Reviews

Straightforwardly titled yet bent to the max, Pornography is a shape-shifting, genre-twisting plunge into a nefarious sexual underworld that so envisions itself as a David Lynch film it might just qualify as having an identity crisis.

As with so many films that bear the “Merchant Ivory Presents” imprimatur, The City of Your Final Destination is preoccupied with legacy—inheritance, knowledge, generational conflict, the betraying or keeping of familial secrets.

A middling satire that eventually sinks into unbearable melodrama, first-time writer-director Derrick Borte’s send-up of American consumer culture is expectedly bland.

The title of the new Argentinean film The Secret in Their Eyes sounds like a crummy Anglicization of a foreign import. Alas, no, it’s a direct translation, and, ultimately, all too fitting for the moth-eaten movie at hand.

In its own wild way—and precisely because of its wildness—Ade’s film is a perfectly complete portrait of romantic entanglement. Being on the inside can be brutal, but few things are as worthy of the trouble.

Midway through Who Do You Love, Muddy Waters and his band are in a rural pool hall having a loud good time, when harmonica player Little Walter brushes against a white man in billiard shot stance. Violence erupts, epithets fly, and murder seems imminent until officers arrive (absurdly quickly) and break it up.

Breillat mounts Bluebeard efficiently and cheaply, shooting on video and casting many local, nonprofessional actors; the result recalls the intentional period artificiality of such films as Eric Rohmer’s Perceval or Robert Bresson’s Lancelot du lac.

It’s a fleet, revealing look at the studio as singular corporate entity, and thus a schizophrenic attempt to honor its toiling craftsmen while also giving due prominence to the executive infighting that made the studio in that era a target for media gossip as much as a candidate for accolades.

A lot has been written about Baumbach’s fondness for intricately arranged dysfunction, and there is something a little bit sadistic about creating two such painfully codependent pathologies and bouncing them off of each other at feature-length.

Right off the bat, The Runaways asserts itself as a period piece in more ways than one: the year, 1975, is superimposed over the first shot, which draws our attention to a clot of blood that drops like a ripe fruit from in-between a young girl’s slightly parted, mini-skirted thighs.

Marco Bellocchio sets history a-twirl in the opening minutes of his Cannes-buzzed melodrama Vincere, cutting between set-ups in Trent 1907 and Milan 1914 and back again, tripping the wire on linear narrative with rapid-fire bursts of under-contextualized, nonsynchronous events. We are somewhere in time.

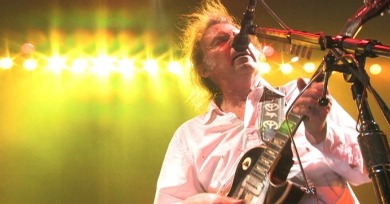

Sitting in the darkness of the theater, watching others experiencing the performance at some previous time, the concert-film viewer is always stuck on the outside, unsure whether to clap, stomp, or sing along or just watch reverently.

Besides its undeniably juicy story, perhaps what most distinguishes Prodigal Sons, and what makes its point of view so valuable, is that it’s imbued with the non-patronizing, searching voice of a transgender filmmaker.

What will future generations of film folk make of the countless American indies made in the latter half of the twenty-first century’s inaugural decade that follow inarticulate youths as they graze absent-mindedly through overgrown fields of urban anomie?