What Is 70mm?

A History of Wide-Gauge Cinema

by Nick Pinkerton

It is the format of imperial pomp and imperial folly. It is a tool for showmen that has occasionally found its way into the hands of artists, and sometimes the showman and the artist have been one and the same person. The wide-gauge format 70mm reached its greatest popularity in the 1950s amid a boom of new innovations (Cinemascope, Cinerama, 3D) intended to reverse the fortunes of foundering Hollywood studios; for a time, they even appeared to have done the trick. But every great reign is followed by an epoch of decadence, and the heyday of 70mm encompassed smashes and busts: Oklahoma! (1955) but also Dr. Doolittle (1967); Ben-Hur (1959) but also Cleopatra (1963). One of the greatest films shot in 70mm appeared at the cusp of its popular decline, Anthony Mann’s significantly titled The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). Now Quentin Tarantino, the most high-profile (or at least the most grating) public advocate for preserving analog celluloid as an exhibition format, has shot his The Hateful Eight on the all-but-extinct Ultra Panavision 70, making a crackerjack piece of advance publicity of this fact. The film will open on Christmas in—one expects—nearly every 70mm-equipped theater in the country. As to if this signifies a rise or fall of the format, and in the industry as a whole, remains to be seen.

1. Early Experiments

The appeal of the wide-film image is a combination of consuming clarity and enveloping breadth. Audiences have always been in thrall to the impression made by sheer size, and all the more so when they can lose themselves in a delicate fretwork of detail within that largeness. Herein lay the draw of the original “blockbusters,” paintings on the grand scale teeming with brushstrokes, like the Belshazzar’s Feast (1821) of John Martin, that Cecil B. DeMille of the 19th century; the heroic nationalist mythologies of Jacques-Louis David and John Trumbull; or Frederic Edwin Church’s jungle vista The Heart of the Andes (1859). These are paintings whose subject matters—immersive exotic environments separated from the culture that produced them by vast historical or geographic distance, military fanfare, and the movements of massed men—would often be echoed by those of wide-gauge cinema.

We can’t say how, exactly, the original innovators of wide-gauge celluloid would’ve explained their compulsion toward bigness, but while wide-film formats reached their pinnacle of public visibility from about 1955 to 1965, the history of wide-film goes back very nearly to the birth of cinema. The most touted early innovators of the celluloid motion picture camera on either side of the Atlantic, Auguste and Louis Lumière in France and Thomas Alva Edison and W. K. L. Dickson in the United States, both used a practical, puny 35mm film strip for their early cameras and projectors, though at the time it was by no means the only possible option, and other contemporaries had ideas of their own. Stateside, Edison tried unsuccessfully to exclusively patent his four-perforation 35mm filmstrip. This attempt was struck down by a 1902 court ruling, but until then cautious competitors were forced to experiment with their own formats of varying sizes. Birt Acres, who invented the first 35mm moving picture camera in England and who some consider to have been out ahead of the Lumières, shot a 70mm film of the Henley Regatta in July of 1896. Dickson, after leaving Edison’s employ, experimented with a 68mm filmstrip at the American Mutoscope & Biograph Company, feeding it through the projector by means of unreliable rubber rollers. France’s Demeny-Gaumont produced a 60mm film, while Prestwich in the U.K. made the 63mm negative on which the first wide-gauge hit of early cinema was shot, depicting the entire fourteen-round fight between boxers James J. Corbett and Bob Fitzsimmons in Carson City, Nevada, on St. Patrick’s Day in 1897. (Its unusual 1.65:1 widescreen frame, which captured a broader swath of the ring, was dubbed “Veriscope,” an early episode in the long history of hanging silly names onto wide-film processes.) Even the Lumières got into the act, exhibiting a 75mm “widefilm” at Paris’s Universal Exposition of 1900, where the other attractions included Cinéorama, an immersive early virtual reality ride devised by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson which used ten synchronized 70mm projectors to reproduce the experience of hovering over the Jardin des Tuileries in a hot air balloon. (The Cinéorama was shut down after only four days for safety reasons, but its spirit would live on in such novelty formats as Fred Waller’s eleven-projector Vitarama at the 1939 World’s Fair.)

