Never Say Never

Andrew Tracy on Casino Royale and the new James Bond

Following the success of Casino Royale, an apocryphal story sprang up that Daniel Craig had requested the inclusion of a gay love scene in the next Bond outing, complete with full frontal nudity. Although the item was quickly squelched, as much by common sense as by Craig’s adamant publicist, its overtones nonetheless remain telling. Despite the evident absurdity, there was something peculiarly appropriate in its fabricated scenario. As not once in the rumor mill’s daisy chain was it ever suggested that Craig himself was homo- or bisexual—and as his bent performances in Love Is the Devil (1998) and Infamous (2006) rarely entered the picture—the story was clearly founded primarily upon Craig’s screen persona as Bond. This particular silly rumor thus helped to crystallize the quite complex layering process that had surrounded Craig ever since he had been announced for the role, and it testified as well to the seemingly impossible feat that Craig and the behind-camera collaborators had pulled off: to re-sexualize the figure of Bond, to make Bond himself a sexual object.

This claim might seem strange, as sex (and 007’s legendary potency) has always been one of the tentpoles of the Bond franchise—but has a single one of the films after the first Connery triumvirate actually qualified as sexy? The rough, dangerous, decidedly reactionary sexuality that Connery possessed in Dr. No (1962) and From Russia with Love (1963)—nicely complemented by Ursula Andress’s blow-up doll voluptuousness and Daniela Bianchi’s good-girl-playing-bad innocence—was already being smoothed out by the time of his smirking seduction of Honor Blackman’s (coded) lesbian Pussy Galore in 1964’s Goldfinger (the one Bond girl moniker that will obviously live forever, despite the total lack of chemistry between the stars and the brevity of their onscreen time together). Before Connery (twice) exited the series, Bond’s rapacious sexuality was already part of the joke that the franchise sought to make of itself, his conquests reassuring trail markers rather than titillating encounters, all the more so once Roger Moore began his long sojourn in the role. Even when the producers tried to restore the character’s dangerous edge with the casting of Timothy Dalton, that danger was confined solely to his dispensing of violence; Dalton’s grim, angry incarnation of Bond more often viewed women as impediments to his brutal trade rather than as savory pleasures.

As many a commentator has noted, for all their de rigueur chases and explosions the Bond films are an essentially comforting phenomenon, a ritual whose pleasures are more ones of familiarity than excitement—which goes for the sex as well, the striking beauty of certain of the series’ female adornments aside. The half-hearted embrace of Pierce Brosnan was always couched in that same key of the familiar: he “looked” the part, after all, and thus assured the faithful that no surprises would be forthcoming. How different the initial reception to the announcement of Craig as Brosnan’s replacement, and how fascinating the terms in which that displeasure was expressed. The disparity between Craig’s irregular, rocky features and Brosnan’s men’s-catalogue-handsomeness invited a chorus of nasty comments, almost all of which called attention to Craig’s masculinity, or perceived lack thereof. The actor was lambasted for being too short, mocked for his (reported) inability to handle the vintage Aston-Martin’s stick shift, derided for breaking some teeth during a fight scene (a strange inversion of something that would seem rather to testify to his manly credentials).

What is curious in all this is that the Bond which Brosnan so ably and unfortunately inherited from the late Connery-Moore tradition was, as a masculine ideal, an otherworldly anachronism, a deliberate cartoon of male power and sexual potency that was received as such by the audience. Yet when Craig violated this wan image with his assertively dissimilar physicality, it was he who was criticized for a (real-life) lack of these qualities—a disparagement that, while never saying so openly, implicitly evoked tropes of male weakness and inadequacy stereotypically associated with homosexuality. Although these associations almost immediately dropped away once Casino Royale was roundly embraced both critically and commercially, the undercurrent of homosexual suggestion remained—though now framed, admiringly, in terms of male physical display rather than male weakness.

This unique evolution in the Bond franchise, the one true novelty in a series littered with false and opportunistic ones, is not only a case of audience reception but of filmmaker intentionality. After self-consciously, if effectively, signaling its revamping intentions by cleverly relocating the traditional gunsight opening logo, Casino Royale’s title sequence (created by Daniel Kleinman) violates another of the series’ ingrained rules. With only a few exceptions, the actor who plays Bond is almost never included in the title sequence, leaving “Bond” to be represented by faceless, silhouetted doubles posing with shadowy female forms—a motif which suggests that “Bond” is merely a recurring pattern, a requisite series of actions that need only be performed by the incidental actor that (temporarily) fills in the outline. Kleinman’s sequence for Casino Royale, however, first heightens this shadowplay into pure abstraction—with “Bond” and his adversaries made into blocky, two-dimensional slabs—and then violates it completely at sequence’s end by having the very real Craig emerge from his cubist double and walk into extreme close-up, chilly blue eyes staring out from set, aggressive features.

In contrast to almost all preceding films in the series, it is here the actor, rather than the character, who is given primacy, a bold foregrounding of Craig’s “un-Bondlike” bearing which heralds the “new direction” the series evidently intends to take. The revamped idea of the Bond franchise is thus intrinsically tied to Craig’s atypical physical presence in the title role—though admittedly, this novelty is predicated primarily upon scenes of violence, with Craig engaged in brutal hand-to-hand combat throughout. This led many critics, not entirely incorrectly, to label the new Bond film as a conscious evocation of the successful Bourne series, where Matt Damon’s baby-faced drone makes his way through a series of over-before-they-start battles and chases.

