I have tried to ignore the film critic’s role in the publicity machine as much as possible in my two decades of writing, or at least pretend to stand outside of it, focusing instead on more high-minded matters: trying to figure out what’s going on with a film, describe something of the experiential aspect of watching it, articulate as to if it enriches or enfeebles my sense of life, self, and of cinema, things of that nature. For the most part ignoring that promotional aspect hasn’t been difficult, because I’ve never been what you would call a high-profile film critic possessed of an institutional affiliation that would guarantee me a robust regular readership and certainly never will be, since the concept of “high-profile” film critic is close to being an oxymoron, and today the chorus of critical responses to a movie—nuanced and numbskulled alike—are ground up together into a slurry by review aggregators that determine the commercial prospects of a film more than the stamp of approval of almost any individual writer or masthead. (Is it possible for one critic to effectively lead the charge for a movie today? Would Kael’s New Yorker panegyric in support of Bonnie and Clyde move the needle, or just be one Fresh tomato in a field of Splats?)

Lately all of this has taken on much greater interest because a movie that I wrote has been making the festival rounds—the reason for my presence in Lescovac—and this has forced me to watch with anxiety over the slightest fluctuations in the Tomatometer reading that will do much to determine its fate in theatrical distribution. The central role that the Tomatometer would assume would have been difficult to imagine 20 years ago, as would the fact that a new William Friedkin film would almost exclusively be visible on streaming platforms, as would the fact that the few physical theaters it would play in would project it on a digital file, as would the ubiquity of the phrase “content”…

None of these are particularly heartening developments, and enough to make someone in my position wonder if they hadn’t wasted the last two decades of their life. Oh, well. Of the paintings Farber produced after his retirement from criticism, Jean-Pierre Gorin offers the following reading in his 1986 film Routine Pleasures: “It was the same thing that he was saying over and over again; that it—life—wasn’t too big a deal, and it shouldn’t be painted like one.” Lovingly documenting the weekly rituals of a group of San Diego–area model-train hobbyists, Gorin’s film is a paean to obsession and the satisfactions to be found from single-minded immersion in occupations that must appear as trifles to the outside world, and punctilious attention to their details. I don’t know if making movies—“The biggest electric train set any boy ever had,” per Orson Welles—“matters,” or ever did, and the use-value of writing about them is even more dubious, but as long as both continue happening, I’m convinced it’s important they be done correctly, conscientiously, with attention and care. On all counts, then, my 2003 review of William Friedkin’s The Hunted must be regarded a failure. It was my first slip-up on the job, but I doubt it will be my last.