After these early years of idiosyncratic film formats run amok, the Edison-established Motion Picture Patents Company fixed 35mm as the national standard in 1909, and the Congrès International des éditeurs de films in Paris followed suit shortly thereafter. While this thinned the herd of nonconforming wide-film formats, it didn’t end experimentation on wide-gauge film outright. Filoteo Alberini, an Italian exhibitor and cinematographer who had been dabbling in wide-film since the turn of the last century, introduced his 70mm Panoramico Alberini in 1914. John P. Berggren and George Spoor, a cofounder of Chicago-based Essanay Studios, tinkered incessantly with a 63.5mm process called “Natural Vision,” which they used to shoot views from a roller coaster and the Niagara Falls with the intention of inducing potential investors, screening the results in 1926. (A January 1930 article in American Cinematographer on “The Early History of Wide Films” claims that Berggren and Spoor “have worked for more than ten years” on Natural Vision.)

The Natural Vision process would be little employed in feature filmmaking, being used on The American (1927), a now-lost western made under the auspices of “Natural Vision Pictures,” and Danger Lights, a railroad yard drama released by RKO that had its wide-gauge engagement at Chicago’s State Lake Theatre in November 1930. By the time that RKO had begun monkeying around with Natural Vision, they were playing catch-up with the other studios, who’d been testing out their own wide-gauge, widescreen films. Fox Film Corporation introduced their 70mm Grandeur process in 1929, and released a handful of films in it, including Frank Borzage’s Song o’ My Heart and Raoul Walsh’s The Big Trail, both in 1930. They would appear at roughly the same time that Warner Brothers, not to be outdone, was unveiling John Francis Dillon’s Kismet (1930), playing in ten cities across America in 65mm, 2.05:1 Vitascope, and that MGM trotted out its 70mm, 2.13:1 Realife, essentially employing the licensed Grandeur camera and lenses, showcased on King Vidor’s Billy the Kid (1930).

In addition to widescreen processes using wide-gauge film, there were several that attempted to create a larger image without abandoning the 35mm format. Perhaps the most famous of these is Polyvision, the simultaneous projection of three synchronized 1.33:1 images that allowed for the triptych scenes in Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927). Along similar lines, in 1921 George W. Bingham and John D. Elms invented a process called Widescope, in which a double-lensed camera recorded images onto two 35mm strips, which combined for an effective 2.66:1 aspect ratio when projected side-by-side. A process called Magnascope was used in exhibiting the maritime battle scenes of Paramount’s 1926 Old Ironsides. At the film’s debut at the since-demolished Rivoli on Broadway and 49th, the image suddenly expanded at a crucial moment in the action, nearly tripling in size from 12 x 18 to 30 x 40 feet as Dr. Hugo Riesenfeld’s orchestra performed “Ship of State.” (Magnascope was also employed in select sequences in other Paramount films, including Chang and Wings.) The effect was produced using a lens on the projector that literally magnified the 35mm frame, enlarging image and grain alike, and resulting in a coarse, low-resolution picture, leading Paramount to further experiments with 56mm Magnifilm, their answer to Grandeur, Vitascope, and Realife. Combined, all of these bits of trial and error and stymied innovation evoke an image not unlike archival footage of failed flying machines, always used to redoubtable comic effect.

These simultaneously occurring developments would appear to presage the wide-gauge, widescreen revolution, but that industry upheaval would have to wait for more than another two decades. This was a matter of economics, pure and simple—there was a Depression at the time, for starters, and moreover exhibitors had just laid out the cash to retrofit their booths and theaters to accommodate new sound-on-film technology, and were in no position to put themselves in hock by paying for another makeover. Until the 1950s, most high-profile developments in film format would involve new narrow-gauge stocks for home usage. Then, at midcentury, faced with new competition and dwindling audiences, the studios struck on supersizing the screen as one way to reestablish moviegoing as an event. As the question of how to get a bigger image without concurrently sacrificing image quality was raised, the old wide-format processes, long malingering in neglect, were waiting to be picked up again.

2. The Big Fifties

The key figure in the return of wide-format cinema was a flamboyant Minneapolis-born theater impresario named Mike Todd, who had entered the motion picture business in 1950, helping to bring a process called Cinerama before the public eye. Fred Waller, earlier of Vitarama fame, had invented Cinerama some years previous, but until the intervention of backers Todd, Lowell Thomas, and Merian C. Cooper, codirector of the Magnascope classic Chang, he had been unable to produce a practical demonstration of it, in part because of the exigencies required for its exhibition—projection of the Cinerama image involved three interlocked projectors running simultaneously, à la Polyvision, their beams combining to create a single image on a special curved screen.

