Leo Goldsmith

Being John Malkovich, it turns out, has its pros and cons. While most agree that Malkovich is a talented actor, few in Hollywood have really tested his range, preferring to use him as either terrifying or downright weird.

Carax: "Americans are hard to hate, because they're very diverse. You can't just say that they're disgusting because they live long and their eyes are shaped like the female sex. It's very different."

Tasking a handful of name auteurs (and occasionally some less familiar directors) with contributing short films to a portmanteau or omnibus film rarely results in a satisfying experience, more of a light buffet than a multicourse meal.

It’s a wonder that Aldrich acted so surprised when Sister George’s lengthy, Sapphic love scene infamously made it the first major American film to be given an X rating.

From the start, Yonkers Joe pitches the spectator directly into a world of tough-talking gamblers and sharks, where the dice are loaded, hands move quickly, and there’s always a scam in the offing.

Sympathy for the devil is a common theme in the recent crop of Nazi and Holocaust films, with Kate Winslet and Tom Cruise both imbuing varying degrees of good will in their goose-stepping characters.

This heady stew of foreign cuisine, family squabbles, and international cinema is a potent, if familiar one, and while most films play this combination for universalist, heart-warming chuckles, The Secret of the Grain is as po-faced as its wizened and weary protagonists.

It’s as if, for decades, Eastwood has been positioning himself as a brooding man’s Leonard Zelig or Forrest Gump, a witness to all of America's wrongs who’s been trying to live them down ever since.

The challenge of importing a foreign romantic comedy is thus twofold: first, it has to compete with the appeal of the American star system; and second, it has to justify its genre-mandated frivolity in a corner of the market (“world cinema”) usually reserved for much more dour films.

Cinema—its real and ersatz versions—is as much a subject of Chouga as are the tragedies and epiphanies of romantic love. Omirbaev's film is ostensibly an adaptation of Anna Karenina, an efficient reduction of 800-plus pages of text into less than 90 minutes of film.

Cinema is a time-based medium, and duration is one of its great weapons. Sitting in a darkened theater, the passive consumer of movies is beholden to the whims of the filmmaker, forced to wait for the punchline, the kiss, the bump in the night.

Grey and waterlogged, Jerzy Skolimowski's Four Nights with Anna is something like the Eastern European answer to Rear Window and Chungking Express, a deeply gothic, but no less romantic tale of voyeurism, breaking and entering, and secret love.

Shot in an unflatteringly fleshy digital video, Nights and Weekends is often uncomfortably close, an inquest into (or even postmortem of) the life of a couple.

Django, Tarantino, Miike: These names alone are enough to tell anyone whether or not Sukiyaki Western Django isfor them. If you only know the middle guy, don't bother (and for shame!); if you know and like all three, you've probably already seen and blogged about the movie anyway.

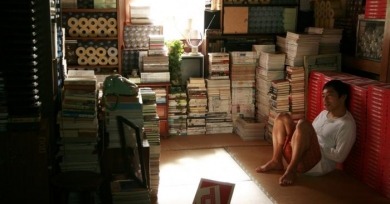

Despite the fact that children figure centrally in only a handful of Hou's films, his experience with them, as actors and as characters, played an important role in the early figuration of his style.

Lou Reed is not an artist who needs much legacy building, although throughout his career he has often required a bit of reputation rehab.

A brutally funny and relentlessly squirm-inducing film about neuroses, loneliness, and love, Expired posits the traffic cop as the nadir of self-esteem and the constant recipient of abuse and disgust.

David Lynch's films often dimly hint at the clandestine powers that control things: networks of organized crime, pornography rings, supernatural bureaucracies that hold sway from behind curtains or inside shadowy, Mabuse-like glass chambers and anterooms.

Stuff and Dough, opening this week for the first time in the U.S., charted a day-trip drug run that's no more straightforward than Lazarescu's odyssey.

If nothing else, The Life Before Her Eyes offers a unique take on post-traumatic stress disorder—or is it an acid flashback?—weaving flowers, bugs, cougars, William Blake, swimming pools, and Alice in Wonderland into Diana's wavy gravy of hallucinations.