Life on the Stage

by Jeff Reichert

Me and Orson Welles

Dir. Richard Linklater, U.S., Freestyle Releasing

Like so many of Richard Linklater‚Äôs films, his latest, Me and Orson Welles, follows an ad hoc group working together towards an unlikely, and very impending, goal. In his winning School of Rock a bunch of children (and one mental child) aimed to play a great rock show. His pint-sized Bad News Bears struggled for dignity through sport and teamwork, crescendo achieved via the ‚Äúbig game.‚ÄĚ In Me and Orson Welles Linklater hops back to the 1930s to the debut of Orson Welles‚Äôs political staging of Julius Caesar, but despite this sophisticated material he still populates his movie with childish types (narcissistic theater actors, producers and designers), winding them up and letting them go. The filmmaker‚Äôs Before Sunrise/Sunset diptych may be considered his archetypal works, but in focusing on just two characters they‚Äôre atypical: few American filmmakers are as fully invested in teasing out the character of communities, and his films are always full of well-balanced personages.

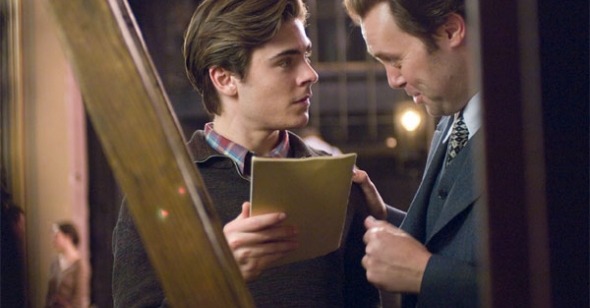

Linklater does construct heroes, leads, principals, but they‚Äôre most often subsumed into the ensemble‚ÄĒRock‚Äės Jack Black and Bears‚Äô Billy Bob Thornton both took backseats by the end of their respective starring vehicles. Me and Orson Welles has at its center Zac Efron as a theater-loving naif, but he‚Äôs neither the film‚Äôs most intriguing character, nor its most important. Efron‚Äôs Richard Samuels is a high school student with artistic ambitions who literally stumbles into a bit part in Orson Welles‚Äôs landmark Mercury Theater-opening production of Caesar. Mistaken by Welles (grandly played by relative unknown Christian McKay) for just another struggling young actor, Richard is summarily dubbed ‚ÄúJunior‚ÄĚ by his egotistical director, handed a ukulele and thrust into the madcap production mere days before it‚Äôs scheduled to open, just as the cast and crew is beginning to lose faith. This Orson is what we have come to expect of portrayals of the mad genius: brilliant, charismatic, proud, simultaneously above the fray and petty. However, unlike the Welles of our mind, most often the bloated, bearded magician of his later years, McKay‚Äôs Welles is shockingly young. Me and Orson Welles may be most valuable for reminding us of the wellspring of the legendary filmmaker‚Äôs mythology.

Me and Orson Welles is a film of the theater, and, as per the genre‚Äôs requirements, its bulk is taken up with backstage hi-jinks: personality collisions, fleeting romances, technical and creative difficulties. You‚Äôll recognize the troupe‚Äôs types and well-worn dynamics‚ÄĒfor those so inclined this kind of material is as comfortable as a slipper. If the familiar scenarios never feel stale, it‚Äôs because of Linklater‚Äôs commitment to resurrecting even the hoariest of cinematic cliches through careful study and execution. He even manages to move so quickly through a spate of Orson Welles in-jokes that references to the man‚Äôs later career never feel exhausted.

There’s nothing lazy about Me and Orson Welles, but, even so, Linklater may be somewhat too lackadaisical a cinematic sensibility for the kind of screwball comedy that the screenplay sometimes aspires towards. It’s set in 1937, the right era for whip-smart dialogues and crackling physical comedy (his production at least nails the period), but these have never been the director’s forte. He seems more comfortable in his film’s casual opening when Richard, while riffling through 45s at a music store, runs across cute Gretta (Zoe Kazan) and the two fall into a loose Linklaterian chat about the popular music of the day, their dreams, and the like. The scene feels like a potential one-off, but as with some of Linklater’s most rewarding gambits, Gretta’s seeming narrative dead-end blossoms throughout the film, providing a welcome escape from the increasingly suffocating dynamics of the production.

Though it feels somewhat in doubt over much of the film, Welles does pull off his Julius Caesar, and Linklater‚Äôs abridged version of that famed opening night is some of the most intuitive rhythmic work of his career. Linklater may be a filmmaker more noted for his meandering takes and winding dialogue, but he handles Welles‚Äôs theatrical flourishes brilliantly, popping in and out of the show at precise moments (recalling how well he adapted to rock concerts and sports games in previous films), hitting the most famous beats, and also leaving room for slight spaces that remind us that Me and Orson Welles is a film about characters, not a history piece about an important play. Add another notch to his belt; at this point in his career, Linklater has fully made the unlikely transition from classic indie auteur to ideal studio director: he skips through genres, leaving his unmistakable generous personal touch in all of them. Even if his films still register as ‚Äúindie‚ÄĚ via their price tags or distribution mechanisms, he‚Äôs definitely playing in the big leagues.

This article originally appeared on indieWIRE.com.