This Is Cinerama, the long-deferred coming-out party for Waller’s process whose scenes included a new variation on the old Natural Vision roller coaster ride, premiered at the Broadway Theatre in New York City on September 30, 1952, but by that time Todd had already left the company, seeking to invest in a widescreen technique that would eliminate the exorbitant demands that Cinerama placed on an exhibitor. The resulting product was Todd-AO, a single-projector widescreen format using a 65mm camera negative and 70mm release print. The “AO” stood for the American Optical Company in Buffalo, New York, where the principal architect of Todd-AO, Dr. Brian O’Brien, the director of the Institute of Optics at the University of Rochester, midwifed it into existence. Todd’s other partners included George Skouras, President of United Artists Theatres, and Joseph Schenck, a veteran studio executive who’d produced Roland West’s 1930 The Bat Whispers, the only film shot in 65mm Magnifilm—no apparent relation to the 56mm Paramount process—with whom Todd formed the Magna Theatre Corporation.

Besides lending the new technology his namesake and oversight, Todd concentrated his efforts on its behalf to his area of expertise: ballyhoo. For the first Todd-AO feature, he set out to sweet-talk composer-librettist team Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, then nothing less than an American institution, into selling him the rights to their 1943 stage hit Oklahoma!, which offered a hummable songbook and, in its “wind comes sweepin’ down the plains” locations, plenty of picturesque opportunities to show off the process. Rodgers and Hammerstein were sufficiently impressed by the Todd-AO demonstration film that they were shown, depicting the canals of Venice, to give Todd and his partners the go-ahead, and Oklahoma!, directed by Fred Zinnemann, premiered on October 11, 1955, at the Hollywood Egyptian in Los Angeles, equipped for the occasion with a mammoth new curved screen intended to emphasize the enveloping embrace of the extreme wide angle photography. Oklahoma! handily earned back its original budget, and the next Todd-AO film, Michael Anderson’s star-strewn Around the World in 80 Days (1956), was a gargantuan hit. A contemporary parody (Around the Days in 80 Worlds) in Harvey Kurtzman’s short-lived humor magazine Humbug refers to “Mike Toddy” and his “Toddy A-OO-AH-EE wide screen, bringing movie talkies a step closer to feelies,” while its dialogue razzes the perceived excessive breath of the 2.20:1 Todd-AO frame:

“I’m sorry, Mr. Fogg! We’ve run out of fuel. We can’t find another scrap of wood in the box! We’ll never make it back to England in time!”

“Have you searched both ends of the Toddy-A-AH-E-O wide screen? Surely there is wood somewhere in those vast expanses.”

The successes of Oklahoma!, Around the World in 80 Days, and Todd-AO triggered the second coming, after the late 1920s, of the wide-gauge rush. After Cinerama, the appearance of CinemaScope had expanded the accessibility of widescreen movies—though the latter, by taking over more screen real-estate without a corresponding increase in the size of the film area that was being enlarged through projection, effectively downgraded the resolution of the image being shown, a variation on the old Magnascope conundrum. Fox, who’d been unusually committed to Grandeur, had released the first shot-in-CinemaScope feature, Henry Koster’s The Robe, in fall of 1953. They were also the first on the wide-gauge bandwagon, taking a page from Todd’s playbook and introducing their “Cinemascope 55” with two tried-and-true Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals, Carousel and The King and I (both 1956). Cinemascope 55, as the name suggests, used 55mm film, shot on a modified Grandeur camera, though both Carousel and The King and I were exhibited in 35mm and 70mm. Ultimately, equipping theaters for 55mm projection was deemed impracticable, and Fox entered into an exclusive arrangement with Todd-AO beginning with their next Rodgers and Hammerstein adaptation, South Pacific (1958), which also abandoned some of the more idiosyncratic elements of Todd-AO: the thirty frames-per-second frame rate and the curved screen. After Todd’s death in plane crash in spring of 1958, Fox assumed control of the Todd-AO process, and over the next decade the Todd-AO label would grace films including Porgy and Bess (1959), The Alamo (1960), Cleopatra (1963), The Sound of Music (1965), Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965), The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), Krakatoa, East of Java (1969), and Airport (1970), with increasingly less prominence as the brand’s early luster began to fade.

