Our True Intent Is All for Your Delight

By Nick Pinkerton

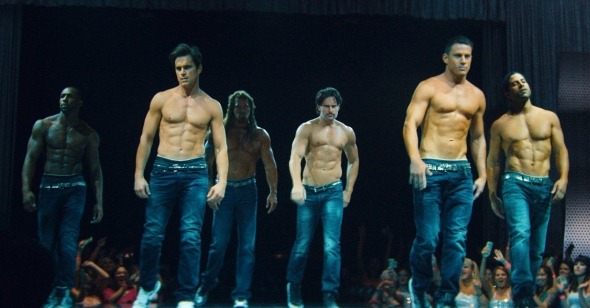

Magic Mike XXL

Dir. Gregory Jacobs, U.S., Warner Bros.

When last we saw Channing Tatum’s preternaturally talented male stripper Mike Lane at the end of Steven Soderbergh’s 2012 film Magic Mike, he had abdicated his G-string and walked away from the nightlife, determined try his luck at an adult relationship and to “put away childish things,” like Nick Nolte’s banged-up wideout Phil Elliott in North Dallas Forty tossing away the pigskin. The reference isn’t chosen out of the blue, for Magic Mike, with its social realist underpinnings, backstage exposé of a specific performance culture’s closely guarded secrets, and tincture of vague discontent, seemed no less than its gender-flipped companion piece, Soderbergh’s prior film, Haywire, to be mainlining 1970s American cinema—the vintage 1972-84 Warner Communications Company logo that appeared at the beginning of the film, as it does on the newly arrived sequel Magic Mike XXL, explicitly drives home the connection

Like most resolutions, Mike’s didn’t take. It’s hard to turn down a pile of sweaty untaxed bills in a night’s haul, and it’s especially hard to turn down a $167M+ return on a $7M investment, which is what Magic Mike pulled down by servicing the neglected female sector of the moviegoing population—and as it happens, servicing neglected women is what Magic Mike XXL is all about. As this go-around comes to a close, our hero is smiling on the boardwalk in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, the light of fireworks exploding over the surf reflected in his eyes, which have just a hint of crow’s feet. The outro jam accompanying the film’s final, celebratory montage, after Mike and (most of) his crewmates are coming off a rapturously received performance at a stripper’s convention, is DJ Khaled/Ludacris’s “All I Do Is Win,” though the title of another Luda track might best express the dominant theme of the Magic Mike diptych: “What’s Your Fantasy?”

While the name of Magic Mike XXL’s credited director, “Gregory Jacobs,” has a pseudonymous ring to it, all signs indicate that he in fact is a real person, an AD and producer who has worked extensively with Soderbergh since 1993’s King of the Hill. Assuming directorial duties on Magic Mike XXL, Jacobs is abetted by an incognito Soderbergh, the film’s editor and cinematographer. I don’t want to get into the question of whether this is a Howard Hawks/Christian Nyby-type setup, the Mike films share a very consistent visual style, beyond their obvious hallmarks: hot, ripped, glistening dudes, shot from angles meant to provide the most captivating possible vantages on their bumping and grinding. Without meaning for a moment to take anything away from the slippery choreography between camera and greased-up dancer, the moment that won me over to the first Magic Mike came before the razzle-dazzle started, a scene where Soderbergh’s documentary impulse was right out in front—the meet-not-so-cute between Mike and down-on-his-luck nineteen-year-old Adam (Alex Pettyfer), who’s taken a Craigslist construction job, as they’re laying down Spanish tile on a slapdash high-rise condo building in Tampa, one like the dozens we’ve seen Mike pass by on his way to work.

Pettyfer is gone from Magic Mike XXL, as is Matthew McConaughey’s sinewy, Naugahyde cowboy Dallas, the emcee and guru of the gang at the Xquisite Strip Club. As the movie opens, Mike is making a living with a custom-design furniture company—the exit plan that allowed him to step away from the game—but he’s single again, and doesn’t have any good excuse when the onetime Kings of Tampa come calling to draw him out for one last ride up the coast to Myrtle. Like the first film, XXL is full of lucid, deep-focus wide shots grounding the characters in their environment, a real world of bills and invoices, and a real southeast of strip malls, strip clubs, and convenience stores. (The latter is the scene of the movie’s most gut-busting set-piece, in which Joe Manganiello’s Big Dick Richie takes a dare to make the sour-faced female clerk smile with an impromptu strip tease set to Backstreet Boys’ “I Want It That Way.”)

Stuffed between the cracks of Magic Mike’s tale of stuffing between cracks was a picture of life in post-economic-collapse America, a fact that didn’t escape notice by commentators who require some redeeming social value to validate sensory pleasures. The spur of hustle is less sharply felt in XXL, a film that offers little in the way of penitent justification for its indulgences, though for those looking for one might I suggest: a commentary on contemporary American life as a state of constantly rankling low-level dissatisfaction brought on by impossible (yet constantly reinforced) expectations, ameliorated only by periodic escape into custom-tailored fantasy, in which we are all the glassy-eyed convenience store clerk listlessly fingering our smart phone, a bored and horny public waiting to be lap-danced back into a semblance of life.

