Nick Pinkerton

The evident work that went into rendering the details of every banal gesture complements the material, for crabbed Michael is a man for whom every piece of common courtesy is an agonizing chore.

As with Django Unchained, what we now tend to refer to as “America’s troubled racial history” is central to The Hateful Eight, though the racial hang-ups attributed to America are naturally filtered through Tarantino’s own, as surely as the streak of podophilia running through his films is no accident.

After breezing along for more than half of its running time, the film takes a turn for the tone-deaf and wrong-footed, never worse than when expressing fraudulent concern for “common people.”

To call this misty, low-risk collection of calculated revelations a high-toned The Bucket List would be a disservice to Rob Reiner.

It isn’t the conceptual spin that ultimately undoes Kurzel’s Macbeth, but his ponderous approach, hefting each scene on top of the last as though moviemaking was an act of grunting, straining brute force, stacking up a big, bleak cairn.

Instead of trying to reproduce Milgram’s work and life within a traditional dramatic framework, Almereyda draws out a parallel between the manipulation which occurred in the Milgram experiments, and that which occurs in film drama.

Following high-wire walker Petit from France to New York City in his monomaniacal pursuit of his mad fantasy, the movie shares its subject’s single-minded dedication to the cause, and this lends it a propulsive momentum.

It is a film of indelible portraiture; the plot, as it is, exists largely to transfer our protagonists (and the camera) between congregations of winos, from gin mills to games of dominos around a flophouse common room’s pot-bellied stove.

The wide-gauge format reached its greatest popularity in the 1950s amid a boom of new innovations intended to reverse the fortunes of foundering Hollywood studios; for a time, they even appeared to have done the trick. But every great reign is followed by an epoch of decadence . . .

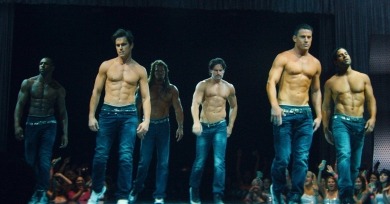

Magic Mike XXL is able to express something about catering to fantasy life with such clarity because it deals with the business of female fantasy—or, rather, the prepackaged version of female fantasy filtered through available cultural signs and symbols and enacted in the arena of the strip club.

For many of us, at some point in our upbringing, the movies variously played the part of babysitter, behavioral role model, playground inspiration, and substitute parent. For the six Angulo Brothers of the Lower East Side, stars of The Wolfpack, you might say that the movies were very nearly everything.

A compact 94 minutes, Heaven Knows What is a movie with feverish drive, dragged this way and that by Harley’s appetites and Ilya’s whim to carrot-on-a-stick her around with the promise of reciprocal affection. Throughout, the perspective commutes regularly between swooning intimacy and bystander detachment.

Tomorrowland is a folly and a failure, though there is something touching in its failure, tied as it is to the vision and personality of Walt Disney himself. No less than the Brook Farm and Oneida settlers, Disney was part of an American tradition of Utopian ambition.

There are easy jokes about academia ripe for the taking here, though L for Leisure mostly skips them; in fact, it often gives the sense of being too “mellow,” to borrow a word used prominently in the film, to bother with punchlines at all.

The film is a comedy of camera mismanagement in which every 1.85:1 aspect ratio framing is ever so precisely wrong—or fails, rather, to be in the “right” place. Watching it, one is acutely aware of the thin line that separates classical screen grammar from gobbledygook . . .

“I think that creation and life are inextricable, and beyond this there is nothing else. If a filmmaker isn’t a marketer, then essentially his work is the reflection of life through his own unique spiritual and psychological perspective.”

The subject matter here may sound grim, but beneath this is a sentimentality that will be familiar to viewers of such films as Benji the Hunted and Homeward Bound: The Incredible Journey, Disney productions that specialize in assigning recognizable, sympathetic human motivations to animal protagonists.

Nicloux’s film is quite the best cinematic supplement to Michel Houellebecq’s work that exists.

"I had the impression as a child, from the age of five on, that man exists through language. Here, I had the impression that the world didn’t exist through language. What was around me seemed unreal, so I sought a reality in literature, later in other arts and music, cinema also, very much."

The film proceeds as a series of vignettes, mostly interiors, almost entirely shot with a stationary camera, a self-imposed rule which Hausner will here and there violate for a slight pan or a slow zoom, her austerity coming up just shy of that found in the period pieces of Rossellini or Straub-Huillet.