3. Further Expansions

Todd’s death came just as the wide-gauge boom that he’d envisioned was entering its full swing. His soon-to-be-widow, Elizabeth Taylor, would, some time before Cleopatra, star in Raintree County (1957), the first film shot in MGM’s 65mm Camera 65 process, distinguished by its band-thin 2.76:1 aspect ratio. After Ben-Hur (1959), the Camera 65 name was retired, and the format was renamed Ultra Panavision, used on films including Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), The Battle of the Bulge (1965), and Khartoum (1965). (The Hateful Eight will be the first feature outing for Ultra Panavision in nearly forty years.)

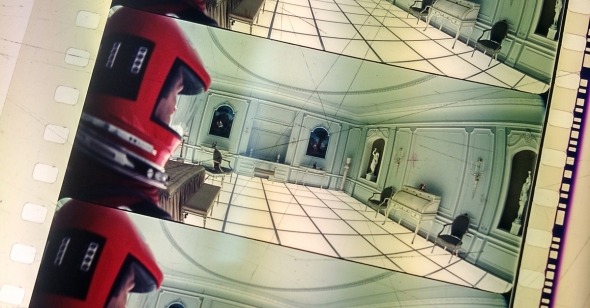

Camera 65/Ultra Panavision was developed with the assistance of Panavision, a Los Angeles company who’d made a fortune by manufacturing anamorphic lenses in the early days of widescreen, and who would later debut a wide-gauge format of their own, the somewhat confusingly named Super Panavision 70. Walt Disney Pictures’ The Big Fisherman (1959), directed by a past-prime Borzage, was the first Super Panavision 70 production, followed in short order by Exodus (1960), West Side Story (1961), My Fair Lady (1964), Cheyenne Autumn (1964), and perhaps the two most famous wide-gauge productions of all time, David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Super Panavision would be the preferred format of the few 1980s wide-gauge revivalists, including Tron (1982) and Brainstorm (1983), though its credits for the latter half of the 60s are hit-and-miss, including Lord Jim (1965), Grand Prix (1965), Ice Station Zebra (1968), Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), Song of Norway (1970), and Lean’s Ryan’s Daughter (1970).

Lean, whose Doctor Zhivago (1965) was also released in a personally overseen 70mm blow-up, though MGM only budgeted him to shoot in 35mm, was one of a handful of directors to wholeheartedly embrace wide-gauge; Otto Preminger, Anthony Mann, and Robert Wise all got more than one wide-film movie under their belts. John Huston, for his part, never met a novelty presentation he didn’t like; he’d had his 1956 Moby-Dick treated to an early version of the desaturating bleach bypass process, had Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967) tinted a jaundiced yellow to mute the colors of DP Aldo Tonti’s cinematography, and with The Bible… In the Beginning (66), debuted the 70mm Dimension 150 system. D-150 for short, Dimension 150 was the invention of Dr. Richard Vetter and Carl W. Williams, two members of the faculty in the Audio-Visual Communications department at the University of California, who created it by adapting the basic principle of a driving simulator that they’d designed. Like Cinerama or the early Todd-AO, D-150 was intended to be shown on a curved screen—a 120-degree arc, to be specific—and making this costly modification a prerequisite ultimately doomed it; Franklin J. Schnaffer’s Patton (70) was the next and last film made using the format.

Along with the wide-gauge processes came various pseudo-wide-film techniques. The most widely used of these was Technirama, a process developed by Technicolor as an anamorphic alternative to CinemaScope, introduced in a 1956 promotional film called The Curtain Rises on Technirama. Technirama in fact used 35mm film, though run through the camera horizontally; the larger, horizontal film area was meant to produce a sharper image than CinemaScope, and often release prints were optically printed in 70mm from the 35mm negative and billed as Super Technirama 70. Marlene Dietrich vehicle The Monte Carlo Story (1957) was the first feature shot and released in Super Technirama 70, and over the following decade the format would be frequently utilized in shooting sword-and-sandals films and historical epics, acting as something like the house format for producer Samuel Bronston, who briefly made a cottage industry of producing that sort of material in his studios outside of Madrid. (King of Kings [1961], El Cid [1961], 55 Days at Peking [1963], Circus World [1964]), while flamboyant Neapolitan Dino de Laurentiis, who would use D-150 for The Bible and Ultra Panavision 70 for Battle of the Bulge, dabbled in Super Technirama with Barabbas (1962), directed by early CinemaScope master Richard Fleischer.