Magic Mike XXL is able to express something about catering to fantasy life with such clarity because it deals with the business of female fantasy—or, rather, the prepackaged version of female fantasy filtered through available cultural signs and symbols and enacted in the arena of the strip club. (More or less explicit references are made to Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey in the climactic orgy of the ecdysiasts’ art.) The industry of ego-stoking male fantasy wouldn’t register in the same way—it’s the very air we breathe, and we often fail to identify it as such—though male fantasy also plays a role in XXL, as the boys, inspired to enliven their tired routines in a molly-fueled brainstorm, incorporate their own impossible dreams of professional agency into their act. The film establishes its “reverse the gaze” agenda early, in a scene where Mike, alone in his workshop, feels the siren call of the stage, unconsciously grinding in time to “Pony,” formerly Magic Mike’s signature song, his welder’s mask evoking memories of Jennifer Beals in Flashdance. It’s a wowing, reeling solo number, proof if any more should be needed that Tatum is the Ginuwine article. Absurdly, in Terrence Rafferty’s recent piece for The Atlantic proscribing “The Decline of the American Actor” and bemoaning the plight of the under-40 set, 35-year-old Tatum is mentioned only in reference to his role in last year’s Foxcatcher, which gives the game away as to what kind of acting Rafferty thinks is worth talking about. (Hint: It’s the type that Michael Fassbender will be doing right, left, and center in Steve Jobs.)

Unlike a great many actors who had to bulk up when the industry devoted itself to superhero movies, Tatum—set to star as X-Man Gambit in fall 2016, and the “Duke” of two G.I. Joe films—looked the part from the get-go, a big, solid ex-high school jock who found his way into acting via backup dancing and modeling, with a few interesting detours along the way. It is curious, then, that he has rarely achieved more than adequate functionality in straight action roles—I watched the likes of The Eagle and White House Down, and I would be very hard-pressed to tell you anything about either. Instead, Tatum has distinguished himself in musicals (the first two chapters of the Step Up dance franchise), comedies (Lord and Miller’s Jump Street movies), and films that offered a bit of both (Magic Mike). The last was preceded by the public revelation, in 2009, that Tatum had done time as a stripper under the pseudonym “Chan Crawford,” a bit of autobiography that he would rework into a fictional framework with Soderbergh and screenwriter/production partner Reid Carolin. It was his 8 Mile, his Get Rich or Die Tryin’, his To Hell and Back—and how many actors in 2015 even seem to have a backstory?

As sure as every comedian must long to stretch his range and petition an audience for tears, there comes a time when every musclehead actor has to try his hand at comedy, usually being effeminized for humorous incongruity—the same novelty that comes of having ex-linebackers on Dancing with the Stars. (A cameo by Michael Strahan in Magic Mike XXL touches on this.) Tatum, however, is never more out-of-place than when he’s obligated to lug around a machine gun—but rippling his torso in XXL, he’s right at home. As demonstrated in scenes with somewhat obligatory love interest Amber Heard, Tatum’s a wonderful flirt, possessed of the kind of abashed stammer associated with flimsier fellows like Woody Allen or Hugh Grant, and able to give line readings that have the effect of seeming ad-libbed whether or not they in fact are. (To Jenna Dewan in the first Step Up, as she lures him out to an abandoned section of Baltimore waterfront: “Is this where you kill me?”) He can also kick it around with the boys, which XXL gives him ample opportunity to do—it’s hard to remember the last time a hang-out movie this pure came around, one that felt like it really had time to breathe, rather than the punctiliously scheduled, strained banter of Age of Ultron, penciled in between fireballs.

The group dynamics are one of Magic Mike XXL’s inducements; the other is the dance, which a straight man would have to be a quivering column of gay panic not to get a kick out of—if the washboard abs don’t make you “Woo,” you can always bask in the pure spectacle. With respect to the final floorshow, the centerpiece of the film is a visit to a high-end, member’s only strip club in Savannah with a mostly black clientele, where Mike tries to inveigle an old flame and expert emcee, Rome (Jada Pinkett Smith), to come up to Myrtle with them. There Mike and company take in the show, including a performance by a freestyle troubadour, Andre (Donald Glover), and a hip-hop dancer (Stephen “tWitch” Boss) whose style is the spitting image of Mike’s.

You think for a moment that there’s a showdown in the works, but here is where Magic Mike XXL distinguishes itself—competition has scarcely any place at all in its world, and problems aren’t solved so much as dissolved. As soon as Ken (Matt Bomer), the crooner of Mike’s group, is alone with Andre, he’s all earnest professional admiration, picking his brain for advice. Mike doesn’t try to embarrass or outdo his doppelganger—although, at Rome’s request, Mike does pop off a zero gravity solo dance that ends with him greedily seizing women from the audience and stacking them atop one another, like a hoarding, humping monster. The stylistic soulmates instead take advantage of their symmetry, arranging a mirror-image ebony-ivory routine together. One of the only major obstacles to be overcome in the film is Big Dick Richie’s search to find a woman who can accommodate his big dick. (SPOILER: He does.) There’s no bad-guy crew, of the kind you might find in a Step Up film, no opponents to be dusted at all. In fact, when Mike and the boys are out on the boardwalk together, flushed with the joy of performance, I couldn’t remember if they’d won the competition, or if there ever was a competition to begin with. They’ve lived to dance another day—and isn’t that enough?