Duel

By Leo Goldsmith

Stuff and Dough

Dir. Cristi Puiu, Romania, Mitropoulos Films

Simple tasks don’t feature in either of Cristi Puiu's feature films, both of which turn what might be quick errands into mock-epic journeys. His 2005 festival favorite and Cannes "Un Certain Regard" honoree, The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, dogged its title character's journey through a succession of Kafkaesque emergency rooms on his way to an unceremonious fate. Before that, his 2001 debut, Stuff and Dough, opening this week for the first time in the U.S., charted a day-trip drug run that's no more straightforward than Lazarescu's odyssey.

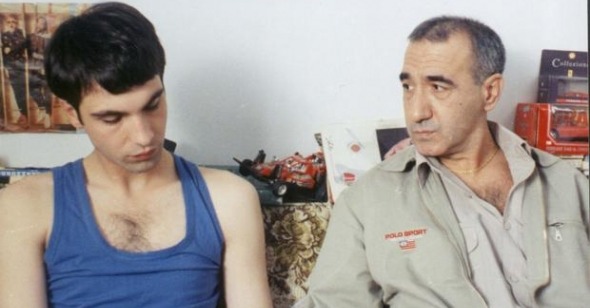

Stuff and Dough begins as Marcel Ivanov (Razvan Vasilescu), a local gangster, charges the fresh-faced Ovidiu (Alexandru Papadopol) with the apparently easy assignment of transporting "medical supplies" from the city of Constanta to Bucharest, a four-hour trip. As Marcel enumerates the job's few particulars, we briefly glimpse a poster for Get Shorty (alongside similar ones for Iron Maiden and Pink Floyd's The Wall) aligning Ovidiu's bedroom wall. This might well be all the young transporter-to-be knows of gangsters and shifty characters, and Marcel might as well be a Romanian Dennis Farina, paternally patting Ovidiu's head with hairy hands and casually asking him—by way of summing up the young man's character—what time of day he normally takes a shit. Marcel is a morning guy; Ovidiu, in a sure sign that he's liable to pull a fast one, defecates in the evening.

Ovidiu might not be quite smart enough to pull a fast one, but as is common in movies like this, he doesn't follow his employer's instructions to the letter either. Whereas Marcel has told him to go alone and tell no one, Ovidiu immediately rings up his friend Vali (Dragos Bucur) to come along. In turn, though Vali is told to come alone, he nonetheless brings along his new girlfriend, Bety (Ioana Flora). This is a sort of parodic variation on the classic film noir set-up wherein a perfect plan goes awry because of a few small deviations—except in this case the plan is merely a simple set of instructions that Ovidiu and company are too clueless to execute.

But these aren’t your usual gangster movie stooges, anyway: Ovidiu and Vali are mere boys, more interested in quibbling about cars or ogling girls than they are high crime. They are young and excitable, but also ingenuous: the money that Ovidiu is to earn from the job will help him buy his own stall to sell drinks and groceries like his parents, a goal that seems his highest worldly aspiration. To placate his nagging mother, he agrees to make some time during his trip to Bucharest to pick up some beer, soda, and oil at a wholesale market, another diversion from his appointed task that threatens to derail the entire operation.

While the extent of Ovidiu’s innocence occasionally strains credibility, Puiu has christened him (as he did the pitiable Dante Remus Lazarescu) with a name that indirectly suggests a somewhat loftier slant on the film's events. Ovid, who is apparently buried near Constanta, is our hero's namesake, and the metamorphosis that Ovidiu undergoes, while not supernatural, nonetheless nudges him from innocence to experience somewhere along the highways of Romania. As played guilelessly by Papadopol, Ovidiu is wholly naïve to the dangers he faces until he finds that he and his friends are being tailed along their route by a couple of armed thugs in a red SUV. As Lazarescu sticks close to its titular character's gurney, Stuff and Dough remains largely in the back seat of Ovidiu's van, following the journey's pitfalls and pit stops in neorealist long takes and jump cuts.

Once in the van, Stuff and Dough becomes Duel on downers—if this were an American film, it would most likely play out as a stoner-comedy variation on The Wages of Fear. But what keeps it refreshing and even, in its own way, gripping is that it resists glib characterizations, just as it avoids the conventional genre satisfactions of high-speed car-chases and deals gone wrong. As in Lazarescu, Puiu’s tone isn't quite blackly comic—it doesn't simply cut its characters adrift and watch from a condescending remove as they scramble towards their fate. Rather, it retains empathy for—even a proximity to—these characters who, despite their green-ness and lack of ambition, are trying earnestly to make their way. Ultimately, like Lazarescu, Ovidiu becomes a mere cog in a social and economic system that would chew him up without a moment's consideration, and it's Puiu's goal to elevate this and other such stories above their banality and into the realm of myth.