Some Super Technirama 70 credits with auteur interest include Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960), Nicholas Ray’s The Savage Innocents (1961), Vittorio Cottafavi’s Hercules and the Captive Women (1963), and Cy Endfield’s Zulu (1964). Just as often, however, Super Technirama 70 would be the vehicle for little-remembered international coproduction cash-ins like Imperial Venus (1962), La Fayette (1962), and The Golden Head (1965). Taken altogether, the history of Super Technirama 70—and the Golden Age of wide-film formats—doubles as a snapshot of movies in the first age of runaway production, when “Hollywood” talent and money decamped from Southern California to Europe, taking advantage of exchange rates and tax shelters. Meanwhile European-based industries, while somewhat slower to adapt, developed their own widescreen techniques and wide-gauge formats. Jacques Tati filmed his Playtime (1967) with 65mm Mitchell cameras and premiered it in 70mm at the Paris Empire, where it showed in an unorthodox, rather “tall” 1.77:1 aspect ratio. Beginning in 1958 the Soviet Union had their own Sovscope 70, created when some traitor sold the secrets of Todd-AO to the Russians, which they in turn leant to Akira Kurosawa for his Russo-Japanese coproduction Dersu Uzala (1975). In West Germany there was Superpanorama 70, developed by Jan Jacobsen, a Norwegian in the employ of Munich-based Modern Cinema Systems (MCS), which apparently was sufficiently near in quality to Todd-AO that footage from both formats could be integrated in The Sound of Music. The Germans employed their wide-gauge system in much the same manner as the Americans: on period action-adventure pictures, stuff like The Black Tulip (1964), a swashbuckler starring Alain Delon, or Old Shatterhand (1964), an adaptation of one of German author Karl May’s wildly popular Western novels.

The same Jan Jacobson, who died in Augsberg in 1998, was also credited with building the first IMAX camera. The product of the Canadian IMAX Corporation, IMAX uses a 65mm negative, fed through the camera horizontally, as with Super Technirama, creating a frame area of unparalleled dimensions. The first IMAX theater, the Cinesphere, opened its doors in Toronto in May 1971. At much the same time, other pre-existing wide-gauge formats were being less and less in use at first-run theaters. The final film shot using the Todd-AO 65/70 process, The Last Valley, a drama set during the Thirty Years’ War written and directed by author-of-doorstop-sized-historical-fiction-tomes James Clavell, was released in January 1971. Since the beginning of the wide-gauge sensation there had been a profusion of blow-ups à la Doctor Zhivago, films shot on plain-old 35mm then printed on 70, with Otto Preminger’s The Cardinal (1963) one notable early example. These pseudo-70mm presentations, whose image quality might very well be impressive while still falling short of the genuine item, would continue to appear throughout the seventies—Waterloo (1970), The Towering Inferno (1974), The Wind and the Lion (1975), A Bridge Too Far (1977), and even Star Wars (1977), which played at the Odeon Marble Arch in London on a bowed D-150 screen—but for all practical purposes the cycle of shot-and-exhibited-in-wide-gauge films that began with Oklahoma! in 1955 had run its course by the end of the sixties.

4. Gauging the Present

After around 1970, the wide-gauge field was increasingly limited to special venue presentations of the sort that IMAX would gradually corner the market in. Traditionally, IMAX theaters were installed in cultural institutions—natural history museums and the like—and the subject matters of IMAX films overwhelmingly skewed toward exploring natural wonders of the world. The last I saw was the Canadian production Flight of the Butterflies (2012), tracking the migration of Monarch butterflies across the whole of the North American continent, filling the screen with fluttering orange and black. Some inroads have been made to push IMAX as a viable format for theatrical films, however, beginning with Walt Disney Productions’ millennial release of Fantasia 2000.

