Figurines in a Landscape

by Eric Hynes

A Town Called Panic

Dir. Stephane Aubier and Vincent Patar, Belgium, Zeitgeist Films

The joy of watching A Town Called Panic lies in its uncanny evocation of adolescent invention. It’s an overturned toy box of a movie, complete with mismatched action figures, improvisatory effects, and stream-of-consciousness storytelling. It invites you to plop down on the shag carpet, ignore your chores, and go giddy on sugar-assisted senselessness. This film from Belgian writer-director-animators Stephane Aubier and Vincent Patar isn’t perfect, but even its missteps seem expressions of compulsive experimentation and pure play.

Stop-motion animation at its most inelegant, A Town Called Panic is about a community of stiffly posed figurines adhering to a strange but presumed logic. Cowboy, Indian, and Horse (classic mid-20th-century icons, of the sloppily-painted and sold-in-bulk variety) reside in a house on a rolling countryside. A farmer and his wife live across the street with domesticated farm animals, and a policeman is positioned nearby with a billy club perpetually cranked over his head. Cowboy and Indian room, scheme, and cause chaos together (American symbols transposed to a Belgian fantasyland, their relationship is wonderfully ahistorical). Regally comported and colored industrial brown, Horse lives downstairs and is the responsible adult of the household. Over breakfast and the morning papers, Cowboy and Indian discover that it’s Horse’s birthday. Quickly they conspire to throw him a barbeque. Yet they mistakenly order ten million bricks for the grill, an honest, if very dumb mistake soon compounded into imminent disaster for the whole town.

While Fantastic Mr. Fox has been justly celebrated for its tactility and appropriation of real-world textures, the stop-motion animation in A Town Called Panic seems even more physically present. Every little figure has volume and three-dimensionality. When they jump, leap or tumble, a tab of papier-mâché props them up. Plastic limbs aren’t fluidly moved—they’re awkwardly displaced. These are recognizable, borrowed objects from first to last, and their effect is reinforced by a general disregard for scale. Three-inch figures dance in front of a life-sized transistor radio, brush nonexistent teeth with a massive brush, spread Nutella on a giant piece of toast, and savor menacing stacks of waffles. Farmer Steven is literally half the size of his wife, Janine. Emphasizing physicality over characterization, Aubier and Patar don’t dawdle on emotional or psychological complexity (or work too hard to distinguish among falsetto voices—an acquired aesthetic via South Park and Monty Python). Instead, they put objects in perpetual motion. They’re called action figures for a reason.

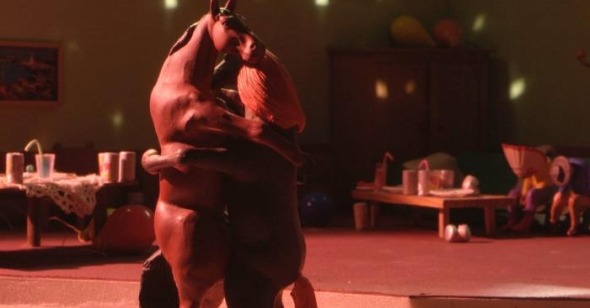

In the series of three-minute shorts that introduced Panic and garnered a cult following in Europe and online, Cowboy and Indian wreak elaborate havoc (arrows and bullets are misfired, bodies are packed in refrigerators and shoved out windows) before Horse lays down the law and cleans up the mess. End of story. Yet that simple setup and prescribed setting afford infinite anarchy. The film’s highlight is when the whole town comes over for Horse’s birthday, a portrait of small-town living in literal miniature. They stiffly dance to an amateur DJ, drunkenly teeter on prefigured stands, play interspecies poker, and flirt with each other’s wives. Dessert is proffered to the birthday boy: “Who wants some chocolate hay?”

As Cowboy, Indian, and Horse chase an aquatic beast that’s been stealing freshly bricked walls (explanation neither necessary nor helpful), they leave town and journey to the center of the earth, the arctic, then undersea. The directors manage to loop it all into their sensibility, shortening the distance between these far-flung locales (aided by giant, penguin-flipper-propelled snowballs and a deceptively deep pond), yet this globetrotting odyssey feels like baggy time-filler, and other new characters can’t compare with the core crew back in Panic (some of the film’s new quirks do work beautifully, though, especially the budding love affair between Horse and his crush-worthy, pink-maned piano teacher, Madame Longray, voiced by Jeanne Balibar). For a tiny, rather shoddily handmade town, Panic makes for a satisfyingly self-contained world.

This article originally appeared on indieWIRE.