Nick Pinkerton

Potrykus has a way of distilling the familiar adolescent spirit of contempt for this environment—which is, after all, contemptible—and shows indications of being the rare filmmaker capable of stirring up ideas about class in America without resorting to the usual drab, po-faced miserablism.

Poverty, of the sort that scarred young Christian both physically and mentally, appears in Fifty Shades of Grey only as an abstraction, a source of blockages to be “overcome” on the way to normative reprogramming.

Rather than Powell-Pressburger’s distinctly Anglo-Saxon mysticism or Huston’s folk-grotesquerie, Macdonald’s style hews close to the currently accepted tenets of realism, a matter of busily plucking out isolated details, which achieves a strangely disconnected and flattening effect.

I’m placing the scare-quotes on “film” culture because after a good 115-year run, shot-and-displayed-on-film moving image art is no longer standard, or even particularly common, in any idiom. This is not, in and of itself, a tragedy.

Mr. Turner, an unconventional biopic of England’s most famous landscape painter from director Mike Leigh, does not endeavor to show the world as seen by Turner, but to show Turner in the world. It’s a movie about a man who isn’t particularly pretty—neither physically nor morally—but who produces beautiful things.

In My Neighbor Totoro’s almost complete abjuration of kiddie movie standbys we have a small tale, simply told, but resplendent with details in its “pictures of ordinary days.” There is always a sense of ongoing life at the periphery of the events depicted.

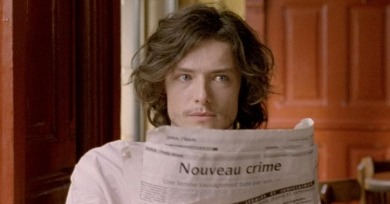

A thought that occurred to me while watching Albert Serra’s Story of My Death: the lot of filmmakers traveling the prestige Euro festival circuit is not incomparable to that of the itinerant gentleman of prerevolutionary Europe.

This may be difficult to believe today, but there was for a moment a sense that Carrey was an actually dangerous, destabilizing force.

The first thing that you should know before watching Tommy Lee Jones’s The Homesman is that it operates under the fundamental assumption that everyone who took part in the settling of the American West was, by almost any contemporary standard, insane.

An inventory of just about everything that the cinema could do in the year 1931, quite a lot of which still outlines its capabilities today.

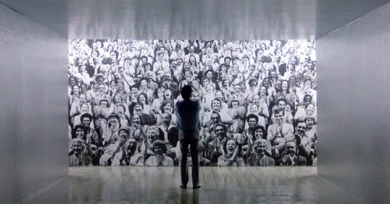

The phrase ahead of its time is a problematic one, as it is premised on the idea that any given time has a single defining attribute. Applied to The King of Comedy it’s even trickier—have we really caught up with Scorsese and De Niro’s film?

Pedro Costa’s Horse Money, Manoel de Oliveira’s The Old Man of Belem, Gabriel Abrantes's Taprobana, Eugène Green's La Sapienza, Alexandre Larose’s brouillard - passage #14, Eric Baudelaire's Letters to Max

Stray Dogs is a disturbing movie, not only because Tsai denies us any period of relaxing cruise control, but because he piles one long take after another atop the viewer, as to impress a sense of the weight of time.

Anderson adores overtures overburdened with backstory, and The Grand Budapest Hotel has a particularly ornate framing device: the movie proper is nestled within an elaborately impractical nesting doll–type structure. This is only suiting for a film besotted with the lovely and the useless.

Seidl sees the twenty-first century using the compositional values of the fifteenth, as evidenced in his flat, compressed tableaux, in which cell-like interiors are captured at a stationary medium long-shot, figures held flush in their center.

The first half of The Grandmaster is set in a period that’s new to Wong’s cinema: China before the revolution. (I am excepting the setting of Ashes, more mythic than historical.) This is not the decadent, Westernized jazz age Republic, but a world steeped in centuries-old continuities, a 1936 where the imperial past is still not really past.

Certainly The Canyons didn’t have a private life at any stage of its production, nor have two of its stars had one, in any traditional sense of the word, at any point in their adult lives.

Studio head William Fox bet the farm on The Big Trail. It was one of only a handful of features shot on 70mm Grandeur film, a.k.a. Fox Grandeur, an early widescreen process which had only been in use for about a year.

In Forty Guns, Stanwyck is on the way out of movie acting—the television box was more forgiving—fifty years old and not looking a day younger, a little stoat-like with her curled lips, the hardness of her wave just offset by the purr in her throat.

In the City of Sylvia, Jose Luis Guerin’s odyssey of perception, is so dedicated to getting inside the act of cosmopolitan female-watching, it might as well be called City of Women.