The wide-gauge torch has been, to a certain extent, kept burning by Disney, whose corporate parent company has long maintained an interest in unorthodox film formats—at the Epcot Center in Orlando, Florida, one can still experience immersive Circle-Vision 360°, a modern descendant of Cinéorama and Vitarama achieved through the simultaneous projection of nine 35mm images. Disney released Tron, shot partially in Super Panavision 70, in 1982; three years later The Black Cauldron (1985) would be the first Disney animated feature released in 70mm since 1959’s Sleeping Beauty. Pickings were slim through the following decade, limited to Ron Howard’s Far and Away (1992), Ron Fricke’s Baraka (1993), and Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet (1996), this author’s first 70mm experience, which he persists in remembering as awe-striking, regardless of the dizzying decline in Branagh’s critical reputation. Perhaps the most intriguing of the 70mm “revival” productions, at least as originally conceived, was the sophomore feature by Douglas Trumbull, Brainstorm. Trumbull had achieved a certain level of fame as one of the special effects supervisors on 2001: A Space Odyssey, but after his 1971 directorial debut Silent Running, he devoted an ever-greater amount of his time and attention to developing and fine-tuning a new 65mm wide-gauge process which he called Showscan. Brainstorm was intended to act as the unveiling of Showscan, the most distinguishing feature of which was its sixty frames-per-second frame rate, which was intended to create a surreal lucidity when used in Brainstorm, much as later films including Little Buddha (1993) and Shutter Island (2010) would use wide-gauge film in selected scenes to give the impression of a heightened hyper-reality. MGM, who held the purse strings on the troubled production of Brainstorm, finally forced Trumbull to use Super Panavision 70, though he has continued to experiment with high fps formats, also a preoccupation of Peter Jackson, who released a 48 fps version of The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012) in select cinemas.

Trumbull has kept a fairly low profile in recent years, though re-emerged to design the visual effects sequences in The Tree of Life (2011), one of several films that Terrence Malick and DP Emmanuel Lubezki have shot at least part of in Panavision System 65. (The others are The New World [2005] and To the Wonder [2012]). The System 65 camera, an update of Super Panavision 70 introduced shortly after the appearance of the wide-gauge Arri 765 in 1989, was also used on Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master (2012)—a curio in that it uses a format which has traditionally been reserved for large-scale costume epics for a rather intimate actors’ duet—and is a favorite of Christopher Nolan, an analog holdout like Anderson and Tarantino, who has filmed his movies from The Prestige (2006) to Interstellar (2014), in part or whole, in wide-film formats. The names listed above suggest that the wide-gauge, once beloved by studios and producers as a promotional tool, has been revived by name-above-the-title auteurs for either imagistic or status-symbol qualities—though this isn’t the whole story. Today as during the lean years of wide-gauge film, 65/70mm has sometimes been used in special effects sequences for the most dunderheaded of blockbusters—for example, on this year’s Jurassic World.

Taken altogether, this activity accounts for a small-but-not-unimpressive resurgence of wide-gauge as a creative option. It’s too soon to say if we’re in for a full-scale revival—and plenty of reasons to say that we’re probably not—but there has been an uptick in interest, even if nothing more than a blip, in large format cinema. This may in part be attributed to the same motives behind the post-Todd-AO wide-gauge boom: an attempt to decisively distinguish and elevate immersive cinematic spectacle from television and small devices—part and parcel with the “Go Big or Go Home” campaign currently being waged by the Regal Entertainment Group. Concomitant to this is a desire for any pretext to mark up prices for a Special Event spectacle, the same desire that briefly allowed the studios to believe that 3D was the savior of the box-office in the wake of Avatar (2009). The tactic is older than cinema: when Church displayed The Heart of the Andes at the Studio Building on West 10th Street in 1859, over 12,000 spectators paid 25 cents a head to view his masterpiece. Tickets for The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight were $1.00 in 1897, while orchestra level admission for a primetime screening of Oklahoma! at the Rivoli were $3.50—and who knows how much you’ll pay to see The Hateful Eight. As for the existence of a wide-gauge aesthetic, well, what could possibly unify The Tree of Life and Jurassic World (other than the presence of saurians, that is)? As ever, the canvas is worthless without the right artist to fill it, and all the resolution in the world means nothing if it isn’t clarifying something worth seeing.