Reviews

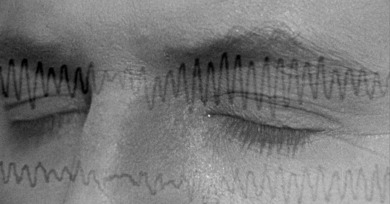

Whereas the towering novel from which it takes its name, a timely meditation on the political and cultural environment in Europe leading up to the first world war, lives largely in its characters, Chachia and Voigt’s film, instead, personifies the “magic mountain” itself to unique and ghostly effect.

Drawing inspiration from Resnais’s film and Lem’s novel (but mostly from the latter), the Polish director, film professor, and cineaste Kuba Mirkuda has created in Solaris Mon Amour a one-of-a-kind archival masterwork.

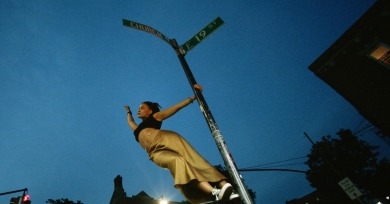

New York is always being built and rebuilt on its own ruins, and this palimpsestic vision of the city is inextricable from the consequences of gentrification—the city is always ejecting people like Dakota from its slipstream.

Around every corner, there are temptations and dangers calling him back to an old way of life. Yet in Sujo, which accompanies and expands upon Identifying Features so profoundly, hope is the sustaining force. Opening Night selection of First Look 2024 at Museum of the Moving Image.

Villeneuve smartly opts for an open-ended, portentous close, which pointedly foreswears the heroic triumphalism of your run-of-the-mill space opera.

The audience sees engine-rendered vistas shot like B-roll, in-game interviews with players staged as talking heads, the physical limitations and cinematographic mores of real-life filmmaking transposed onto the lightweight, untethered physics of a video game.

By making formless bureaucracies such as bank call centers and the United States immigration system the target of his comedy, he tries to get laughs by merely describing these systems instead of sitting with their strangeness, making the humor didactic rather than thought-provoking.

This slow-burning psychological drama is not so concerned with indicting its main character as it is in using the accumulation of detail over its 197-minute runtime to build a damning portrait of a misanthrope blind to the dark corners of his own interiority.

The specter of ephemerality hangs over the exquisitely beautiful and moving The Taste of Things, a movie that is simultaneously about food in every possible sense and also not at all, one that treats the acts of cooking and eating with reverence while recognizing in them an entry point to something more profound.

To peg the work of Bas Devos as that of a miniaturist only lays bare the limited language we use to describe a film, and our frustrating tendency to conflate budget (and runtime) with scope.

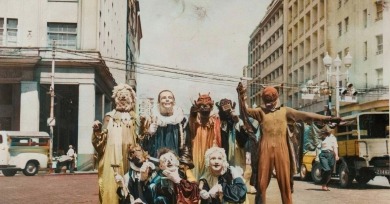

Pictures of Ghosts is as much a meditation on a home, a city, and a stretch of modern history—and how, over time, all three have evolved—as it is a memory-filled tour of a vanished world of movie theaters and other traces of film culture, tinged with a sense of loss.

On paper, these characters may sound primed for coarse caricature, these scenarios potentially played for broad laughs. But Avilés tunes her film to a minor key, elegantly and arrestingly whipping up a fine frenzy of mayhem, mundanities, merriment, and doom.

At many points, the story is deemphasized in favor of aesthetic and philosophical experimentation. In these sequences, rain, and the vivid soundscape it creates, work together with long shots, extended takes, and slow pacing to demonstrate the convergence of mortal and sacred realms.

A brutally effective journey into hell on earth, The Settlers reckons with the violent birth of modern-day Chile at the hands of Spanish colonizers all too willing to treat the people indigenous to the land as an obstacle to be cleared away like timber in the name of “progress.”