Proposition 24: Defining a New Queer Cinema

The only true limitation we gave our writers was that their selected films hail from a year no earlier than 2000: this is an investigation into gay representation specifically in the Bush era.

A common, if under the radar, attack lobbed at Van Sant’s film is that by leaving out the facts of Harvey Milk’s alleged promiscuity, it reveals a biased agenda, to whitewash his life in the name of martyrdom.

The Wire offers a rejoinder to the valorization of the post-gay (as well as the postracial) by positing that race, gender, sexuality, and class all help to shape our experience of social life and determine how we function within social and political institutions.

Thinking about Stanley Kwan’s Lan Yu, I find it impossible to separate the film from a memory of adolescence, one that I sometimes take pleasure in glorifying as a key moment in my cinephilic puberty.

At this point in his career, Haynes has transcended the queer ghetto and connected with broad, diverse audiences who approach his cinema from a multiplicity of perspectives and for whom Haynes’s biography matters less than their own in determining how they understand and appreciate his movies.

You can only watch so many scenes of fiery young radicals holding up signs and yelling out protest songs before they all start to feel like the same damn march.

It’s no surprise that Terence Davies, ever a chronicler of fissures in the monolithic images of societal norms, would find a special kinship across time, nationality, gender, and sexual orientation with Lily Bart.

Eshaghian’s account of the current situation regarding sexual reassignment surgery in Iran is posed from a complex stance in which this procedure is not uniquely Islamic or even religious, but rather stems from a larger history of medical sciences and constructions of homosexuality and gender “confusion” as pathology.

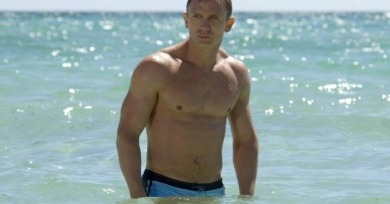

By the time Craig briefly displays his brawny physique as he emerges from the ocean, Campbell has decisively made him into an object to be looked at.

Whether unconscionable sacrilege or hyper-self-conscious camp, Travolta’s appearance is nonetheless transparent image-management of the most calculating and least entertaining variety.

His cinema is purely one of desire, surveying a new generation of young gay men whose angst comes not as much from external social pressures and the threat of societal role-playing as the pangs and thumps of the heart.

“Bromance” doesn’t suggest our culture has become more comfortable about male bonding; instead its euphemistic qualities suggest a greater sense of embarrassment and self-consciousness about it.