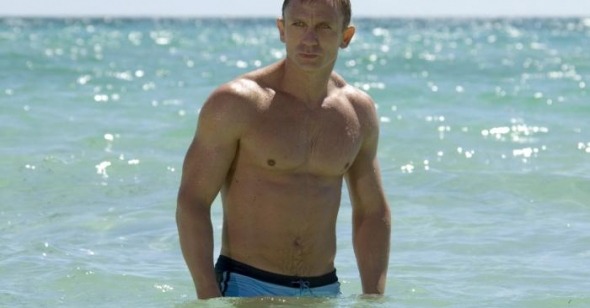

Yet unlike the sexless Damon, director Martin Campbell subtly constructs Craig as a sexual presence after the film’s first two brawls—again, a presence that is predicated on actor rather than character. Rather than the typical Bondian leers and double entendres, Campbell has Craig attract female attention irrespective of any efforts on his part: a tennis-playing duo crossing a Nassau resort’s parking lot, the concierge who unwittingly informs him of the location of his quarry. By the time Craig briefly displays his brawny physique as he emerges from the ocean, Campbell has decisively made him into an object to be looked at. And when Craig becomes far more loquacious, witty, and amusingly cocky in the film’s second half, his entire bearing—gestures, expressions, movements—becomes the film’s axiomatic principle.

It’s thus that the film’s narrative, Craig’s performance, and audience expectations become perfectly matched. In watching a Bond learning to “be” Bond, we are also watching an actor creating himself as an iconic presence, one that depends on that preexistent icon but is distinctly different from the icon’s previous incarnations. The formative narcissism of Craig’s Bond (inspecting his tuxedoed self in a bathroom mirror as a ghostly hint of the famous Bond theme plays on the soundtrack) parallels the intensity with which the audience is meant to watch him. And further, this intent, progressively eroticized focus carries over even into the “masculine” pleasures of onscreen violence, as the beatings and bruisings which Craig’s imposing bulk is repeatedly subjected to become almost fetishistic. Where Bondian violence had most often been characterized by a flippant, offhand sadism (or the painless, mechanized violence of flipping, crashing, and exploding vehicles), the insistence on pain in Casino Royale draws deliberate attention to Craig’s body, both as an index of the film’s purported “realism” and, even more, as a further insistence on the star’s tangible, fleshly being.

This union of violence and sexuality reaches its apex after Bond’s capture by Mads Mikkelsen’s archvillain Le Chiffre, as he is stripped, bound to a seatless chair, and confronted with the soul-shuddering sight of a carpet beater swung menacingly beneath his uncomfortable perch. As Craig growls, sweats, screams, laughs hysterically, and bulges his muscles throughout the testicular torture—and as the film abandons any claim to “realism” after about the third Dolby-assisted thwack to the nether regions—Casino Royale not only faithfully recreates the sadomasochistic pleasures of the original Fleming texts, but crystallizes vulnerability as the complement, rather than the antithesis, of strength. Threatened with the eradication of the very source of his manhood, Craig’s Bond instead achieves the culmination thereof. Rather than the stalwart endurance we tend to expect of our male heroes, Casino Royale depicts its hero’s extreme physique at the torturous extremity of bodily sensation; rather than drawing pleasure from Bond’s cool dispatching of sundry villains (Bond is even pointedly denied his revenge upon Le Chiffre), here it is derived from Bond’s ecstatically expressed pain.

That’s entertainment? Well, yes. From the straight male perspective (to which the present writer is unfortunately restricted), by leaving these openings into the character—by tempering invincible prowess with pseudo-realistic pain, by presenting a fantasy self in formation rather than fully achieved, by mirroring our looking at Craig/Bond by that hybrid’s own self-regard—Casino Royale recreates Bond as a genuine male identification figure rather than the parody version of same that the character had always been. And further, as it pursues this via Craig’s assertively physical, overtly sexualized presence, it makes explicit the erotic element in that process of identification. It’s for this reason that the groundless Bond-goes-gay rumor carried a certain undertone of plausibility: not because such a transformation would ever be allowed, but because this cleverly negotiated union of previously unmemorable actor and essentially formless part produces a powerful pansexual charge.

That said, it must be noted that Craig’s Bond largely abides by the dour chastity that typified Dalton, his most obvious predecessor: his seduction of a secondary villain’s mistress ends with him lying prone and uninterested on the floor while she writhes atop him, and his relationship with Eva Green’s doomed Vesper Lynd is positively chivalric (and genuinely romantic) in its final stages. Yet while Craig’s Bond can by no means be classified as a truly transgressive sexual figure, the focused attention on his physical being nonetheless reintroduces sexuality as the motor of the series. While the franchise box-office record set by Casino Royale has far more to do with the economics of blockbusterdom than any thinly conceived cultural explanations—after all, the previous champion was its immediate predecessor, the flaccid and little-loved Die Another Day (2002)—it’s undeniable that Craig and the canny Casino team quite deliberately sought a qualitatively different kind of popularity under their tried-and-true mandate. “Bond” was always an empty signifier coterminous with the actions he was required to perform; Casino Royale, alone among the Bond films, achieves the materialist’s dream by recognizing this and making it into its subject, and in doing so yields the unthinkable: a real (male) body doing the usual round of highly unlikely things, its forcefully tactile presence legitimating the familiar fantasy. And in the fearfully ascetic world of male wish fulfillment, forever trying to slough off its idolization of masculine form and style onto a rote celebration of chicks, cars, and guns, this is hardly a minor event.